Whenever an older, revered icon of the film industry dies, there are plenty of testimonials and remembrances written about that person. But it’s sad that we only take the time to fully appreciate these people’s brilliance after their passing. Hence, The Greats, a recurring column that celebrates cinema’s living legends.

Director Martin Scorsese has been making movies at such a level of acclaim and accomplishment for so long that he’s become a fixture of American cinema, his backstory as familiar as the plots of his best-known films. Growing up with asthma in Little Italy in New York, he had to stay inside, gorging on movies and observing the low-level criminals who roamed his neighborhood. Like Peter Parker getting bitten by a radioactive spider or Bruce Wayne watching his parents’ murder, these facts in Scorsese’s biography are iconic and oft-mentioned, suggesting the humble origins from which a filmmaking superhero emerged.

Just as Scorsese’s upbringing is now engrained in viewers’ minds, so too is the accepted canon of his greatest work: Mean Streets, Taxi Driver, Raging Bull, Goodfellas. But the downside of beatifying a filmmaker is that it risks reducing him to imposing totems, unfairly diminishing his other movies in the process because they’re not perceived to be masterpieces. But if Scorsese deserves to be heralded for his finest achievements, his less-celebrated feat is his ability to produce a series of fantastic other movies—near-masterpieces, if you will—that would be impressive by anyone else’s standards. Some of them are so good, in fact, that you may actually prefer them to the accepted canon.

But first, some quick biography. Born Martin Charles Scorsese in November 1942, he was raised Catholic and even considered the priesthood. But he found a different, although somewhat similar calling in the movies. “[T]he ritual of going to the movies with your father … became important to me,” he told Richard Schickel for the critic’s 2011 book Conversations With Scorsese. “There was a sense of peace [in a movie theater]…. You had faith when you went into the church. And you had faith when you went into the movie theater, too. Some films hit you more strongly than others, but you always had that faith. You’re taken on a trip, you’re taken on a journey.” Hearing Scorsese talk about movies, even to this day, makes them sound like transcendent, almost religious experiences. Few contemporary filmmakers have translated that passion into so many euphoric cinematic moments.

After going to film school, Scorsese began directing his own pictures. 1967’s Who’s That Knocking at My Door and 1972’s Boxcar Bertha were his first features, but it was his third film, Mean Streets, that helped establish his reputation as a director of movies about men consumed by inner demons, often resorting to violence as a means of expression. Littered with rock and girl-group R&B songs on the soundtrack, Mean Streets first popularized his tendency to use pop tunes as the sonic background for his films, a technique that would be incorporated by disciples like Paul Thomas Anderson, Quentin Tarantino and David O. Russell.

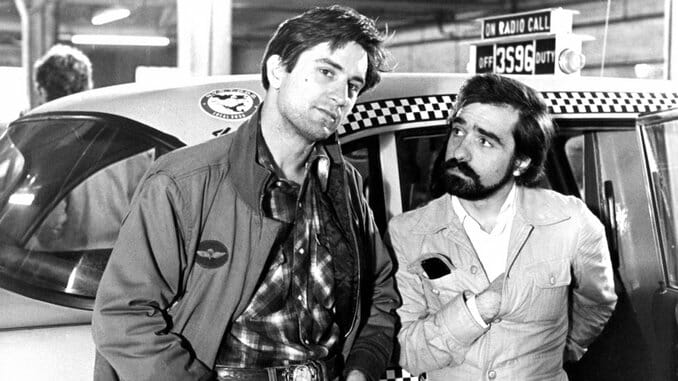

His next movie, Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, was his first to win an Oscar, for Ellen Burstyn for Best Actress, and the film later got spun-off into the TV series Alice. (Scorsese is one of two terrific directors who saw one of their ’70s movies adapted into a sitcom, the other being Robert Altman’s M*A*S*H.) But Taxi Driver was the breakthrough: a seething condemnation of alienation—not to mention New York’s descent in the 1970s into a crime-ridden hellscape—delivered with such clinical coldness that when Scorsese’s star (and longtime collaborator) Robert De Niro finally explodes, it’s unspeakably upsetting. If Taxi Driver now feels slightly overrated, it’s only because the movie’s DNA has crept into so many subsequent filmmakers’ efforts. Scorsese grew up loving Westerns, and Taxi Driver could be his version of The Searchers—except his man-out-of-time ends up not redeeming himself, continuing to patrol the dirty streets he loathes.

You don’t need to be reminded that Mean Streets and Taxi Driver are seminal films. But you may want to reconsider the movie Scorsese filmed just nine months after the release of Taxi Driver. If that film’s Travis Bickle was the manifestation of humanity’s darkest elements—its longing and violence and misanthropy—The Last Waltz was a triumphant, melancholy celebration of our best selves. Chronicling the Band—Bob Dylan’s onetime backing band, which had become an acclaimed act in its own right—during a farewell concert in San Francisco, The Last Waltz is Scorsese’s purest salute to the classic rock of his youth. It’s also probably his warmest film, exploring artistry and the passing of time through behind-the-scenes interviews with the Band and ebullient onstage performances with the group and special guests like Eric Clapton, Van Morrison and Neil Young. (The movie radiates such a formidable high that even Neil Diamond slays.) Scorsese’s ’70s cinema was filled with pain; The Last Waltz was a moving antidote, suggesting that even when some things come to an end, their lingering value remains.

Even more so than Taxi Driver, 1980’s Raging Bull was an anguished cry from its maker. Reteaming with De Niro, who believed in the merits of a story about former boxer Jake LaMotta long before Scorsese did, Raging Bull is a film about emotional torture—the abuse we put ourselves through, both physical and mental, because we aren’t capable of behaving any other way. Outside of Robert Rossen’s 1947 film Body and Soul, which inspired Raging Bull’s fight scenes, it’s the greatest boxing movie ever, which is impressive considering how uninterested Scorsese is in sports. “My father’s a big fight fan but I don’t know anything about boxing and I wasn’t interested in films about boxing,” he told Roger Ebert. But when Scorsese started internalizing LaMotta’s struggles, drawing on his own battles with drugs in the late ’70s, Raging Bull made sense to him. De Niro won an Oscar, but the film (and its director) got beat out by Robert Redford’s Ordinary People, and for a while that seemed to be Scorsese’s legacy: making soul-crushingly powerful movies that would end up losing to popular actors’ comparably lightweight dramas. (This phenomenon would repeat itself 10 years later with his Goodfellas being bested by Kevin Costner’s Dances With Wolves.)

Scorsese’s ’80s don’t get as much attention in his oeuvre—or, more accurately, the wrong things get magnified. He directed the video for Michael Jackson’s “Bad.” He made The Color of Money, one of 1986’s biggest hits. (It also landed Paul Newman his only Oscar.) But that overlooks his caustic examination of celebrity, The King of Comedy, his dark comedy-thriller, After Hours, and his excellent short film, Life Lessons, from the otherwise negligible omnibus, New York Stories. And as far as passion projects go, The Last Temptation of Christ remains stirring, an imperfect attempt to make Jesus (Willem Dafoe) a real, flawed man. Some of its effects haven’t aged well, but Christ is a benchmark for how a filmmaker should properly exorcise his greatest obsessions: the limits of masculinity, the search for meaning in the world, the struggles to overcome Catholic guilt. Despite its flaws, it’s an exhaustingly personal drama—you feel its creator wrestling with every frame.

Goodfellas is an indisputably bravura film, but its glowing critical assessment has overshadowed its supposed companion piece, Casino, which is even more ambitious. (And as a corrective to this great filmmaker’s one looming flaw, Casino features one of Scorsese’s few truly fleshed-out female characters in Sharon Stone’s ferocious Ginger.) In the ’90s, Scorsese kept pushing himself, going for period romantic drama in The Age of Innocence and diving into psychological horror with Cape Fear. Kundun was a sincere attempt at a biopic of the Dalai Lama. But maybe his most underrated movie of the period, like Casino, was dismissed because it seemed like an echo of an earlier masterpiece. Bringing Out the Dead was Taxi Driver in the world of paramedics, but it’s a more ghostly and surreal film, Nicolas Cage giving one of best latter-day performances as a man beginning to crack from the life-or-death stakes of his job. The film focuses on one of Scorsese’s enduring themes—a man in spiritual torment—but is rendered with new maturity and the same old spark.

Since then, Scorsese has seemed to ease into the role of an elder statesman, a living filmmaking legend. Gangs of New York and The Aviator were sniffed at by some, who accused him of compromising his artistic integrity to make measly “prestige” epics. But while those films are a bit bloated, they’re also dark portraits of the American Dream gone screwy, particularly The Aviator’s cautionary tale of Howard Hughes, whose demons were no less fiery than those of Bickle. And they also began Scorsese’s relationship with Leonardo DiCaprio, the director’s most fruitful since his pairings with De Niro.

There are those who will never accept DiCaprio as a major actor, who will permanently see him as the pinup of his early years. These people are simply denying themselves the pleasure of experiencing how DiCaprio has energized Scorsese’s recent films, delivering some of his finest performances in the process. DiCaprio’s work in The Aviator showed an intensity that would soon be topped by his work in Shutter Island, this critic’s pick for DiCaprio’s and Scorsese’s best movie of the new century. A beautifully nightmarish horror movie that’s really a finely wrought character piece, Shutter Island is perhaps the quintessential off-canon Scorsese work, a film that isn’t immediately accepted as a masterpiece but is so rich and evocative that it’ll knock any unsuspecting viewer on his ass. At the time of its release, Shutter Island was largely admired but unloved by critics. There was so much attention given to the film’s “twist” that there was an assumption that Shutter Island was merely an M. Night Shyamalan-style puzzle movie. Subsequent viewings reveal how little importance the “twist” of the story is: Rather, it’s Scorsese’s portrait (and DiCaprio’s portrayal) of a haunted cop who investigates a disappearance but ends up investigating himself that resonates. Scorsese has always littered his movies with references to the cinematic past; with its articulation of a deranged mind and its obsession with dead and/or missing former lovers, Shutter Island aspires to the doomed grandeur of Vertigo. The film holds its own with Hitchcock’s classic.

There are movies that haven’t even been mentioned that might be your own favorites: The Departed (which finally won him that Oscar that never mattered anyway), Hugo, New York, New York, his early experimental short The Big Shave. And that’s the point. Who needs a canon when there are so many gems lying in wait? In 2000, Esquire polled different film critics to answer the question, “Who will be the next Martin Scorsese?” Paul Thomas Anderson, Alexander Payne and David O. Russell were all cited. (Scorsese’s own vote went to Wes Anderson.) All fine choices. But the question suggests that we need a “next” Scorsese because the old one is all used up. Far, far from it. If anything, he’s ripe for rediscovery.

Tim Grierson is chief film critic for Paste. You can follow him on Twitter.