Jonathan Gould Discusses His New Talking Heads Book Burning Down the House

Over the course of eight studio records, two live albums and the greatest concert film ever made, Talking Heads established themselves as among the best and hippest groups of the late 1970s and early 1980s. Fronted by David Byrne, who was joined by drummer Chris Frantz, guitarist Jerry Harrison and bassist Tina Weymouth, the New York rock band was forged in the nascent punk club CBGBs—the same one that launched everyone from Patti Smith to Television to the Ramones—before achieving the sort of mainstream success few of their peers enjoyed. Decades after their creation, songs like “Psycho Killer” and “Once in a Lifetime” remain embedded in the culture, a living soundtrack of the existential questions that still haunt modern life. In 2023 when Talking Heads’ celebrated 1984 movie Stop Making Sense returned to theaters, it was hailed all over again—as was the innovative quartet at its center, even though they had broken up in the early 1990s, never reforming and only rarely speaking to one another.

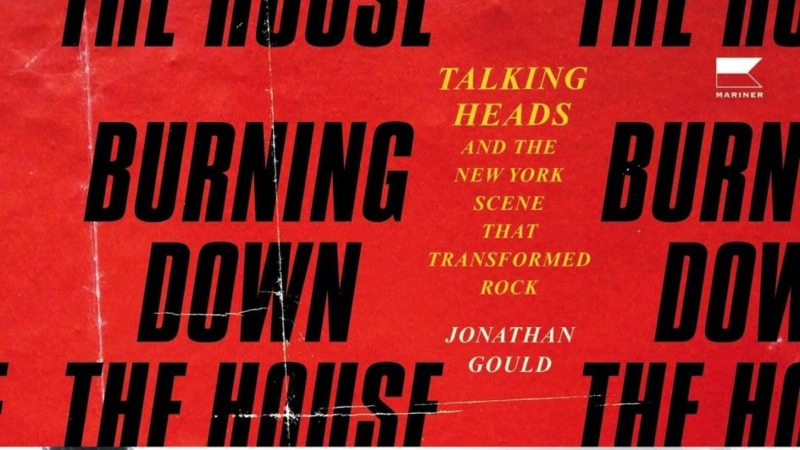

Fifty years after the band’s first public performance, Jonathan Gould has given serious thought to the group’s legacy, as well as the city that served as their backdrop. Coming out June 17, Burning Down the House: Talking Heads and the New York Scene That Transformed Rock is a hefty tome devoted to chronicling their career from its early days to its bittersweet aftermath. But Gould, a writer and musician who previously authored books on the Beatles (Can’t Buy Me Love: The Beatles, Britain, and America) and Otis Redding (Otis Redding: An Unfinished Life), places that history in a broader context, tracing the political and economic realities of New York at the time when Byrne and his bandmates first started gigging. Along the way, he also dissects the rock ‘n’ roll myth of bands as de facto families and the tendency of white musicians to crib from the Black progenitors of the art form. Burning Down the House documents the famous infighting that affected Talking Heads nearly from the start, but it’s less tell-all than sober sum-up, diving deep into the music to determine why it has endured.

Gould, a native New Yorker, is close to the same age as the band members and was making music around the same time as they were. “As the albums came out, what I was very impressed with was their artistic evolution,” he recalled over Zoom this week. “[It was] certainly one of the major attractions, that there was a real arc to their career that they started in one place and they ended up in another.”

Encompassing punk, new wave, pop, hip-hop, country and, eventually, African rhythms, Talking Heads helped set the stage for the musical adventurousness of the 1980s that would soon be embraced by the likes of Peter Gabriel and Paul Simon. Gould didn’t speak to the band members—each, according to the author, politely declined his interview requests—but he did get in touch with many in their circle, and he goes the extra mile investigating how, for example, Byrne’s autism both positively and negatively impacted Talking Heads. Below, he and I discuss the band’s continued relevance, his decision not to include one of Byrne’s most controversial public moments, and why he doesn’t think Talking Heads will ever do a reunion tour.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

It has been 37 years since Talking Heads released a studio album. Why do we still care? Why are they still so cool?

Two things come to mind. One is that they broke up. Another group that hasn’t gone away is the Beatles: After 10 years, they called it a day, and that has a way of freezing people in their prime at the height of their powers. If people rediscover [Talking Heads’] music, it’s there in its ideal form.

The other thing that comes to mind is in relation to the film Stop Making Sense, which was rereleased. Seeing it again in a big theater at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, what I noticed is there’s almost nothing anachronistic about it—nothing about the way the film looks, the film was made, the music. Talking Heads were committed to the idea of modernity from the very beginning. They didn’t pretend to be Western outlaws or any of the common postures that rock stars have gravitated toward in terms of the way they dress or behave. That’s one of the reasons they’re still around.

When you [work on a Talking Heads book] for four or five years, you become something of a lightning rod for everybody you meet, their feelings about Talking Heads. I’m very well aware of the number of people who are avid fans who discovered them through their parents—their parents were really into this band. Now, sometimes that’s the kiss of death. (laughs) But in their case, once the next generation got over the fundamental principle that you shouldn’t like what your parents like, there was a lot to like. The music still feels contemporary.

Of all Talking Heads’ achievements, I wonder if Stop Making Sense is most responsible for preserving their mystique.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-