The Best Last Festival Ever: Paste at the 2020 True/False Film Fest

Two Paste writers meet in Columbia, Missouri to write about all the documentaries they watched at True/False, the last great festival ever.

Images via True/False Film Fest

In the last hour of the last screening of his film that weekend, on the last night of the last festival ever, Khalik Allah came back into the theater, sat near the front, moved toward the back, moved toward the other side of the back, got up and left the theater and then, with 10 minutes to go, re-entered and said, loudly, “This is a motherfucking long movie.”

It’s true, IWOW: I Walk on Water is a very motherfucking long movie, some 200 minutes of wandering, absolute narcissism, an autobiographical screed written in 16mm, tape, Super 8 and HD. Ostensibly about the corner of 125th and Lexington in Harlem as much as it is about the director’s tumultuous, long-distance relationship with an ex-girlfriend as much as it is about his abiding devotion to using mushrooms to the detriment of any kind of humility, IWOW is so completely obsessed with itself as a cultural object that one wonders, 60 minutes in, why it even exists for anyone but its creator. About 70 minutes in, one wonders if he’ll record himself getting his dick sucked, and then 90 minutes later he records himself getting his dick sucked.

It’s gross to listen to, but it’s also a strikingly intimate exchange to witness, especially within the context of the film’s previous two hours of personal tribulation. Elsewhere, Allah introduces us to Frenchie, a Haitian immigrant who’s lived on the street for decades, diagnosed schizophrenic, struggling with addiction. Allah photographs him constantly, having previously made Urban Rashomon (2013) and Antonyms of Beauty (2013) about him, spends countless hours with him talking and shooting, Frenchie sometimes painfully lucid about life and sometimes totally gone, occasionally given to moments of intense anger or instability, even when Allah’s just trying to get him $20 from the ATM. Allah eventually takes him home, gets him a haircut and a shower and some new clothes, calls Frenchie his best friend while he records him, endlessly, transforming him into a movie’s subject. We watch white audiences watch Allah’s previous film, Black Mother, in museums. We hear Fab Five Freddy, one of many legendary artists with whom Allah crosses paths, warn Allah about letting his guard down around Frenchie. Our empathy feels twisted, in thrall to the film’s contradictions, wondering along with Allah if he is who he says he is.

It’s frequently beautiful, practically endowed with a knack for stumbling upon, too often, the sublime. While Allah rambles over top, saying what he deeply means as much as what he knows he deeply doesn’t, IWOW counters with a visual language that prioritizes the delicate connections between all the people he’s captured on film. Mostly, he does this through keeping his conversations non-diegetic, very rarely allowing the image to sync up with the sound, but also never really divorcing the sound from its context either. Long, unbroken shots of his ex-girlfriend’s face seem to touch on and occasionally embrace the rhythm of a conversation from another time, drawing those experiences into a single, felt moment. We understand more about the person inside the frame—or, at least, we begin to understand them the way Khalik Allah does. We get why he calls Frenchie his best friend, even if we’d like him to explain what he means by that. We’re bewitched by his many compulsions, by the way he feverishly, stubbornly documents everything, leaves seemingly nothing out. We maybe even start to fall in love with his ex, too.

The True/False Film Fest draws that kind of intimacy from all involved. The documentary films one sees in attendance typically fall into one of two lanes: informative and compelling stories about the extraordinary or the undertold, and unsparingly esoteric, autobiographical pieces, in which the filmmakers’ subjects are so personal the audience ceaselessly wonders where the truth begins and the fabrications—the narratives—end. This isn’t anything new to the festival, especially not to documentaries. One expects truth to be regularly interrogated the more control we get over our own stories and the ways in which we can tell them.

Catarina Vasconcelos’s The Metamorphosis of Birds (which had just premiered at Berlinale) tells of three generations in her family, casting actors in softly stylized vignettes that begin with the director’s grandfather, then follow her and her father, past her mother’s death, to an unknown horizon. Steeped in symbolism that barely escapes pretentiousness—letters of romantic wishing; peacock feathers lined up and counted; household trinkets and the empty corners they once filled now replaced by decades of houseplant growth left unabated—but all the more precious for it, the film reveals the life of her grandfather, a naval officer gone for months and months at a time while his six children transformed at a distance, his wife left to raise them and navigate their change. Fathers are far away, but desperate to send their love, and mothers die, in many cases their deaths essential, somehow, to their little birds leaving the nest, to them forging new symbols out there, on their own. Vasconcelos becomes a character in her own film as she mourns the loss of her mother, but she’s interested, too, in tracing her grief through her father’s grief, losing both his wife and his mother, losing the house his mother kept for him and his many siblings, losing time to the vastness of the ocean that kept his father so far away. In the midst of such closeness to the artist, we too feel the overwhelming space between these loved ones, space that was never closed, space we’re encouraged to confront in our own lives.

Sky Hopinka walks through such spaces, and films the ocean much the same way as Vasconcelos does, in his first feature, malni – towards the ocean, towards the shore. The translation of the title lies within it, representing a liminal reality known well to both those who live in the Pacific Northwest now and those now who know of the death myth of the Chinookan people, those who lived in the Pacific Northwest first. In joining two Native locals, Jordan Mercier and Sweetwater Sahme, as they go about their rituals, daily and communal and otherwise, Hopinka grafts a sense of spiritual wonderment onto the warmly mundane stories they tell. Cultivating a lush soundscape, and seduced by long walks through the Columbia River Gorge or in and out of outcroppings rising by seemingly abandoned beaches on the Pacific—forward and backward through the membranes that separate sacred terrains—the film uses the death myth as a way to convey the power of the region, of especially the Portland area. Half an hour outside of the city either way wait things almost magical to behold; those of us who live here can feel ourselves change the more we cross urban lines.

Urban lines limn the soul of A Machine to Live in, the feature debut of installation artists Yoni Goldstein and Meredith Zielke, a cosmic ode to Brazilian federal capital Brasília and the many spiritualities that have girded it. Like Werner Herzog’s The Wild Blue Yonder, Goldstein and Zielke’s hybridized doc takes on science fiction tropes to place the viewer within the perspective of an outsider, an alien, drawn to a civilization founded on symbols and geometry endowed with divine reasoning and purpose. Designed (functionally) by Oscar Niemeyer—who appears in the film explaining his architecture, parsing authoritarianism and communism while his face contorts into a deepfake of Jair Bolsonaro—Brasília represents a wide open hub of white edifices and sharp monuments to society as a functioning, living machine of moving parts, each person doing their duty, inscribing their time and care into the city as much as the city inscribes its ideal into each person. (We’re told that Brasílian citizens suffer inordinately from cataracts, their eyes’ only defense from the sunlight literally magnified dangerously by the bright-blank walls of the buildings towering around them.) Though the film too often threatens to obfuscate the same simple ideas in ever increasing abstraction, it rarely fails to mix so much dread with so much awe, casting a long, dark shadow over the futurism that has, so far, guided us to the edge of Dystopia. The sacred and the profane are written into the seams of the quotidian; Brasília grows much too quickly as bearded bikers ride by, their hogs in V-formation, flipping housing tenements the bird, lamenting the end of what the city used to be—a city that was ahead of its time, a city that dreamed of being a Utopia, a city that still does—by threatening to fist-fight Millennials.

One doesn’t have to look very far at a documentary film festival to find evidence of our failed human experiment, but stakes especially seemed higher as news and cases of COVID-19 spread while True/False finished up over the course of the first March weekend. In retrospect, not even two weeks later, True/False may turn out to be the last great film festival we’ll have for quite some time. It’s not hard to think in absolutes. What will a film festival even be anymore? As the weekend progressed, the signs became redder, culminating in the canceling of SXSW while T/F festivalgoers drank their water weight in beer. Hannibal Buress, his stand-up film without a premiere and stranded by the loss of the massive Austin festival, shipped Miami Nights—directed with as much flare as a stand-up film can offer by Kristian Mercado—to True/False to premiere in Missouri instead. Buress uses the special to dispel rumors that he is a greedy landlord. If you can overlook that he doesn’t succeed, you’ll probably enjoy it. He’s a wonderful storyteller even if he’s also a rich guy fully benefiting from the housing crisis.

Still, the responsibility of seeing persisted. We kept bearing witness, not for our own sakes, but to preserve whatever we could. This was going to be the last film festival ever, after all.

One of the festival’s best mechanisms for both preservation and discovery was the Neither/Nor repertory series, this year digging up rarely seen works from Missouri-born artists. Three films by video art pioneer Lisa Steele—shorts A Very Personal Story (1974) and Talking Tongues (1982), followed by 1980’s The Gloria Tapes—offered a cursory examination of her unique aesthetic, the former single-shot monologues (Steele recalling, as if for the first time, finding her mother dead; Steele playing the part of Beatrice Small, a woman abused by her husband) and the latter, the real gem, a character study shot as a series of sitcom-quality vignettes.

Steele plays Gloria, a woman with special needs who, upon becoming pregnant, must learn how to be a mother despite how easily flummoxed she is by every facet of adulthood. Steele’s fixed camera, roughed up and scarred by tracking lines, often meets Gloria mid-ramble as she talks to her social worker, her father, her sister, her boyfriend, the judge assigned to her case when she accidentally hurts her child. She defines her world through incessantly talking, trauma and bureaucracy mitigated by the retro primacy of the technology she’s using, all of it seeming cheap and made-for-TV-movie-like until Gloria, amidst her word diarrhea, drops an incisive clue as to the darkness that lies just outside of Steele’s hermetic frames. Once Gloria’s real story comes to light in The Gloria Tapes’ final moments, the rest of the film sharpens, painfully.

On the morning of the last day of the festival, the annual Weird Wake-up promised a special Wakaliwood-related treat, and with IGG Nabwana’s recent appearance at the Toronto International Film Festival to premiere Crazy World, his latest action opus, contending with a hangover seemed a small price to pay for free breakfast burritos and what we were told was a screening to keep in our “hearts forever.”

So commenced our fortunate viewing of Crazy World, preceded by a special True/False introduction and proceeded by a mostly successful Skype call with IGG Nabwana and a few familiar faces. The film is exactly what one might expect from the braintrust behind Who Killed Captain Alex? and Bad Black, an unbridled burst of creativity and communal art-making doused in blockbuster bloodshed and the eloquence of VJ Emmie, a guy who talks throughout the film, making jokes and explaining plot and pointing out allusions to previous Wakaliwood films. Sometimes he just yells, “Movie!” We cheer, because we know exactly what he means. Though Nabwana had apparently attempted to submit his films to the True/False festival twice before, undaunted by the fact that his films aren’t documentaries, the glee with which the audience received his film felt fitting considering that it kicked off the last day of the last festival ever. —Dom Sinacola

![]()

The films of Mike Henderson, part of the Neither/Nor repertory series, were perhaps my most exciting personal discoveries at True/False 2020. Nine of Henderson’s films played on 16mm prints, revealing his work to be both resourceful and inventive in their fashioning of props and abstract images from everyday household items. Full of ambiguity and perspective, no film I saw all week was more confounding than the 23-minute The Rocking Chair Film, which follows a man dragging a red rocking chair up and down a hill by rope. The man and the chair somehow converge with a film crew shooting a samurai movie, and two distinct realities twist together. Perhaps they collapse into one. Sharper and more immediate in its effect is Dufus (aka Art), a film in which Henderson repeatedly emerges from a closet dressed up as various Black stock characters of the ’60s and ’70s. He writes the identity he’s portraying on a canvas, with each character comically crossing out the one that came before as if to assert the veracity of his own outlook.

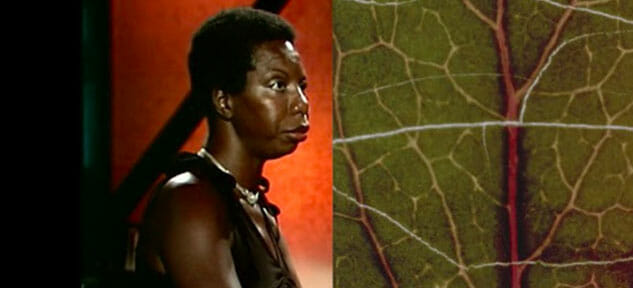

Henderson was born in Marshall, Missouri, and in addition to making films he played the blues. This background is never more expressly felt than in the excellent Down Hear, the film in the program most emblematic of what Henderson has described as his “blues cinema.” A kitchen-based recreation of African American history starting with the slave trade, Down Hear employs the simplest of set-ups. Made up in white face, Henderson is seen holding a switch and a rope, the other end of which is tied around a shirtless, blindfolded actor (his brother), who sits in a nondescript chair meant to be some sort of boat in the middle of an otherwise empty oceanic room. At the behest of the slave trader, the blindfolded actor paddles to a land unknown. The performances are exaggerated in their simplicity, mimetic and deliberate in ways that add yet another layer of distance and artifice to the proceedings. In this environment, the film is as much about the brothers making the film as anything else.

The two remain silent throughout, as if conjured ghosts, and Henderson speaks a bluesy narration over the pickings of an acoustic guitar, which together lend a sense of predestined propulsion to the events—a feeling that we are moving through a known history towards the present day. Eventually, the blindfold is removed, the slave begins to read, and as the 12-minute film progresses you can’t help but mentally trace this history up to the very making of the film, where these two men are creating magic in a kitchen with moving image technology. It is at once a realization of progress and failure, but its lasting impression lies in its soulful ability to imbue the characters’ direct movements—gestures made in a dissonant historical environment—with the muddy force of the past, all while channeling the present.

Where Henderson’s films feel inventive in their practical ingenuity, Ja’Tovia Gary’s The Giverny Document (Single Channel) feels so in structure, freely moving about three central threads, its unifying concern the autonomy of the Black female body. This is most clearly stated in the scenes that feature Gary interviewing Black women on the street, asking if they feel safe in their own bodies—a narrative direction partly inspired by, as Gary has mentioned, Jean Rouch and Edgar Morin’s Chronicle of a Summer (1961). Turns out, most do not, a fact all the more wrenching when a little girl with her father declares a safety that can only feel so absolute in a healthy childhood. These more digestible interviews are intercut with repurposed footage from previous Gary short Giverny I: Négresse Impériale that show her walking through the Giverny gardens made famous by the paintings of Claude Monet, and with a 1976 Nina Simone performance of the song “Feelings.” The three very different sources—verite, gallery and archival—in constant juxtaposition manage to coalesce, or rather play off each other, to create an incredibly sturdy whole. Off-the-cuff personal testimonies, in which genuine emotion is guarded but not invisible, is suddenly reinforced by Gary’s raw garden performance, which moves from serene walking among the garden’s lush landscape, jarringly cut, to her own cathartic screaming and Simone’s heartfelt concert. Thoughts that are either protected in speech or cannot be easily articulated in a street interview are suddenly given ample space to unravel in other planes.

Discussions about women’s safety were also prevalent in the Based on A True Story (BOATS) conference, put on by the Missouri School of Journalism in conjunction with True/False, which kicked off with a Wednesday night screening of Kitty Green’s The Assistant. Green’s film is sparse in style, a choice which helps it convey the cringe-inducing power dynamics of Hollywood through the simplest of images, each interaction and task charged with the palpable weight of what goes unsaid. The Assistant was additionally part of a larger conversation about composite characters, as Green crafted the titular employee from research and conversations with those who had endured similar experiences in the industry.

Composite characters are crucial to the films of Lisa Steele, another filmmaker highlighted in this year’s Neither/Nor series (see above), and also, in a different way, to John Skoog’s Ridge, a film consisting of stories compiled from and featuring residents of Skoog’s hometown in rural Sweden, creating an almost mythical, preternatural portrait of the region. For Skoog, it was less about crafting a character through assembled stories than using those stories to convey the ethos of a place. Ridge is a mostly shapeless viewing experience, in no pejorative sense, by virtue of how these understated stories are broken up by shots placing landscape, animals and machinery at the forefront. The town is defined not only by the movements of its people, but also by its industry and nature.

Like Ridge, Catskin is similarly concerned with depicting a land in flux, here following a right-wing family in Bavaria, Germany. Pinned outside their house is a Confederate flag, and inside resides a teenage boy who stores Hitler trivia at his fingertips. They occupy a cone of hatred that many could erroneously perceive as benign in its mundanity, not directly hurting anyone aside from themselves in their apparent isolation. Director Ina Luchsperger struggles to locate novel contradictions out of the generational portrait composed of the boy, his father and his disapproving, cat-loving grandmother. But the film is not without its compelling and layered observational moments, such as the grandmother comforting her severely injured cat, not to mention her collection of, as the title suggests, catskins shaved from former pets—images that question whether her good intentions have translated into effective care, or perhaps put that care beyond her control. What is missing more than anything is perhaps what is deeply felt in Ridge: a sense of place that breaks through mere staging grounds. All the makings of a haunted family portrait steeped in quietude are there, but Catskin never fully delivers on the uncanniness.

So Late So Soon, on the other hand, is a much different sort of family portrait. Intimate in its access and emotions, Daniel Hymanson’s film follows Chicago artists Jackie and Don Seiden in their aging years as they are forced to consider dour propositions, such as leaving their long-time Victorian home, several rooms of which Jackie has dedicated to her projects. The couple enjoy healthy bickering about typical marital qualms like who’s cleaning up around the house more, conversations complicated by Don’s decreasing mobility. They are not without long-term, lodged resentments, which come out in a frank conversation over Jackie’s choice to marry him and not pursue alternative paths. Don, the more grounded of the two, remains steadfast in his devotion and remarks on the multi-pronged meaning of what it is to build a life with a partner. The two alternate in sharing a perspective that can only come with age, and in between these musings, health issues plague each and limit potential creations. Jackie, for example, channels her vivacious spirit, still alive as ever but covered with the thin veil of accumulated years, from the house’s prop-filled rooms into computer slideshow stories, which she shows to an amused Don on camera.

So Late So Soon has the feeling of a successful “small film,” whatever connotations that may bring, but it is also more than that. It moves with modest and assured observation, its scope in content never wider than Jackie or Don’s interiority; even archival inclusion of Jackie’s educational art videos feels like a winnowing of focus rather than an expansion in the way it packs the present with meaning without contextualizing it. In this way, the film has power as a microcosm, the Seidens dedicated to confronting the inevitable losing battle against mortality with an (often frustrated) artistic spirit, even as that spirit wanes and shapeshifts in its final forms.

Such a love is not in the immediate cards for the subjects of Elke Margarete Lehrenkrauss’s Lovemobil, a film about two immigrant sex workers in Germany who rent overpriced roadside trailers from a modern Madame—a former sex worker herself named Uschi—to provide prostitution services to, most commonly, workers at a nearby plant. Uschi comes around asking for rent and ordering cleaning instructions, accompanied by frequent off-handed racist remarks. But she is also a vital source of trust and direction for the women. In a film full of warring internal impulses, Uschi is at once a provider and exploiter.

The camera is often hunkered down in a trailer, garish Christmas lights illuminating the front window for curious and longing passersby, while the women reflect on topics as varied as money, friends back home and the precarity of their situation. These feelings regarding the latter intensify when a fellow Lovemobil worker is murdered, and the two women internally debate their options. For Milena, that involves a trip visit to an old friend in Berlin who is unaware of her current occupation; for Rita, originally from Nigeria, the contemplation of fleeing. Shot in frequently stunning portraits that dignify the workers’ choices, the film also captures the needy and demeaning compulsions of desperate, violent men who stop by. The intimacy Lehrenkrauss achieves is remarkable, and as the women idly pass time in their trailers, full lives emerge, not defined by, though still bracketed by, their occupations. It is clear they merely want to afford a decent life, and for myriad reasons this incandescent camper along the nighttime road is the best vehicle available to achieve that goal, regardless of whether the road leads to hope or despair.

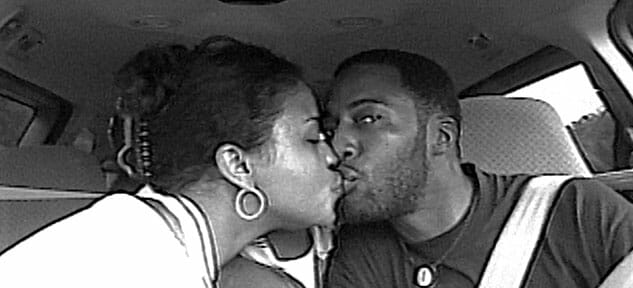

Hope and despair, in a very different vein, constitute the vacillating emotions of Garrett Bradley’s Time, a lyrical look at Sibil “Fox” Rich’s efforts to free her husband from a Louisiana prison, where he is serving 60 years for a botched bank robbery, as his sons grow up without a father in the home (Fox herself served a few years for aiding in the crime). Her dogged attempts to break through to an uncaring bureaucracy are crushing in and of themselves, but the mannered composure with which she takes denial after denial builds a remarkable portrait of strength and resolution.

One could ask how much Time grapples with the legitimate wrongdoing of the Rich parents, but Bradley does not give much credence to the question, because to do so would legitimize the system that, in doling out sentences so severe, ignores the humanity of the perpetrators in the first place. Sibil’s understanding of the morality of her and her husband’s situation is obvious, but also somewhat outside of the purview of Time, which is, for the better, much more concerned with the personal dynamic of the central relationship: how one sustains love and life when divided by an uncompromising and punishing system. The answer, in the case of the Riches, is Sibil’s home-made video diaries from a miniDV camera over the years, patched together with a score that gives the entire film the feel of a swelling epic—the intensely personal elevated to mythical proportions. Perhaps no film I saw at True/False had a more resonant climax, as Time truly builds to an ultimate moment of catharsis, which through its black and white imagery and heightened score fill an already deeply human moment with the additional powers of cinematic grace.

Directly preceding Time was Kevin Jermove Everson and Claudrena Harold’s short film, Hampton, which features the University of Virginia gospel choir singing for the camera. Everson has now made several films about UVA and its history, but of the ones I’ve seen this is the most directly experiential, the choir often singing to the camera, the music imbuing the images with an easy rhythm somewhat uncommon in Everson’s often stark, though still excellent, work.

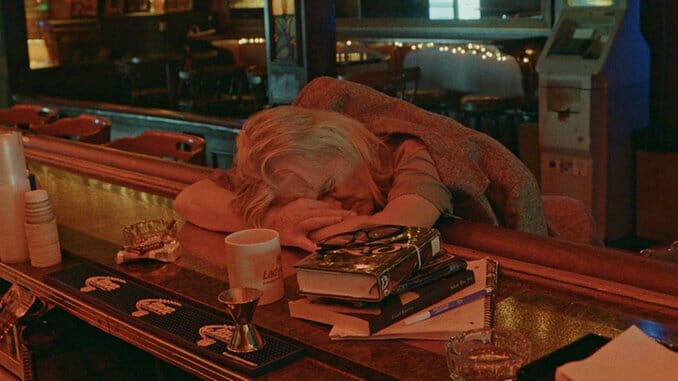

Songs of the soul also flow from the drunken mouths of the jukebox-loving inebriates in Bill and Turner Ross’s Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets. The Ross brothers have created a prototype barroom experience, crafting something like their own 10 ideal pub characteristics in the mode of George Orwell’s “The Moon Underwater,” to glean moments that speak to the nature, and for some the necessity, of communal drinking. It is closing night for the fictionalized Roaring 20’s in Las Vegas, a real bar operating in their home base of New Orleans, and the regulars, led by local professional actor Michael Martin and otherwise populated with true bar-frequenting nonactors, have come together to kiss their favorite watering hole goodbye. Its much-discussed fictional framework is merely that—a framework—beneath which legitimate human interactions play out, with characters representing themselves and actually drinking the night away. There is authentic war vet commiseration and romantic longing, bartender-led singalongs and, inevitably, one guy trying to fight another “with eyes tattooed on his eyelids.” The holy trinity of dive bar life—despondency, frivolity and pugnacity—is present and spiritually enriching.

As always, the Ross bros depict those before their camera with the deepest care and respect. Pangs of regret and anguish sound between moments of hilarious drunken crosstalk, with Martin’s character pulling in close his younger, rambunctious four-eyed friend and imploring him not to likewise spend his life in a bar. The film runs the gamut of drunken night emotions, from wistful dancing to maudlin bouts of self-loathing, but the mood is never pinned to any specific emotion; it is less about one peak or one valley than it is about creating the shape of a waveform in itself. Yet each crest and trough is tinged with the fleeting feeling of the other: To be low is to be touched by the immense depth of drunken feelings, and to be high is to ride forth in embarrassing obliviousness. Such is the case when a 60-year old “regular” gleefully lifts up her shirt at fellow patrons and the camera to declare she still has “30-year-old titties”; an observing young man, in fits of laughter, is inclined to agree. But somehow the images never whiff exploitation; they radiate a sense of humanity and an understanding of these American outcasts, who will surely flit from one closing bar to the next. What awaits them thereafter is a mystery, and perhaps a sad story we do not need to know. What this all means for them personally, on a larger scale, is for another film. This one is concerned with the motion of life in its alternative community, a custom-made island for misfit toys. —Daniel Christian

Daniel Christian is a writer and filmmaker based in Columbia, Missouri. In addition to Paste, he has written for Filmmaker Magazine and No Film School. You can follow him on Twitter.

Dom Sinacola is Associate Movies Editor at Paste and a Portland-based writer. You can follow him on Twitter.