Time Capsule: AC/DC, Highway to Hell

Every Saturday, Paste will be revisiting albums that came out before the magazine was founded in July 2002 and assessing its current cultural relevance. This week, we’re looking at AC/DC’s measure of raunchy apostasy that few rock rebels have ever achieved so meteorically, as the five-piece was knocking on the door of tragedy.

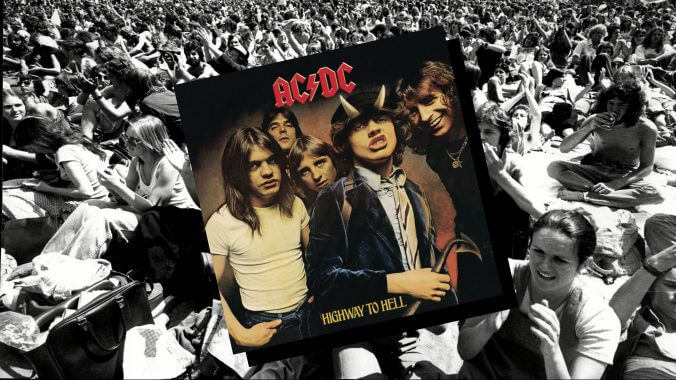

Photo by David Thorpe/ANL/Shutterstock

“I’ve got big balls, they’re such big balls and they’re dirty balls. And he’s got big balls and she’s got big balls, but we’ve got the biggest balls of them all!” Those lines filtered through the speakers of my Magnavox CD player in my childhood bedroom when I was six years old. I was not yet truly aware of what they meant; I had balls but I didn’t know who else had balls, but AC/DC seemed to know and wanted to let everyone in on the secret. I poured over my copy of Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap (the American release, which heartbreakingly omitted the original, 1976 Australian version’s closing track, “Jailbreak”), scratched the disc up from being seven or eight and having no tangible understanding of what it meant to take care of your possessions. Even when the CD began to skip, I still blared “Big Balls” at full-blast until my parents yelled at me to turn it down and rarely listened. No parental displeasure could interrupt me from fulfilling my destiny of getting forever stoked on a song about testicles and its spectrum of possession.

I’d sit at my grandparents’ dining table and draw the Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap album cover—designed by Hipgnosis (who also came up with the cover of a few underground records like Dark Side of the Moon, Houses of the Holy and Wings at the Speed of Sound)—over and over again from memory, and I’d even make up my own self-portraits and throw a black box over my eyes, too. My dad used to drive a Dodge pickup truck that still had a tape-deck in it, and we’d listen to a cassette of Stiff Upper Lip nearly every time we shared a ride together. I was young and fascinated by the effort it took to rewind the tape every time, just so we could go back and hear the title track bleed into a song called “Meltdown” again. I think, if I had to guess, that was when I fell in love with AC/DC for real, ditching my attraction to the Beatles and Elvis for stone-cold rock ‘n’ roll. The band would become my personality until I was knocking on the doorstep of teenagerdom, and it was a passionate, generational love affair.

But, really, all of this immersion started with an album cover. It was five Australian men looking disaffected in five different ways. In the very back was bassist Cliff Williams, who couldn’t quite seem to figure out what was going on. There’s Malcolm Young, giving a subtle pursed lip-look that puts blue steel to shame. Peeking his head up next to Malcolm is drummer Phil Rudd and, on the very far right of the portrait is Bon Scott cracking a million-dollar smile and sporting an all black outfit bedecked with gold chains. But front-and-center is Angus Young, the proverbial shredder of the Baby Boomer Generation, with his hair perfectly quaffed and a set of devil horns sticking clean out of his news cap. He’s holding a devil’s tail while coiling his lip into a snarl and donning the schoolboy outfit he’s worn (in blue, red, green and black iterations, respectively) for 50 years. There’s nothing larger-than-life about this album cover, but the songs behind it would change the world of rock music forever.

I used to have a poster of the Highway to Hell cover image on my bedroom wall and, feeling inspired by it, I’d steal my mom’s blank CD-ROM jewel cases and draw my own album covers for the front jacket. I’d walk around the house toting my new “studio album” packed with a tracklist of fake songs and all, even playing a tune called “The Backdoor” for my dad on my baby acoustic guitar and making up the words and melody on the spot. I was something of a rock star; the lead singer and guitarist of a band called Power Chord of the Shock Rock (abbreviated to the acronym PC/SR to match the name-styling of my heroes, with a lightning bolt in place of the slash). One morning, I’d even recruited a few friends at school to be in PC/SR, and we rehearsed on the playground after lunch—banging sticks against rocks and plotting out our World Tour—only for them to quit before the 3 PM dismissal bell. In my head, I’d already made a dozen platinum albums, because I could shred on my cherry-red Fender squire (despite only knowing the riff to “Smoke on the Water,” which my dad taught me how to play incorrectly).

But 26 years earlier, in New York in January 1979, executives at Atlantic Records held a meeting about how to remedy AC/DC’s continued failure to detonate properly in the United States. The band’s last record, Powerage, only peaked at #133 on the Billboard 200 and it didn’t minister a hit song of any kind—at least nothing that any rock stations were picking up on their rotations. Atlantic put out a live record, If You Want Blood You’ve Got It, with the hopes of it offering the same success to AC/DC that an album like Alive! did for Kiss in 1975, but its sales numbers were even worse than Powerage’s. Why couldn’t AC/DC mirror their Australian and European popularity in North America? Was it Bon Scott’s rasping braggadocio, or something much less tangible? From a business perspective, a blame had to be thrown onto somebody—and it ended up being George Young, Angus and Malcom’s older brother, who’d produced the band’s first five albums, was a founding member of The Easybeats and co-wrote international hits like “Love Is in the Air” and “Friday on My Mind.”

The idea was to have Eddie Kramer captain AC/DC’s sixth studio album (if you, like me, consider High Voltage and T.N.T. separately), and the Cape Town-born producer was something of a legend in the music industry already—having engineered albums by Jimi Hendrix, Led Zeppelin and Peter Frampton, and having produced Carly Simon’s debut and Kiss’ four most-successful releases of the 1970s. But, the sessions Kramer held with AC/DC were massive failures. Bon Scott’s alcoholism had gotten worse, and there was a doomed energy in the air—likely a result of George Young’s ousting and Kramer’s sudden imposed presence in the studio. After Malcolm threatened violence if Kramer wasn’t fired, AC/DC’s manager Michael Browning canned the audio auteur for the up-and-coming, 31-year-old producer Robert John “Mutt” Lange and, together, he and the band stepped out and made Highway to Hell.

Highway to Hell is a measure of raunchy apostasy that few rock rebels have ever achieved so meteorically. Gret Knot said it best when reviewing the album for Rolling Stone in 2003: “The boys graduate from the back of the bar to the front of the arena.” That much is true; you can viscerally hear the five-piece turning into rock folklore in real-time across 10 loud, hip-thrusting, death-defying tracks. This wasn’t an ascension like that of Guns N’ Roses on Appetite for Destruction. No, the success wasn’t applicable from the jump. AC/DC had worked long hours to become the biggest rock band in the world. A year prior, Powerage was their most eclectic offering at the time—as the project brandished songs like “Down Payment Blues,” “Riff Raff” and “Up to My Neck in You,” fuse-blowers that didn’t kick up a fuss culturally (like those on Highway to Hell and Back in Black would over the next three years) but rattled the walls enough to bolster AC/DC into the hands of Lange and vault them into the echelons of rock immortality for good.

There will never be a world where “Highway to Hell” isn’t the most famous song on the album. You don’t have to like AC/DC to be able to recognize Angus Young’s opening riff, either. It’s synonymous with not just the 1970s, but with rock ‘n’ roll altogether. Atlantic Records advised against the band naming the record Highway to Hell (they also detested Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap and, as a result, the album didn’t receive a United States release until 1981), but AC/DC were providing their own personal commentary for a life spent on the road—which had become topical, given how their explosion in America in 1977, on the back of no radio support, led to a live reputation and fandom that, in 2024, still rages on faithfully.

“A lot of it was bus and car touring, with no real break,” Angus told Guitar World. “You crawl off the bus at four o’clock in the morning, and some journalist is doing a story and he says, ‘What would you call an AC/DC tour?’ Well, it was a highway to Hell. It really was. When you’re sleeping with the singer’s socks two inches from your nose, that’s pretty close to Hell.” “Highway to Hell” came about when Angus and Malcolm were broke and holed up in a rehearsal studio in Miami. Angus played the opening riff and then, in a flash, Malcolm jumped on the drum kit and they demoed it together. The story goes that an engineer’s child messed around with the demo tape and unraveled it, but Bon Scott MacGyver’d it back to life and preserved the sketch of what would become one of rock music’s most ubiquitous tracks.

From the moment Bon begins singing “Living easy, loving free, season ticket on a one-way ride,” there’s a certain tenacity to the recording. If you’ve ever watched one of AC/DC’s live performances taped before Bon’s passing, you’re probably already well-familiar with the outline of his penis and how he sang each and every track as if it was about to burst through the seams of his too-tight denim pants. For all of the ways that Angus’ guitar-playing arrives with a pulverizing, hard-nosed energy, “Highway to Hell” is nothing without Bon’s bravado—a coat of demonic varnish pressurized from singing through clenched teeth about to shatter. And then, miraculously, Angus’ solo turns Bon’s unkempt vocal ugliness into a thing of chaotic beauty. There’s a ferocity here—a stoic, unbothered declaration of disregard for the five albums that came before Highway to Hell. AC/DC had finally made a commercial darling, effectively erasing the middling sales numbers of everything from High Voltage to Powerage. In a pan-flash so seismic its embers still flicker, “Highway to Hell” is one of rock ‘n’ roll’s greatest exorcisms and introductions.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-