How do you nurture a child, and how do you encourage an artist? Microbe & Gasoline is a film that offers up a somewhat terrifying answer (for parents, at least) to both questions: freedom. In theory, it’s a bad idea to let your child build a “car” with his buddy, and take that car out on the open road for the adventure of a lifetime. But like so many other iconic films about childhood adventures (Moonrise Kingdom, Ferris Beuller’s Day Off), Michel Gondry’s latest insists that the life of a child, especially a budding artist, is incomplete without those dangers parents are so often told to fear—those adventures kids must so often have behind our backs.

Microbe & Gasoline is a portrait of the artists as young men, as complex as a James Joyce novel, and as delightful as Gondry’s other achievements, including Be Kind Rewind and Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind. And even while treading in familiar waters with its overarching plot, this beautiful film accomplishes what seldom few stories can by presenting a tale of youth and friendship and amplifying simple themes so that the result is a powerful treatise on art, creation, intellect and genius.

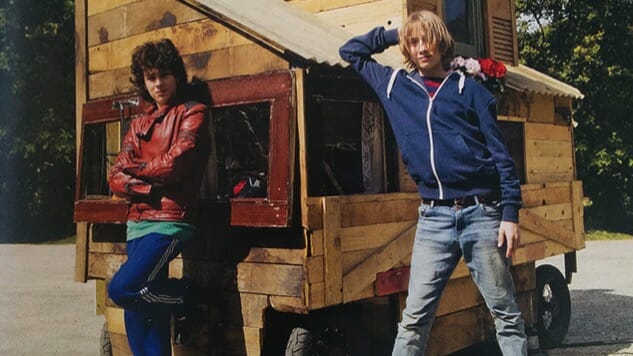

Gondry’s story poses first as one focused on childhood bullies and classroom outcasts. Ange Dargent plays Daniel (dubbed “Microbe” by his fellow classmates for his minuscule build), the kind of kid talented enough to get his own small gallery showing, but from a family where there are enough distractions that nobody bothers to go see it. He begins finding solace in the new kid at school, Théo (played by Théophile Baquet), who’s good with his hands, rocks a leather jacket, rides a motorbike and is so adept at building and fixing things that he’s granted the nickname “Gasoline.” In Théo, Daniel finds his first true friend, creative partner and collaborator: the first person to support (and challenge) his art.

Microbe & Gasoline steps into grander territory when it uses this friendship as vessel to pose bigger questions: “Are you easily influenced, and does this make you less of an artist?” or “How do you know if you’re a creative genius, or just often in the company of one—the friend of the great one, but not so great yourself?” According to our two adolescent heroes, it’s never too early to start asking. And their interactions, performed beautifully by Dargent and Baquet, work to negate the commonly held and reinforced belief that young people are immature and frivolous. Even as Daniel and Théo are true to their age—not above fart jokes and obsessed with their appearances (the film embraces all this)—these characters are presented through a lens and a narrative that is sincerely interested in their art and intellect, their pain and their pleasures.

As the school year ends, the story transitions to a prototypical but still distinctive adventure, one less concerned with the families and educational environments that often seem determined to destroy those young thinkers who our societies (from France, where the film is set, to our own America) need. Daniel and Théo build a hilariously charming, very small, makeshift mobile home, lie to their parents (as all creatives must often do), and set out on the open road. Of course, they both have completely different end games in mind—one seeks young love, while the other hopes to relive former pleasures achieved at an old summer camp. But Théo, the more bodacious of the duo, perfectly sums up their overall plan: “Goodbye shame! Let’s kick the future’s ass.” It’s such a noble quest—what could go wrong?

One way to judge a film, or any other genre of story, is to consider the effects when the inevitable occurs. When you know it’s safe to assume that everything will go wrong, that the makeshift mobile home isn’t strong enough to survive an epic adventure, that the relationship will be adversely affected, but a reunion of some sort will eventually come about—are you still excited to watch it all unfold? Is the dialogue smart enough, and are the characters believable and fascinating enough to make the inevitable worthwhile? In the case of this film, yes. And there’s a parallel here to the Eternal Sunshine quandary: If you hold in your hands proof that you and the girl you like won’t make it, is it still worth a try? Some stories are so good that the outcome is rendered almost irrelevant. The how becomes infinitely more compelling than the what.

Perhaps the film’s only disappointing factor is how it handles its minor characters. Fans of the wonderful Audrey Tautou will be surprised to see her reduced to “The Mom.” While she is offered some nuance, she’s an afterthought to the greater story, even somewhat of a nuisance. It’s fair treatment in some ways, as the film is critical of parental figures, but one wishes she could have contributed more.

Taking full advantage of its two young protagonists and all that they offer up in the way of drama and comedy, Microbe & Gasoline celebrates the notion that there’s a thin line between genius and idiocy. And then it walks that line itself, teetering between the eye-roll-inducing absurd and the Derridean-like theoretical world which a certain kind of youth inhabit. Unafraid to wade in the shallows or dive into the deep, Gondry’s tale sends a clear message to both the young and old: Creation is the purest act of rebellion. If you have it in you to create, you must—and if you’ve been robbed of such a gift along the way, there’s nothing like an adventure (preferably with minimal planning) to get it back.

Director: Michel Gondry

Writer: Michel Gondry

Stars: Ange Dargent, Théophile Baquet, Audrey Tautou

Release Date: July 1, 2016

Shannon M. Houston is a Staff Writer and the TV Editor for Paste. This New York-based writer probably has more babies than you, but that’s okay; you can still be friends. She welcomes almost all follows on Twitter.