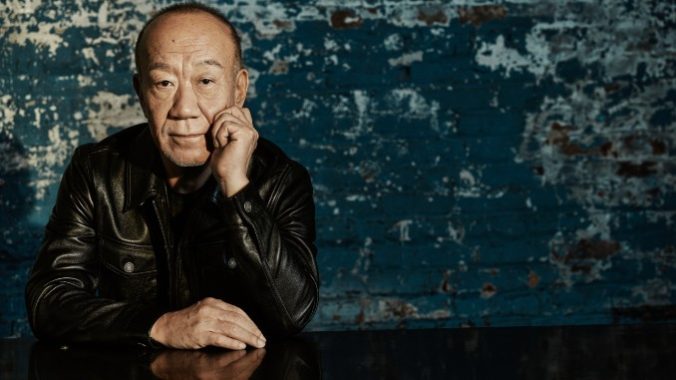

Joe Hisaishi has composed the soundtrack for every film Hayao Miyazaki has directed at Studio Ghibli, and his name is nearly as recognizable. Their collaboration began with the technically pre-Ghibli Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984) and has continued throughout the director’s many coming-out-of-retirement films. Given the ubiquity of Hisaishi’s melodies across TikTok and YouTube alongside art, cosplay and memes, it’s clear his music has had as much of an impact on the generation that grew up with Ghibli films as the directors’ fantastic visions and young heroines did. As we learned from Joe Hisaishi during our interview, even after nearly 40 years, Miyazaki is still able to surprise one of his closest collaborators—and impress him too.

While The Boy and the Heron is no doubt Miyazaki’s most personal film to date, it was also the infamously stringent director’s most hands-off production at Ghibli ever. That trust in his collaborators, to bring his new and likely final fantasy to life, extended to Hisaishi, who viewed the film for the first time in July of 2022 when the animation was nearly completed. “I leave it all up to you,” the director told him.

Composed and recorded in under a year (the film released in Japan on July 14, 2023 under the title How Do You Live?), the result is a minimalist score that reflects the psychological journey of its protagonist and, Hisaishi says, its writer-director. The soundtrack blossoms from the opening chords of Hisaishi’s piano as the first of several themes are introduced. The opening song, “Ask Me Why,” develops alongside protagonist Mahito as it is revisited across his coming-of-age journey, its melody a swelling up of “mono no aware” befitting the retrospective film. Gradually filling out as string and vibraphone accompaniment finds their voice, it follows The Boy and the Heron’s two halves: Mahito’s family’s retreat to a haunting mansion in rural, wartime Japan, and his fantastical journey across a world close to death.

Upon his traversal, Hisaishi’s instrumentation expands to incorporate a wide array of melodic percussion, rhythmic vocal chants and the gasps of a full orchestra. It’s a delight to hear Hisaishi following the crescendo of The Boy and the Heron’s narrative arc from these larger but still minimal compositions into contemporary symphonic catharsis, all in step with the wonders of Miyazaki’s fantasy—a fitting cadence for their collaboration. While the composer’s minimalist past has never found its way to the forefront of his work for Miyazaki, Hisaishi has continued to write original compositions and collaborate with composers like Terry Riley and Philip Glass throughout his career, standing alongside these household names as a peer.

At 72, Hisaishi shares Miyazaki’s desire to continue creating. During our interview, he mentioned that he hasn’t really had time to think about the direction of his music as of late. In the decade since working with Miyazaki on The Wind Rises, he’s created original compositions like the five-movement The East Land Symphony and new arrangements of Ghibli music for the studio, stage and hall, like the recently released A Symphonic Celebration and the near-total reinterpretations of his most iconic soundtracks in Songs of Hope: The Essential Joe Hisaishi Vol. 2. In 2014, Hisaishi also started his Music Future series, now going on its 10th season, which promotes lesser-known Japanese composers selected by Hisaishi.

Just as it would be reductive to consider Hisaishi’s compositions only in relation to Miyazaki’s films, though, the composer makes it clear that, to him, The Boy and the Heron is still Miyazaki’s achievement. He was impressed with what Miyazaki accomplished when he first previewed the animation five years into its production. “At that age,” he felt “to be able to make such a powerful thing, was quite amazing. And my sense of respect for him was renewed because of the strength of this film.”

Despite the minimal direction and the outsized influence of artists of all sorts on The Boy and the Heron, Hisaishi maintains that this is still Miyazaki’s film—his fantasy and his philosophy.

We sat down with Hisaishi to discuss The Boy and the Heron, his musical future, and his composing philosophy:

Paste Magazine: How did you feel when you learned that Hayao Miyazaki was coming out of retirement to create The Boy and the Heron?

Joe Hisaishi: I had thought that he would make another film, so I really felt like, “Oh yes he’s done it just as I thought he would.”

What were your initial impressions of the story? How did you first see it?

I saw this film for the first time on July 7, 2022. Usually, I’m shown storyboards and other materials, and we have discussions about the movie which I would then compose music for. But this time Hayao Miyazaki didn’t want me to have any kind of advance knowledge or preconceptions, so he didn’t show me anything. So, I saw it when it was pretty much finished, so it really was quite a surprise and an amazing sight for me to be able to see this at that stage.

Did you receive any more detailed direction from Miyazaki before you began your work on the soundtrack?

At that time when I saw the almost finished film, he said, “Well, I leave it all up to you.” Normally we would have meetings during the process—and it’s very important to have meetings between the director and the composer to find out where and what kind of music should we put in, etc.—but I only got some storyboards after I had seen that nearly completed film in July of last year. So, when he said “it was all up to me,” that was a real shock, because then it wasn’t as if we were going to have lots of direction as to what to do with the music.

With that shock—Is he really intending me to do everything without any meetings?—I sort of left things alone. I had some concerts I had committed to abroad. I thought maybe he would get back to me with what he wanted, but he didn’t say anything. So, I met with some of the staff who were in charge of the music and talked about when and where in the film some of the music should go. I created the demo tape. Even then there were hardly any changes requested.

So, the process of composing and getting the music done for this film was actually very smooth.

How did you arrive at the instrumentation and tones for the different themes iterated on throughout The Boy and the Heron?

When I saw the film, I realized that the first half, the first hour or so, was a rather real depiction of wartime Japan and the young boy. And then the second half was perhaps a more psychological, internal world of either the boy or maybe even Miyazaki’s own psychosocial, internal feelings. So, for the first hour I decided it would be good to have myself playing the piano without much extra instrumentation. And then the second half, because it was a fantasy world, I thought an orchestra would be fitting for that. But since it is still showing the personal feelings and internal psychological conditions of the hero and Miyazaki himself, I wanted to make it a rather minimal kind of music throughout.

This isn’t the first time that you’ve composed a score for Miyazaki’s last film. Is there a pressure that comes with “final statements” like The Wind Rises and The Boy and the Heron?

Well he’s been saying he’s not going to make any more films since Princess Mononoke, so I wasn’t really surprised and I didn’t feel that pressure that this might be the last film. But 10 years have passed since the previous film was made, The Wind Rises, so I was curious as to what kind of world he would create. And I was quite amazed that he really powered up his fantasy imagination. I felt that at that age, to be able to make such a powerful thing, was quite amazing. And my sense of respect for him was renewed because of the strength of this film.

What experiences and artists have influenced you the most in the past decade? Did any feel particularly relevant when you were working on this film?

For the last 10 years, of course I’ve done some composing for entertainment and films, but I’ve also composed quite a bit of contemporary classical music. I have a contract with Deutsche Grammophon so I record for them. And a couple of times the albums that I have recorded have hit the Billboard charts even. So, it’s been kind of busy. And worldwide I’ve had the opportunity to work with many of the major orchestras, so doing all these things is very stimulating on an everyday schedule for me. I’ve also done some conducting of classical music as well. So, I don’t have any time to compose really for myself, I’ve just been too busy and active in this way to have a chance to kind of reflect on what might be the direction or music. I’ve just been busy working.

Do you feel there is still more for you to create musically? What are you trying to achieve next with your composing and performing?

Because with this film, The Boy and the Heron, I was able to use the minimal music that I composed, I hope and wish that I will come across [another] film that I can also use the minimal music approach in scoring.

I think we’ll all be introspective after watching it. What’s your own philosophy? How do you live?

I really haven’t thought of it that way at all. My focus was on how to create the world that Miyazaki is showing. So, I took it as his personal history, and I didn’t really overlay my own thoughts or my own personal history to his personal history. Anytime that I work on a film, I’m an insider [laughs]. Working on the inside. So, I really can’t look at it as an audience member and try to critique it or try to figure what the film is all about.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

Autumn Wright is a freelance games critic and anime journalist. Find their latest writing at @TheAutumnWright.