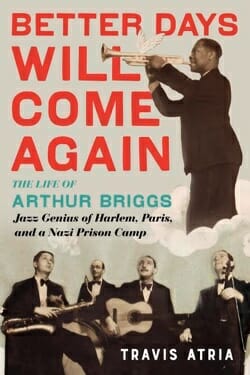

The Incredible Story of Arthur Briggs, the Harlem Jazz Trumpeter in a Nazi Prison Camp

Arthur Briggs’s life was Homeric in scope. Born on the tiny island of Grenada, he set sail for Harlem during the renaissance, then to Europe in the aftermath of World War I, where he was among the first pioneers to introduce jazz music to the world. During the legendary Jazz Age in Paris, Briggs’s trumpet provided the soundtrack while Hemingway, Fitzgerald, and the rest of the Lost Generation created their indelible masterpieces. By the 1930s, Briggs was considered the “Louis Armstrong of France,” and was the peer of the greatest names of his time, from Django Reinhardt to Josephine Baker. When the Nazis stormed Paris at the start of World War II, they arrested Briggs and threw him in the prison camp at St. Denis, where he spent four years on starvation rations, and where he directed the brass section of an orchestra comprised of fellow prisoners. Below is an excerpt from Paste contributor Travis Atria’s illuminating new biography of Briggs, Better Days Will Come Again.

In October 1940, pioneering jazz trumpeter Arthur Briggs, a man known as the “Louis Armstrong of France,” was captured and sent to the Nazi prison camp at St. Denis. There, he helped form and lead a classical orchestra. Music was a fixture of life in St. Denis, as it was in most Nazi camps. The Nazis allowed their prisoners to form orchestras, or Lagerkapellen, for many reasons. Music was used to accompany manual labor and to humiliate prisoners, who were nearly starved and worked to death, and were still forced to summon the strength to sing. In death camps it was used to “drown out the screams of the dying.” Here, Arthur Briggs was lucky. St. Denis was a prison camp, not a labor or concentration camp, meaning the orchestra didn’t have to force men to work or mask the sounds of death. Instead, Briggs performed at the pleasure of his captors.

He soon became the center of the camp’s musical life, forming a small jazz combo and singing Negro spirituals in a vocal trio with two other black prisoners. In addition, the commander at St. Denis made Briggs camp trumpeter. His duties were to blow the Reveille at seven in the morning for the wake-up call; at nine a.m. for first checkup, when the Nazis examined the rooms; at five or six in the evening, depending on the season, for second checkup; and at nine at night to signal lights out. The men stood for hours at these checkups, while the guards scoured their barracks, flipped their mattresses, and ransacked their few possessions for contraband.

He soon became the center of the camp’s musical life, forming a small jazz combo and singing Negro spirituals in a vocal trio with two other black prisoners. In addition, the commander at St. Denis made Briggs camp trumpeter. His duties were to blow the Reveille at seven in the morning for the wake-up call; at nine a.m. for first checkup, when the Nazis examined the rooms; at five or six in the evening, depending on the season, for second checkup; and at nine at night to signal lights out. The men stood for hours at these checkups, while the guards scoured their barracks, flipped their mattresses, and ransacked their few possessions for contraband.

Briggs’s trumpet duties earned him special comforts, including food privileges. The daily ration at St. Denis was a ‘Komisbrod’ (a roll of black bread) per man per week, cabbage soup for lunch, and a similar soup for dinner, or a spoonful of ersatz jam with a small lump of margarine. Often the soup had worms floating in it. Sometimes it had horse teeth. Briggs recalled, “When I got to the camp and saw what they were dishing out for food, I said, ‘I couldn’t blow my instrument on that.’” Briggs was granted permission to eat with the kitchen staff, which was a mixed blessing. The food wasn’t better; there was just more of it. Instead of living near starvation, Briggs had the luxury of desperate hunger.

The winter of 1940 hit like it had a score to settle. It was the first of three record-breaking winters, all of which Briggs spent in captivity. “Freezing,” wrote William Webb, a prisoner who kept a secret diary in the camp. “Tripe stuff for dinner—awful. No more fresh stuff left.” Two days later, the hot water was gone. Each morning broke like a brittle bone. The men awoke and trudged to the washroom, where they splashed frigid water on their blue-cold bodies. Within days the pipes froze, and there was no water at all.

Briggs played a concert on New Year’s Eve, but it was only a bit of levity on the gallows. His guts were twisted with hunger. In four days he had to join his rag-tag orchestra, mount a makeshift bandstand, and in the bitter cold, play the hardest show of his life. Otto von Stülpnagel, Nazi commander of occupied France, had demanded a concert.

Briggs was to perform in the St. Denis theatre, which the prisoners built themselves using Red Cross boxes for the stage and cigarette tins for stage settings. Several artists among the men designed decoration and scenery. “It looked like a real theater,” Briggs recalled, “with a big podium raised for concerts.” Here the internees put on shows for each other, including a rendition of Cinderella; here the commander of Nazi France waited to be entertained.