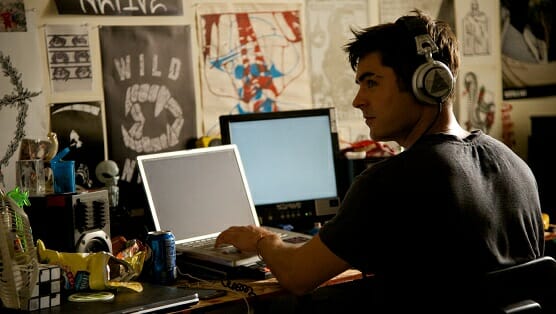

I knew I was in trouble fairly early on in We Are Your Friends, when aspiring DJ Cole (Zac Efron) plays one of his tracks for his hugely successful mentor James (Wes Bentley). In the scene, we’re clearly supposed to think Cole’s track is mediocre—the problem is it doesn’t sound all that different from James’ stuff, or any of the other music that blares constantly throughout the film. My fears about where all this was headed were confirmed about 80 minutes later, in a scene where Cole plays his latest and greatest composition to a music festival packed with fans. Sure enough, the music sounds just as repetitive and unoriginal as the track at the beginning of the movie that we were encouraged to laugh at, only now the takeaway is evidently supposed to be that Cole is some kind of artist. The whole thing plays like an EDM version of the Sylvester Stallone-Dolly Parton country-and-western vehicle Rhinestone, where Sly sings as badly at the end as he did at the beginning, but for some reason everyone treats him like he’s turned into Merle Haggard.

Lest you fear I’m giving anything away, the finale of We Are Your Friends—like virtually everything else in the movie—is preordained from the moment the viewer steps into the theater. Ostensibly a film about coming of age and making tough choices, what We Are Your Friends is really about is setting up ridiculously inconsequential obstacles and then knocking them down—Cole’s path to adulthood and success is about as smooth as something can be and still be called drama, and about as dull as something can be and still be considered a movie. The basic story follows Cole and his friends as they dream of getting out of the San Fernando Valley to find success on the other side of the hill in Los Angeles proper; the key question in their lives is when to give up and go work for a friend in real estate (Jon Bernthal, whose performance is easily the most lively thing in the movie) who can give them a stable living. Cole’s dream is to become a huge DJ, and I won’t waste your time with the other friends’ dreams because the movie barely bothers to either—in spite of the title, this is Cole’s story, and it’s probably just as well given that the filmmakers struggle to make even that work.

Director Max Joseph’s background is largely in commercials and web videos, and it shows—he doesn’t develop a single character or idea beyond the most obvious initial impression. I acknowledge that going after somebody for directing music videos and commercials is unfair and lazy criticism, since some of the greatest we’ve ever had—David Fincher, Ridley Scott, Alan Parker, et al.—have advertising backgrounds or experience. The problem with We Are Your Friends isn’t that its director comes out of commercials, but that the movie is a commercial that spends 100 minutes trying to sell ideas, attitudes and performances it doesn’t seem to believe in. In his defense, Joseph works hard, utilizing every bit of stylistic pizzazz he can to make every shot as visually pleasing as possible. He has to, because the movie has nothing else to offer.

Emily Ratajkowski’s performance serves as a useful starting point for examining what’s wrong with the picture, since another guy who came out of commercials—the aforementioned David Fincher—got great work out of her in Gone Girl. The difference between the way Fincher “sells” Ratajkowski as a performer and the way Joseph does it is instructive. In Gone Girl she’s a fully realized character though she’s only in a few scenes; in We Are Your Friends she’s on screen for half of the movie (she’s the “love interest”) and does little more than stare vacantly into space or, in the slightly more important moments, into Zac Efron’s eyes. I know that Ratajkowski is a model, but she comes across as slightly less comfortable on camera here than The Fat Boys did in Disorderlies—maybe she knows how bad the movie she’s in is.

Ratajkowski certainly can’t be blamed for the fact that her character has nothing to do; this movie shows so little interest in women that it makes Entourage look like a Chantal Akerman film. Ratajkowski is the only female character given a semblance of a personality, and even in her case the personality isn’t really demonstrated on screen—we’re supposed to accept it on faith because the male characters seem to treat her more seriously, and the fact she went to Stanford is mentioned in passing. The other women are decoration at best and objects of sexual derision at worst—the guys in the movie (none of whom are great prizes, believe me) treat them like baggage handlers treat luggage. And unlike Entourage, the movie doesn’t even have the courage of its juvenile convictions—there’s a scene where Efron’s character punches a guy out for talking about Ratajkowski in the same demeaning way every other woman has been treated unironically throughout the rest of the movie. Why are we suddenly supposed to be appalled by this? Oh yeah, because the guy doing the talking is some kind of establishment yuppie, a point made by the abundance of expensive cheese that surrounds him.

The movie’s refusal to commit to its own lame-brained worldview is a major problem that extends far beyond the treatment of women. For much of its running time the only pleasure the film offers is the milieu of sex, drugs and music that it allows the audience to vicariously experience, but then it takes a truly weird turn by killing off one of Efron’s friends when he overdoses at a party. Thus begins a long stretch of moralizing right out of the old Hollywood Production Code—first we’re encouraged to enjoy a superficial lifestyle, then the movie punishes anyone in the audience who was stupid enough to buy what it was peddling. I have no clue what Joseph is getting at here; if you want to make a party movie, make a party movie, but what’s the point of suddenly shifting gears and telling the audience how empty it all is, especially when the film is a hell of a lot more convincing showing the fun of sex and drugs than it is at depicting the repercussions.

Indeed, if We Are Your Friends wasn’t so forceful in ramming false moral choices down the viewer’s throat, it might work as a kind of guilty pleasure, an empty but entertaining time-killer. But it’s just so damn heavy—the whole movie feels like an anchor attached to the audience’s ankles. The key question in the film is whether or not Efron’s character will follow his dream or go the safe, stable route, but it’s a bogus dilemma; Joseph and co-screenwriter Meaghan Oppenheimer stack the deck so heavily in favor of the former that there’s no choice at all. The “real” job they give Cole is one in real estate where he is forced to rip people off and kick them out of their homes; on the other hand, they give him so few obstacles in his path to the top of the DJ-ing world that he would have to be positively insane not to choose it. The result is 100 minutes of waiting for a character to make a choice that was already determined the second he stepped on screen.

Watching We Are Your Friends, I couldn’t help but be reminded of the 1988 Tom Cruise vehicle Cocktail, another dumb—but far more entertaining—combination of escapism and moralizing starring a charismatic young actor. Cocktail was a hit, and maybe We Are Your Friends will be too; if it is, I hope Efron follows it up in a way similar to Cruise, who quickly left this kind of shit behind to do Rain Man and Born on the Fourth of July back to back. Efron has just as much power on screen as Cruise, and I think he’s got the acting chops as well—he’s genuinely terrific in Neighbors and At Any Price, and he elevates middling fare like 17 Again with his razor-sharp sense of comic timing. I can’t imagine what director wouldn’t want to use him given his combination of talent, looks and bankability, which makes his presence in movies like We Are Your Friends a bit of a mystery—isn’t he getting better offers than this? Are the people he works with—agents, managers, etc.—encouraging him to take the money and run? Zac, I don’t know who told you this movie would be a good idea, but you might want to stop listening to them—they are not your friends.

Director: Max Joseph

Writers: Max Joseph and Meaghan Oppenheimer

Starring: Zac Efron, Emily Ratajkowski, Jonny Weston, Wes Bentley, Jon Bernthal

Release Date: August 28, 2015

Jim Hemphill is the writer and director of the award-winning film The Trouble with the Truth, starring Lea Thompson and John Shea. He has written about movies for Filmmaker Magazine, Film Comment and many other publications. You can follow him on Twitter.