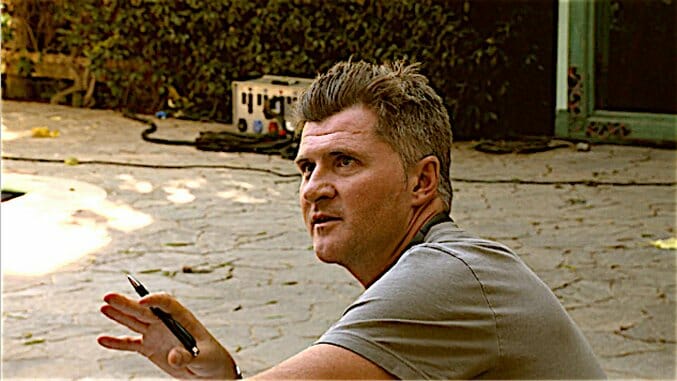

Jamie Marshall has spent a heck of a long time building up to his directorial debut. He started out growing up as the son of legendary British film producer Alan Marshall, whose filmography includes films like Midnight Express, Pink Floyd: The Wall, Birdy, Angel Heart, and Starship Troopers. It was quite a childhood.

“I was very fortunate growing up in the business,” Marshall recalls. “I think it was the first time I kind of knew my dad did something a little bit offbeat, so to speak. We went to Turkey when my dad did a film in 1978 called Midnight Express and I was an extra in the film. And like the attention of hair, make-up, and wardrobe—even though, obviously I was just in the background, I was part of a family visiting the prison. That was the first time I was like ‘Okay, my dad does something pretty cool.’”

It got even better.

“Two years later,” Marshall continues, “he did Pink Floyd: The Wall, and I did the same thing. I was a skinhead. They shaved my hair, you know, they put me in the Doc Martens and put me in the audience. And then I was like ‘Okay, now I really know my dad does something cool.’ Looking back to it, when I tell friends the story they’re like ‘You don’t know how lucky you were.’ I was blessed. It was just—it was really cool; you know?”

Now the producer’s son has directed his first film, a small budget thriller called Dirty Lies. “Coming up with the idea,” he recalls, “and then thinking through the execution, it’s like, ‘Okay, well 80% of the film has got to take place in the house, because we’ve only got one. And then I have to build the story around budget, and then hopefully put some of my personal stories in from when I first started off in Hollywood. I put some of those stories into the lead character, what I did and what my friends did too, to get ahead when working on production or working for producers. Then I tried to create a true story of the crime. In this case, we just came up with the idea of stealing the necklace, but the film was obviously more about how the four roommates at the beginning were all doing pretty good. They all live in a pretty nice house. And then one night, how everything changes. Their true selves come out.”

It’s hardly surprising that the thriller he set out to make was a thinking man’s thriller, a film that tried something different from the average film. Because Marshall has learned from the best, beginning but not ending with his father. In between those childhood cameos and this directorial debut, he worked on over forty films, including films with some legendary directors. He began as a Second Assistant Director on Showgirls, and hasn’t stopped since. (His most recent gig working with Martin Campbell on his forthcoming film The Foreigner.) Along the way, he learned a ton, and he agreed to share some of the wisdom passed down to him by filmmakers like Antoine Fuqua, Scott Cooper, Gavin O’Connor, Martin Campbell, John Woo, Terry Gilliam, Catherine Hardwicke, and his father Alan Marshall.

Paste Magazine: There’s no bad place to start with all the people you’ve worked with, but why don’t we start with Antoine Fuqua?

Jamie Marshall: Antoine is just a remarkable storyteller. He was the first one that gave me second unit, and it was a big second unit. And what I really learned from Antoine was camera lenses. We would have conversations about lenses, and it was a whole new ballgame. It wasn’t just, “Oh, shoot it on the 27 then punch it.” It was like, “No, use the lenses to really help tell the story.” He’s a remarkable shooter. He would say, “If you’re doing that left-to-right movement, keep the camera going, even if it’s a slow crawl. Keep the camera alive.” And storyboarding, relentlessly. I sat with him, and I learned a lot. The opportunity he gave me was incredible, by trusting me. We’re still very good friends.

Paste: Stereotypically, the danger of storyboarding too much and planning out the camera movements too much is that the performances can feel unnatural or stilted. And yet he is a director where those performances do not feel that way. Do you have any sense of how he’s able to have the shots be so planned out and yet also allow enough room to some umph from the actors?

Marshall: Well, Antoine is a natural. There are a lot of directors—especially in television—who map out where they’re going to put the cameras and lose something, but with Antoine, a lot of it comes from within. Antoine will make the crew really nervous—like, he’ll have the actors come on the set, and he might rehearse them four or five hours for a 12-hour day. And everyone’s like, “Oh my god, we haven’t even shot anything yet.” But I think it’s his commercial experience. Once he sees that whole thing come alive, it’s “Bam, bam, bam.” He’s cut the scene in his head, and he knows exactly what he wants for each part of the scene.

Paste: Right.

Marshall: But the more freedom you can give the actors the better I think the film will be. That was a huge learning lesson for me, that started with Antoine and then I also learned that from Gavin O’Connor and Scott Cooper. Just like, being on set with them and having them tell me, “If the actor’s going to go completely go off script, I want to make sure that that’s good, you know?” And the scene comes that much more alive because you’ve given them that freedom.

Paste: Especially, in the case of Scott Cooper, when the actor you’re giving that freedom to is Christian Bale.

Marshall: Yeah, I—I’ve got a good Christian Bale story. I did Out of the Furnace with Scott Cooper. I was an executive producer and AD on that film, and Christian, when he first came to Pittsburgh, I went to see him in, the day he arrived. And eventually he just showed up with like—like a shoulder bag, you know? He’d shown up to Pittsburgh to be a steel worker. A couple of pairs of jeans and a couple of t-shirts, and he was being in character. We said, “We’ll take you into some of the neighborhoods where we’ll be shooting,” and he’s like, “Oh, I’ve already been there.” He’d been in town two or three weeks. We were there in Pittsburgh to film, and we didn’t even know. He’d actually flown on his own and was just wandering around the streets.

Paste: Wow.

Marshall: That, to me, is like a whole different type of actor that takes that on himself, to go to the neighborhood. He’s like, “No, I didn’t want to do it the day before shooting, I wanted to—I really want to get into it, and understand the neighborhood and the feel and the vibe.”

Paste: That’s fantastic. Well, while we’re on Scott Cooper, why don’t you tell me something else you learned from Scott Cooper?

Marshall: I always think of Scott and Gavin similarly. Scott, from a production point of view, he was a genius. If we were ever in trouble, he’d say, “I’m the writer-director, I’m in charge of the script, don’t worry.” And I was like, “Whoa.” I’d just worked on movies, without writer-directors, and it was all about delivering a studio a script report—how many pages you shot, what you shot, etc. But when you’re the writer, you have that control of the script, and Scott, a couple of times when we were shooting, would say, “You know, we don’t need to do that scene; we’ve got what I need to make it work.” He’s a great guy, and being an actor himself, his rehearsal process is very neat. He wanted that freedom for the actors. He was really an open director to ideas coming from department heads and the cast to make the best movie he could. And very confident, which is another great trait to have, because confidence shows your leadership.

Paste: Yeah.

Marshall: I’ve worked with directors that aren’t confident. Being an AD in that circumstance, you literally have to take over that confidence role and put it out there so everybody knows that you’ve got some type of leadership on the set. But with some directors, like Martin Campbell with whom I’ve worked for 16 or 17 years, you’re literally holding on, trying to keep up with him because he’s a machine. There are some directors, you’ve got to nudge along. Whereas with Martin, you’ve got to hang on.

Paste: How about John Woo?

Marshall: John actually gave me my first directing job. I don’t really mention it ever, but I got to direct second unit at the end of Face/Off. It was really funny because they named me first AD of this little unit, but the little unit ended up shooting scenes with actors and everything. And in the end, Paramount said because I was shooting on stage and John wasn’t there, I had to be named the unit director. So that was the first time I got a taste of directing.

Paste: Nice.

Marshall: They even gave me a chair! And I was like, “This is good.” I was going to work in shorts and a t-shirt, and then I was like, “No way, I’m putting the pants on, the leather jacket, because I’m the director now.” I was a bit of a kid, and he trusted me and you know, I got to direct John Travolta and Nic Cage! It wasn’t like they were doing constructed scenes. They were more like pick-up shots, but John was directing next door, and we had to be done by Christmas. I got, I think it was two and half, three weeks of directing, and I was like, “Okay, I’m a director now.” But of course, I learnt the hard way, you know? But one thing I can tell you I learned from John. His English wasn’t great but the language of film is how you communicate and you don’t really need to be totally proficient with English. And John would like, now and again, kick me on the ass, like give me a little shot, and that was his way of saying “Hurry up, Jamie, get going,” you know? And, you know – again, I was a lot younger but watching how he orchestrated camera moves. I mean, we did this huge shoot out one night on Face Off and John had like six cameras and he had two steady-cams going, dancing around the room. What a filmmaker. Not one camera ever got in the way of the other.

Paste: Wow. That’s great (laughs). That’s awesome. And how about Terry Gilliam. Tell me about something you learned from him.

Marshall: I think the biggest thing I learned from Terry is don’t ever be afraid to ask for anything. I remember one day on Fear and Loathing, he said, “I want to get some little people today.” And we’re like, “Oh, no problem. We can—we’ll rush and call some little people.” And he said, “Yeah, but we need them to be trapeze artists.” Everyone just looked at each other, because with Terry you never know if he’s joking or not. “Are you joking, Terry?” “No.” So of course we found them. That was Terry being Terry, you know? So, just don’t be afraid to ask. And Terry is one of those people who, literally, if he’s going to ask an actor to do something, he’ll do it as well. If it means you’re going to take your clothes off and run through a dessert or something, Terry will be like, “Okay, this is how you do it.” And he seems to be able to do everything with a smile, and keep it positive and confident—and throw in a little crazy.

Paste: Before we go, I do want to ask you about working with Catherine Hardwicke, and what you learned from her.

Marshall: Catherine, I love a lot. Catherine is my girlfriend, too …

Paste: Yes. So you better be very careful in how you answer this question.

Marshall: Yeah,! She’s my biggest fan. The one that’s saying, “You’ve got to keep pushing, you’ve got to keep trying.” Because that’s what she’s been doing her whole directing career. I did the film Twilight with Catherine, and it was kind of unique because I was there right at the beginning. I was on Twilight from the get-go, when we were making a modest little budgeted vampire movie that turned into a best-selling book phenomenon. And I think one thing I learned from Catherine, that I continue to learn from her, is casting. Her unique casting process, finding talent. The amount of times I had to literally vacate the premises because she turned her house into the proposed set. And this is even before the actors have the role—this is in the reading process. She really tests them to the limit, and she actually has them do a lot of the moving. And as a screenwriter she’s learning so much about what is working, and what isn’t working. Then you can go back and adapt the script because you’re learning it in the casting process.

Paste: Through the casting process—that’s brilliant.

Marshall: Yeah. And it’s such a simple little trick, that, you know I think everybody could do. She says, “These actors want acting. Don’t just give them five minutes in a room.” So it’s been a great partnership

Paste: Well, normally that would be a place that would be a perfect place to end. But I think the place that I really need to end is by asking you this. I’m sure it’s hard to narrow it down to just a couple of things, but tell me about a couple of things that you’ve learned from Alan Marshall.

Marshall: Wow. (long pause) Patience, you know? Patience is a big one. And the importance of family.

Paste: Yeah.

Marshall: And being brave. When I told him that I was going to sell my house and make a film, some parents might have said, “You know, I don’t think that’s a good idea.” But he was just like, “Go for it. This is the way you’re going to learn.” So that’s really it in a nutshell. He was always patient and confident in me. And I think I turned out okay. (both laugh)