Metrograph NYC’s Takeshi “Beat” Kitano retrospective began last week, runs until the 25th, and covers all the essential bases in his filmography. If you’re a veteran fan of Kitano’s work, take the series as a chance to revisit the best productions of his career, but if his name means nothing to you, then consider now the perfect opportunity to educate yourself on his cinema. Wherever you fall on that spectrum, there’s significance in Metrograph’s decision to pick Kikujiro as one of the retrospective’s two cappers: The 1999 film is both the culmination of Kitano’s early years as a director, and the best introduction to his movies for newcomers.

The truth is that no matter where you start in Kitano’s oeuvre, you’re going to end up watching a lot of greatness—but your image of Kitano, as is true of just about every director in the history of the medium, will hinge on how you make your initial acquaintance. Kitano first made his name as a filmmaker by shooting pictures cobbled together from the most aggressive elements of his persona, beginning with 1989’s Violent Cop and continuing with 1990’s Boiling Point, films that see him act at opposite ends of the law but which barely distinguish cops from robbers. Azuma, the thuggish protagonist of Violent Cop, isn’t yakuza, but that doesn’t mean you’d be pleased to meet him, while Uehara, the lunatic mobster of Boiling Point, is as vengeful as he is unhinged.

If, like me, you came to know of Kitano by these movies and by the other violence-inclined films of his early filmography, then you probably think of Kitano primarily as that: Disgruntled with a coarse approach to problem-solving and little patience either for human nonsense or the spoken language. In reality, there’s a softer side of Kitano peppered throughout his formative years as a director, in 1991’s Scene at the Sea, a subtly beautiful and calmly paced movie about a deaf garbage collector who learns how to surf, and 1996’s Kids Return, the story of two unmoored high school dropouts searching for any semblance of direction in their lives. (Caught in between these two films is Getting Any?, in which Kitano works in a mode aside from “gangster,” but which should not at all be characterized as “soft.” Getting Any? is a movie where, well, this happens:

Is Beat Takeshi the rough, taciturn, dispassionate killer of films like Boiling Point, Fireworks (known better by its Japanese appellation, Hana-bi), Brother and the Outrage duo? Is he the madcap responsible for the comic insanity of Getting Any?, or the artist behind evocative movies like Dolls and Scene at the Sea? Is he the daring rogue who usurped Shintaro Katsu’s throne in Zat?ichi: The Blind Swordsman?

He’s all of these things, but with the exception of a few stray details and niches, Kikujiro is the crossroads where the various personalities and fascinations of Kitano collide: His tough guy image, his obsession with prickly cops and steely yakuza, his surprising fondness for outcast or marginalized people, his impish sense of humor, his knack for maintaining serenity in between spats of brutal violence.

Kikujiro is the earliest confluence in Kitano’s filmography where his love of gangsters, his artistic aspirations and his humanism all pool together. These elements are each woven into the film’s fabric, but Kitano puts his yakuza layer first in order to unravel it over the course of the film’s running time. He plays the title character, Kikujiro, who doesn’t actually give his name until the end of the film—he’s a man cut from the same yakuza cloth as Uehara and Murakawa, the gruff, worn-down enforcer jaded by his lifestyle in Sonatine, which is to say that he’s the sort who treats every problem he runs into as the hammer treats a nail. But neither Murakawa nor Uehara is married to the also unnamed Mrs. Kikujiro (Kayoko Kishimoto), who has exactly zero tolerance for her husband’s belligerent stunting.

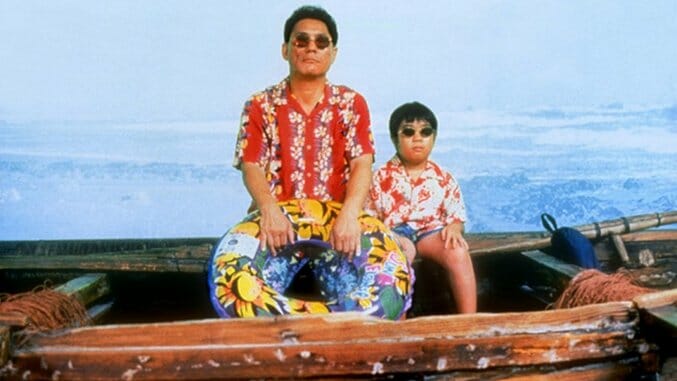

Apparently, that makes all the difference in the world: Kikujiro, rather than behave as a traditionally Kitano-ish movie and resolve all conflicts through beatings, sets the grouchy Kikujiro hither and thither across Japan with Masao (Yusuke Sekiguchi), a young boy searching for his lost mother. If it sounds sweet, well, it is, but if it’s sugary it’s at least never treacly. The movie is low on plot, it doesn’t engage with the aforementioned traits that helped Kitano build his reputation among international audiences and at first glance it’s kind of a lark. But there’s a good deal more to Kikujiro’s carefree frolicking: There’s self-exploration at play here, and lots of it, as Kitano uses Kikujiro the character and Kikujiro the movie to shed his raw, hardboiled skin minute by minute.

It begins with a simple but effective admonishment. “Quit playing gangster!” snaps Mrs. Kikujiro when he tries to extort some punk kids picking on Masao. Masao is so helpless and tiny, and his attackers are so obnoxiously teenaged, that you kind of want Kikujiro to smack them around, but his wife isn’t having any of it. (The teens look like they’re way more intimidated by her than they are by him, anyways.) That’s where it starts, the deconstruction of Kitano’s “don’t mess with me” exterior: A simple meta-acknowledgement that there’s more to him than bad-tempered cops and “shoot first, ask questions never” mobsters. Anyone who’d kept up with Kitano from the start knew this already—he first emerged in Japan’s comedy scene with Two Beat, the duo he formed with his friend Nir? Kaneko, and of course Getting Any? came out in 1995, four years before Kikujiro’s release—but Kikujiro works whether you’re well-versed in his career or not.

Kikujiro’s slow transformation takes place in intervals, often in response to his bad habits (like gambling on track cycling). Kikujiro isn’t a kid-friendly person (frankly, neither is Kitano), but beneath his bluster he’s human, and his humanity is evinced equally in expected and unexpected ways. We’re not surprised that he responds to a creepy pedophile, caught molesting Masao, by roughing him up and attempting to humiliate him: This falls well within his wheelhouse of behaviors, though the fury of his intervention does take us off guard. Until that point, Kikujiro regards Masao as an inconvenience instead of a responsibility. The run-in with the pedophile doesn’t rank terribly high on the nobility scale—wouldn’t anyone step in to help a kid in Masao’s situation?—but it’s the film’s gateway protective act, the moment where Kikujiro begins to act like a decent person.

From there the film is a warm-hearted fairy tale fare, a companion piece to recent films like Wes Anderson’s Moonrise Kingdom and Taika Waititi’s Hunt for the Wilderpeople. It is important to draw a distinction between the other gentle, sentimental movies Kitano made in the ’90s and Kikujiro. Scene at the Sea revealed his previously unseen range as a storyteller long before Kikujiro came to life, but he only directed that movie, whereas he is Kikujiro’s author and star all at once. By putting himself at the film’s center stage, he is able to address both his proclivities as a director and his persona as an actor with greater candor. The film feels like an act of self-examination as a result. If nothing else, it’s a necessary step in clarifying his cinema.

Take, for example, Kitano’s 1993 film Sonatine, which is subtly adorned with charm and humor in addition to prototypical Kitano elements of gunplay and yakuza violence. That film, alongside Getting Any? and Scene at the Sea, suggests enough nuance in Kitano’s style to keep him from being pigeonholed as a purveyor of gangster movies. But Kikujiro drove that truth home, pivoting him further away from yakuza films and toward a more diverse array of pursuits. After Kikujiro came Brother, which would turn out to be his last yakuza story for the next decade. Kitano followed that one up with Dolls, a stylized, tri-narrative arthouse joint, went on to piss off Katsu partisans by dyeing his hair blonde in Zat?ichi in 2003, and spent the next few years making Fellini-esque movies about the artistic process: Takeshis’, Glory to the Filmmaker! and Achilles and the Tortoise.

None of these three movies figure into the Metrograph retrospective, but Kikujiro’s presence makes their absence irrelevant—his longstanding bout of introspection started well before he began writing his autobiography on the screen with that surrealist trilogy. Maybe that threesome exists only because of Kikujiro. Without it we might actually just think of him as “the yakuza guy.” With it we think of him as a versatile director possessed of a dexterous voice, a precise sense of comic timing, a talent for orchestrating operatic violence and, above all else, startling compassion.

Boston-based critic Andy Crump has been writing about film online since 2009, and has been contributing to Paste Magazine since 2013. He writes additional words for Movie Mezzanine, The Playlist and Birth. Movies. Death., and is a member of the Online Film Critics Society and the Boston Online Film Critics Association. You can follow him on Twitter and find his collected writing at his personal blog. He is composed of roughly 65% craft beer.