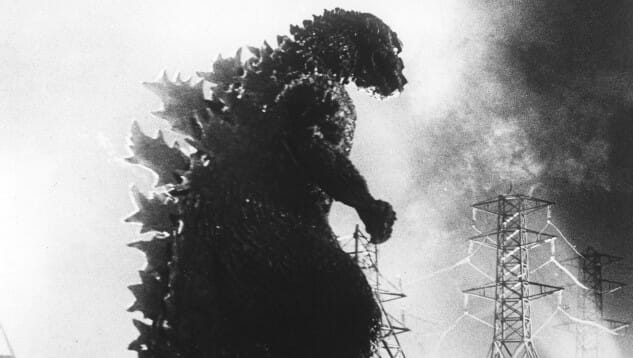

The Best Horror Movie of 1954: Godzilla

This post is part of Paste’s Century of Terror project, a countdown of the 100 best horror films of the last 100 years, culminating on Halloween. You can see the full list in the master document, which will collect each year’s individual film entry as it is posted.

The Year

The intermingling of horror and science fiction cinema is in full swing here in 1954, as the two genres combine to create some of the features we think of as being most indelibly tied to the imagery of “1950s monster movies.” The most prominent and long-lasting in its appeal and impact is of course Godzilla, given that it’s been receiving sequels for more than 65 years now, including 2019’s King of the Monsters. It’s hard to overstate what a persistent and foundational presence Godzilla has been in both Japanese and American pop culture, informing on some level every other representation of giant monsters in the years that followed.

In the moment, however, there’s little doubt that in the American market, the most immediately influential horror film of the year was Them! This tale of radioactive, giant ants laid the foundation for so many of the “big bug” and “radioactive monster” films that quickly followed that it was practically a complete template for every subsequent offering, from The Deadly Mantis to The Black Scorpion, The Giant Gila Monster and Empire of the Ants. These films weren’t exactly delicate in their nuclear age paranoia, and were less than scientific in their depiction of the effect of radiation on living tissue, but when you really get down to it, there’s nothing here any less realistic than the content of comparable, modern B movies like Birdemic or Geostorm. In any era, there will be audience members who would prefer to be titillated by the fantastically anthropomorphized worst case scenarios of current pop cultural fears, like giant monsters, rather than grapple with the reality of how things like nuclear proliferation or climate change might genuinely mean mankind’s destruction. In 1954, it was simply easier to dismiss a giant ant puppet than it was to dismiss the reality of Kruschev amassing an ever-growing nuclear arsenal. As ever, movies represented a brief respite from such harsh truths.

Other notables from 1954 include Alfred Hitchcock’s relentlessly entertaining, single-location thriller Rear Window, which is certainly horror adjacent but difficult to give the top spot in any kind of proper horror count-down; Gog, which set plenty of the tropes for future “killer robots on the loose” movies such as Chopping Mall; and Creature From the Black Lagoon, the oft-forgotten last proper entry in the original Universal Monsters cycle, filmed in 3D but largely presented in 2D thanks to the gimmick’s popularity fading into obscurity relatively quickly. Although the titular Creature, also referred to as “Gill-Man,” is typically counted among the earlier Universal Monsters, the film itself feels like something of an outlier—a would-be science fiction horror film with hints of an ecological message, hampered by dated tone and structure that feel straight out of the early 1940s. Thanks to the sight of the radiant Julie Adams in her iconic white bathing suit, though, the film has managed to retain a certain vivid place in the collective memories of those who came of age in the 1950s.

1954 Honorable Mentions: Rear Window, Them!, Creature From the Black Lagoon, Gog, Target Earth, The Witch