Note: Suicide is an inherent part of a discussion about Sonatine.

Takeshi Kitano is something like the Clint Eastwood of Japan: Multi-talented, renowned in front of and behind the camera, and with a career outside film that includes several intriguing asterisks (for Clint, a stint as mayor; for Kitano, a video game he designed specifically to antagonize the player and indeed even the idea of video games).

It’s entirely understandable why Quentin Tarantino, the world’s most overenthusiastic cinephile, would use his newfound clout with Miramax to distribute one of Kitano’s signature early films under Tarantino’s short-lived Rolling Thunder Pictures label. Kitano’s fourth film, 1993’s Sonatine, will remind the American viewer (and the ’90s-’00s, post-Tarantino action film connoisseur) a lot about Tarantino’s particular oeuvre, with its talky gangsters, sudden violence, and palpable sense of style. As it turns 25 and we continue in the midst of a… Tarantinaissance? … that has seen the director’s pace step up significantly in the last several years, it’s worth taking a look back at one of the bedrock features of the yakuza genre that so clearly has inspired him.

If you’re expecting a Tarantino-style romp with Sonatine, you should know you’ll be disappointed—or perhaps in for an unexpected experience. Kitano, who wrote, directed and stars as the main character, provides us with some of the same touchstones and scenarios as Reservoir Dogs or Kill Bill, but the intent is totally different. The movie is a meditation on violence, on ennui, on a kind of hopelessness. It’s definitely cool, but the point isn’t that it’s cool. The point is that the VIP-level access to guns, women and booze and the complete lack of legal consequence with which Kitano’s character and his partners dole out murders are all the pinnacle of his existence and that they’re ultimately empty and meaningless.

Kitano’s character, Murakawa, is a long-in-the-tooth underboss in the Tokyo underworld, a man who goes about running his territory in a bored, workmanlike way, even as he’s threatening and later murdering the defiant proprietor of an unauthorized independent mahjong den. At one point, he and his underlings have the guy strung up from a crane over a bay, dunking him into the water for increasingly longer intervals. It’s clearly a more desirable outcome to just scare the guy and get him to start coughing up a cut to Kitano’s clan, but Murakawa seems to be genuinely curious how long the guy can hold out underwater. As he and his number two talk business, Murakawa almost forgets the guy is under and when he’s pulled up, he’s already drowned.

Oh, well. Murakawa just has them bury him. It’s a mild goof. Presumably they can just install somebody else to run that mahjong den.

The cheapness of death in Murakawa’s world does seem to worry him a little, though less than his relationship with his bosses: When his clan leader instructs him to take some troops to resolve a potential war between an allied clan and their rivals in Okinawa, he states his suspicions about the job right up front. But he goes anyway.

Kitano is known for shooting films quickly and without a lot of fuss. He’s no Kurosawa, whom actors have eulogized with funny stories about his tendency to spend sometimes hours accumulating takes just to ensure that one background character walks a convincingly samurai-like swagger. What you get with Kitano is a much more naturalistic framing and acting. It comes off as nonchalant, right up until somebody dies onscreen with absolutely no warning. Violence in Murakawa’s world is always shocking and unexpected to us, but it seems utterly run-of-the-mill to its inhabitants.

As Murakawa seeks out some young recruits to help fill out his roster on the way to the clearly dangerous mission, one takes offense at another enforcer’s insult and stabs him in the gut, right in front of everybody. The clan leaders and Murakawa himself are utterly unfazed. This is just the sort of thing that happens. Even the belligerents don’t seem to care all that much about the incident afterward: As the crew arrives in Okinawa, we see them seated next to one another in the passenger van full of yakuza toughs. The stabber offers his victim some ice cream, but he declines, saying with just the slightest look of petulance, “You stabbed me in the belly, and it still hurts.”

From the start, Murakawa’s mission is doomed. The audience feels it and so does he. A warning shot through the window of the flophouse where they’ll go to the mattresses shows him that his arrival has already been discovered. Almost immediately, he learns two things: That the allied clan he has come to help isn’t under the impression that the situation is anywhere near as dire as the fight for survival he was told to expect, and that he and his men are being targeted aggressively. Until about the halfway point of the movie, it looks like the entire story will escalate into a total bloodbath.

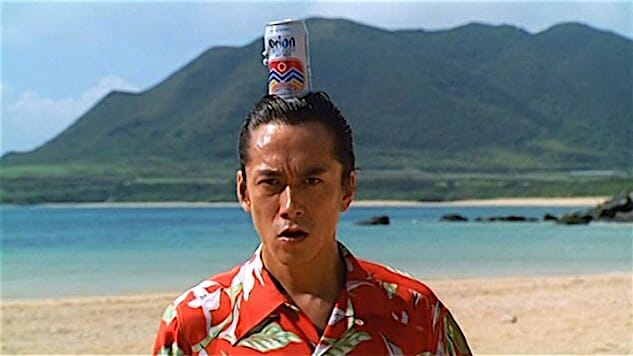

And then, faced with indecision from the top and in need of a place to cool their heels while the heat dies down, Murakawa and his remaining men hide out in a rustic cabin by the ocean, and the film takes on a completely different tone. An entire vast stretch of the middle of the film is Murakawa and his men messing around at the cabin—passing the time with games, using a passing thunderstorm for a shower to conserve water, and shooting Roman candles at each other during the night.

I’m glad I saw this movie after my boorish and dismissive teenage years, because I’d have hated it and completely missed the point. Murakawa’s attachment to a young woman, his casual opening up to her, the easygoing joys happening here, are all out of Murakawa’s grasp. He’s being given one last chance to experience them before they’re inexorably ripped away by the violence that suffuses his life. He can’t even escape it when he’s hiding from it: He gets his girlfriend by killing the man who is in the midst of attempting to rape her. One of his little games to unwind is to play Russian roulette with his colleagues (though it’s revealed he faked chambering the lethal round, essentially just scaring them). He seems unable to lay aside his gun even when unwinding, skeet shooting at a frisbee and even playfully popping a whole clip off at his men during that Roman candle play-fight.

Murakawa knows he’s doomed, of course. He foreshadows his own eventual end in his dreams, in which the gun he’s got to his temple isn’t empty. When it becomes clear his superiors aren’t answering him because he’s been sent to his death as a sacrificial pawn in his boss’s grander schemes, it seems clear there’s only one possible end to his story.

Sonatine remains a unique, tragic take on the gangster film genre because it’s about a man who has already had everything of any value taken from him, just as he’s figuring out what he can possibly do with that reality. It’s one of the only gangster films that manages to make violence seem as empty and pointless in its world as it is in ours. It’s fitting that it’s a movie you need to watch patiently.

Kenneth Lowe shoots fast because he gets scared first. You can follow him on Twitter or read more at his blog.