The 35 Best Movies on Hoopla (October 2025)

Similar to the library-accessible streaming service Kanopy, Hoopla is a completely free (no ads) way to access movies, books, comics and audiobooks—all with just a library card. Where Kanopy boasts deals with more arthouse-oriented fare like The Criterion Channel, the best movies on Hoopla offer an exciting mix of indies, studio films and new releases.

I can’t emphasize this enough: It’s free. No ads, simple account set-up, decent user interface. When our streaming budgets are pushed to the limit by lackluster original content, turn to an easy, non-pestering service that’s available on desktop and mobile. We broke down the best movies on Hoopla, which range from stone-cold classics to artful indies. If your library isn’t serviced by Hoopla, there’s a good chance it falls under Kanopy’s jurisdiction. As a good Midwesterner, though, Hoopla’s where I fall, and I have plenty of pleasant first-hand experience. On Hoopla, there’s something for everyone, from modern hits to established giants of the canon.

Here are the 35 best movies streaming on Hoopla right now:

1. The Host

Year: 2006

Director: Bong Joon-ho

Stars: Song Kang-ho, Byun Hee-bong, Park Hae-il, Bae Doona, Go Ah-sung

Rating: NR

Before he was breaking out internationally with a tight action film like Snowpiercer, and eventually winning a handful of Oscars for Parasite, this South Korean monster movie was Bong Joon-ho’s big work and calling card. Astoundingly successful at the box office in his home country, it straddles several genre lines between sci-fi, family drama and horror, but there’s plenty of scary stuff with the monster menacing little kids in particular. Props to the designers on one of the more unique movie monsters of the last few decades–the mutated creature in this film looks sort of like a giant tadpole with teeth and legs, which is way more awesome in practice than it sounds. The real heart of the film is a superb performance by Song Kang-ho (also in Snowpiercer and Parasite) as a seemingly slow-witted father trying to hold his family together during the disaster. That’s a pretty common role to be playing in a horror film, but the performances and family dynamic in general truly are the key factor that help elevate The Host far above most of its ilk.—Jim Vorel

2. Blind Willow, Sleeping Woman

Year: 2023

Director: Pierre Földes

Stars: Kwon Hae-hyo, Lee Hye-young, Park Mi-so, Song Seon-mi

Rating: NR

There are already several wonderfully meditative, carefully realized adaptations of Haruki Murakami short stories – namely Korean director Lee Chang-dong’s Burning and Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s 2021 Oscar-winning Drive My Car – yet many of the Japanese literary icon’s most famous works have long been deemed unfit for cinematic translation. This likely has to do with Murakami’s penchant for employing elements of magical realism. The vivid, often fantastical scenes he creates through prose could easily come off as awkward, incongruous or simply unsatisfying on the screen, even within the seemingly limitless capabilities of modern VFX technology. By adapting several Murakami short stories with particularly surreal elements via animation in Blind Willow, Sleeping Woman, writer, director, animator and composer Pierre Földes is able to evocatively distill the mystical streak that permeates loosely connected plotlines, unfolding in the wake of the Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami that hit Tokyo in 2011. The film incorporates six of Murakami’s short stories from three separate collections: The Elephant Vanishes, After the Quake and Blind Willow, Sleeping Woman. Even casual Murakami readers will recognize that The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle, the (slightly altered) first chapter of which was originally published as The Elephant Vanishes, is a major component of this film. It’s not the sole focus, but it lushly conjures many specific details, from Komura’s missing kitty-turned-vanished wife to the inquisitive teenage neighbor who allows him to camp out in her backyard. Though the film only delves into the first chapter of the novel as it appears in Elephant, it’s difficult to imagine another film tackling The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle and succeeding in capturing the hazily idyllic yet overwhelming foreboding atmosphere that Blind Willow does so effectively. The triumph and allure of Blind Willow, Sleeping Woman is owed to the specific animation style that Földes utilizes, which is a visually intriguing combination of motion capture and 2D techniques. Blind Willow, Sleeping Woman is a refreshing take on a popular author’s oeuvre. It’s also ambitious in its own right, especially as it arrives on the heels of the aforementioned Murakami adaptations that have received substantial acclaim.—Natalia Keogan

3. A Love Song

Year: 2022

Director: Max Walker-Silverman

Stars: Dale Dickey, Wes Studi, Michelle Wilson, Benja K. Thomas, John Way, Marty Grace Dennis

Rating: PG

One of my grandpas died right before the pandemic. My grandma met someone in the middle of it. Her new relationship wasn’t well-liked in my family, but it made her giddy as a schoolgirl—finding another cowboy to look at livestock with, play cards with, to make dinner with. When I was little, she used to live in a trailer, driven out into the woods and bricked into the earth. I see a lot of her in writer/director Max Walker-Silverman’s sublime debut, A Love Song, where a widow and widower find a teenage verve for each other—weathered but not beaten in the sun of the American west. Faye (Dale Dickey) lingers at one of several campsites surrounding a crawfish-filled lake, waiting for Lito (Wes Studi). She’s not sure he’ll arrive, but as we observe her daily routine—listening to birds, making coffee and catchin’ crawdads as she spins the radio dial in search of another country tune—her uneasiness is couched in a kind of contentment. Walker-Silverman situates us the same way, with ogling environmental photography that takes pleasure in a rare flowery purple on dried brown dirt and Faye’s tininess in relation to the lake, the mountains and the overwhelming dark (or starry splendor) of night. The location is spectacular but, conspicuously, never as enthralling as the actors. When they eventually meet up, top-level turns from Studi and Dickey combine for a contained masterclass, a relationship that’s been nursing a low flame for decades. They’re shy, affectionate and oh-so awkward—spurred by nervous attraction and lingering guilt surrounding their lost loved ones—with an honesty that makes the most of a sparse and quiet script. A Love Song’s a brief and pretty little thing—less than 90 minutes—with the warm melancholy of revisiting a memory or, yes, an old jukebox love song. Walker-Silverman displays a keen eye, a deep heart and a sense of humor just silly enough to sour the saccharine. Dickey takes advantage of one of the best roles she’s ever had to tap into something essential about loss, lonesomeness and resilience. Her performance is a gift, one given by someone who knows about simple pleasures and those that last—how both are important, and how they might not always be separate.—Jacob Oller

4. The Truman Show

Year: 1998

Director: Peter Weir

Stars: Jim Carrey, Laura Linney, Ed Harris

Rating: PG

Peter Weir’s delightful, hilarious The Truman Show wouldn’t get made anymore. It’s a star-studded event film centered around a simple and dystopian premise: Jim Carrey’s eponymous character has unwittingly been raised from birth as a reality TV star and only now has begun to suspect that everybody in his life is a hired actor. Carrey’s clear-eyed acting is worlds away from the zany roles that catapulted him to fame a few short years prior, though, as was typically the case with Carrey roles in the ’90s, copious amounts of special effects work go toward creating a believable simulated reality for Carrey’s endearing everyman to be trapped within. The heartfelt monologues and devastating revelations as he fights to escape his gilded cage shine all the brighter for it. The fight to break away from control, from a sanitized and curated existence dictated by a literal white father figure in the sky, rings alarmingly two decades years later, when social media has made performative brand managers of us all. Truman is an unlikely and often hapless hero in his own story, but his eventual hijacking of his own narrative—and his final defiance of his literal and figurative creator figure—form one of the most heroic cinematic arcs of the last 20 years. —Kenneth Lowe

5. The Naked Gun: From the Files of Police Squad!

Year: 1988

Director: David Zucker

Stars: Leslie Nielsen, Priscilla Presley, Ricardo Montalbán, George Kennedy, O.J. Simpson

Rating: PG-13

The final hoorah from the comedy trio David Zucker, Jim Abrahams and Jerry Zucker—ZAZ for short—The Naked Gun is so stupid it’s hilarious. This, of course, was ZAZ’s secret weapon in films like Airplane!, and in Leslie Nielsen’s stone-faced imbecility they found their muse. A former dramatic actor, Nielsen rejuvenated his career by playing Frank Drebin, a hapless L.A. police detective trying to prevent the assassination of Queen Elizabeth. (And in his courting of possible femme fatale Priscilla Presley, he taught us the importance of wearing full-body condoms.) A wonder of slapstick and deadpan silliness, The Naked Gun makes jokes about terrorists, gay panic, boobs, even “The Star-Spangled Banner.” There’s a character named Pahpshmir. Good lord, it’s all so gloriously idiotic. —Tim Grierson

6. Fist of the Condor

Year: 2023

Director: Ernesto Díaz Espinoza

Stars: Marko Zaror, Gina Aguad, Eyal Meyer, Man Soo Yoon

Rating: R

A silent, hairless man made of muscle. A mysterious text, filled with ancient ancestral ass-kicking knowledge. An animal-based fighting style. A possible identical twin. A revenge-tinged showdown. These are the throwback components making up the neo-classical Chilean martial arts movie Fist of the Condor. Marko Zaror, who’s come stateside before as a villain squaring off against Keanu Reeves and Scott Adkins, reunites with filmmaker Ernesto Díaz Espinoza for a transcendently simple standalone feature. If you’re not familiar with Zaror (I was not), Fist of the Condor is the perfect introduction to the secret weapon best known by direct-to-video action enthusiasts and Robert Rodriguez completionists. He’s jacked, he’s stoic, he can pull off all sorts of silly stuff with a straight face and, most importantly, he’s a great fighter. If you’re looking for 85 minutes of old-school action and the best pure martial arts movie of the year, look no further. This naturally sets expectations high, possibly for a film with the same charming disdain for reality as Riki-Oh: The Story of Ricky. But Fist of the Condor, though not without its moments of wry humor and gory excess, is a much quieter experience. Think ‘70s kung fu, with its casual lore, minimal characters and mythic tone. Fist of the Condor isn’t non-stop brawls, but something that could inspire the next Wu-Tang Clan. Incorporating both Zaror’s intended introspections and the magical abilities martial arts movies love to unlock through those limit-pushing actions, the training montages do what they’re meant to do: They train us. We learn to love this disciplined dork, and anticipate him putting his education to use in actual fights. Espinoza (who wrote, directed and edited the film) builds this tension perfectly, then reminds us in the moment, quickly cutting between Zaror’s rapid pummeling of a wooden Wing Chun dummy and him putting those same flying fists to work on some poor biker’s face in a barroom confrontation. It’s amazing to watch the human body move so fast, and more amazing to watch it exactingly execute the same sequence of moves again and again. Zaror is a phenomenal talent, displaying the kind of precision and awareness that lets Espinoza shoot wide and long. There’s not much cheating here. Espinoza can experiment with camera placement without worrying about ruining a particular strike or dodge, simply because his stars are such beef machines. He makes it all simple, which gives the indie film room to breathe. Other action movies from 2023 may have bigger setpieces, crazier stunts, more scenes of Tom Cruise trying to kill himself. But none are as ambitious and successful in their pure dedication to good ol’ fashioned hand-to-hand fighting as Fist of the Condor.—Jacob Oller

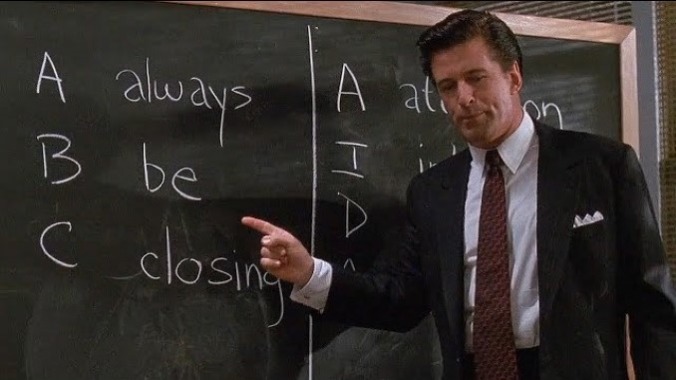

7. Glengarry Glen Ross

Year: 1992

Director: James Foley

Stars: Al Pacino, Ed Harris, Jack Lemmon, Kevin Spacey, Alec Baldwin, Jonathan Pryce, Alan Arkin

Rating: R

Surely somewhere on the Internet there’s a catalog of all the potboiler plays that have been turned into lifeless movies, wherein their minimal settings came off as flat rather than intimate or claustrophobic, and the surgically written prose came off as stilted rather than impassioned. Glengarry Glen Ross is the exception and the justification for all noble stage-to-screen attempts since. This adaptation of David Mamet’s Pulitzer Prize winning play about workingman’s inhumanity to workingman still crackles today, and its best lines (there are many) have become ingrained in the angrier sections of our collective zeitgeist. James Foley directs the playwright’s signature cadence better than the man himself, and the all-star cast give performances they’ve each only hoped to match since. Mamet, for his part, managed to elevate his already stellar material with his screenplay, adding the film’s most iconic scene, the oft-quoted Blake speech brilliantly delivered by Alec Baldwin. This is a film worthy of a cup of coffee—and, as we know, coffee is for closers only. —Bennett Webber

8. Punch-Drunk Love

Year: 2002

Director: Paul Thomas Anderson

Stars: Adam Sandler, Emily Watson, Philip Seymour Hoffman, Luis Guzman

Rating: R

It may be hard to recall now that we’ve all rallied around his talent—allowing him to transcend the stigma of his Netflix deal while he still profits ludicrously off it—but there was once a time when the world doubted Adam Sandler. Long before the Safdies or even Noah Baumbach got their time getting tight with the Sandman, we have P.T. Anderson to thank for inspiring such hope. Compared to the scope of There Will Be Blood, or the melancholy of Boogie Nights, or the inexorable fascination at the heart of The Master, or the obsession and obfuscation of Phantom Thread, Punch-Drunk Love—a breath of fresh, Technicolor air after the weight of Magnolia—comes off like something of a lark for Anderson, setting the stage for the kind of incisive comic chops the director would later epitomize, and complicate, with Inherent Vice. A simple love story between a squirmy milquetoast (Sandler) on the verge and the woman (Emily Watson) who yanks him back to life, Punch-Drunk Love is as confounding as it is a delight, an expression of unmitigated, sputtering passion—sad and febrile and, most importantly, optimistic about what anyone is truly capable of doing. This might be as sincere as Anderson gets. —Dom Sinacola

9. Tangerine

Year: 2015

Director: Sean Baker

Stars: Alla Tumanian, Mya Taylor, Karren Karagulian

Rating: R

One of filmmaker Sean Baker’s best, Tangerine‘s fable of Christmastime sex workers navigating love and loss in Hollywood is everything the indie great is known for: intimate, warm, silly, heartfelt and just scuzzy enough. Shot entirely on iPhones, this subversive holiday film celebrates found family in donut shops and laundromats and bar bathrooms. It reminds us that sometimes, the best gift of all is a friend who’ll lend you their wig while yours is in the wash. Kitana Kiki Rodriguez and Mya Taylor carry the film in all its emotional and tonal complexity, while Baker’s compassionate interest in folks just outside the margins make the filmmaking’s guerilla-esque stylings seem more loving than exploitative. Approaching his subjects with empathy, and giving them so much space to suck us into their world, is utterly within the holiday spirit–even if a car wash sexual encounter might not be as wholesome as something from Jimmy Stewart. But for a certain kind of person, and for Tangerine‘s very certain kind of friendship, “Merry Christmas Eve, bitch” is all that needs to be said. —Jacob Oller

10. Force Majeure

Year: 2014

Director: Ruben Östlund

Stars: Johnnes Kuhnke, Lisa Loven Kongsli, Clara Wettergren, Vincent Wettergren, Kristofer Hivju

Rating: R

Hidden behind this uncomfortably snickering fable about modern masculinity is something with no real patience for heteronormative nonsense. Though Force Majeure is mostly about a seemingly good dad who makes a bad split-decision while on vacation with his seemingly perfect family, the film would rather question the more primeval forces that bind us: monogamy, safety, companionship, blood and lust. This isn’t about a father who, in a brief moment of weakness, failed to protect his family, it’s about the dynamics of any relationship: Can we ever know the people we love most? Östlund asks this over and over, wreaking sickly funny havoc upon his male protagonist’s ego as he builds to a sweet little climax wherein this beaten-down bro revels in the chance to show his family his true colors. —Dom Sinacola

11. Leave No Trace

Year: 2018

Director: Debra Granik

Stars: Ben Foster, Thomasin McKenzie, Dale Dickey, Dana Millican, Jeff Kober, Alyssa Lynn

Rating: PG

It takes all of Leave No Trace before anyone tells Will (Ben Foster) he’s broken. The man knows, perhaps ineffably, that something’s fundamentally wrong inside of him, but it isn’t until the final moments of Debra Granik’s film that someone gives that wrongness finality, that someone finally allows Will to admit—and maybe accept—he can’t be fixed. Why: Granik affords us little background, save tattoos and a few helicopter-triggered flashbacks and a visit to the hospital to acquire PTSD meds all implying that Will is a military vet, though what conflict he suffered and for how long remains a mystery. As does the fate of Will’s deceased wife, mother to teenage girl Tom (Thomasin McKenzie). As does the length of time Will and his daughter have been living off the grid, hidden within the more than 5,000 acres of Portland’s Forest Park, a damp, verdant chunk of the city’s northwest side overlooking the Willamette River. As does the pain at the heart of Leave No Trace, though it hurts no less acutely for that. Toward the end of this quietly stunning film, Tom shows her father a beehive she’s only recently begun to tend, slowly pulling out a honeycomb tray and tipping a scrambling handful of the insects into her cupped palm without any fear of being stung. Will looks on, proud of his daughter’s connection to such a primal entity, knowing that he could never do the same. Will begins to understand, as Tom does, that she is not broken like him. Leave No Trace asserts, with exquisite humanity and a long bittersweet sigh, that the best the broken can do is disappear before they break anyone else. —Dom Sinacola

12. Driveways

Year: 2019

Director: Andrew Ahn

Stars: Hong Chau, Brian Dennehy, Lucas Jaye, Christine Ebersole

Rating: NR

Loneliness looks different for the lonely depending on their circumstances, and Andrew Ahn’s sophomore feature, Driveways, captures that spectrum through character. For single mom Kathy (Hong Chau), loneliness means sitting amongst the clutter of her dead sister’s house, dwarfed by junk crammed into every corner and piled to the ceiling. For widower Del (Brian Dennehy), loneliness is literal: He lives alone in the house he shared with his wife for decades before her death, their only daughter having relocated to Seattle years prior. For Kathy’s son Cody (Lucas Jaye), loneliness is a weird blessing: Social anxiety makes him hurl; he’s happier reading or playing videogames. Still, Cody wants to play with other kids, or at least he wants to want to, and Kathy, being a concerned mom, knows that even pleasant self-imposed isolation has adverse effects on children. Fortunately for both of them, Del is eager for company, though, as a man of a certain disposition, he’s not exactly the type to appear eager. Regardless, while Kathy cleans out her sister’s place, Del and Cody slowly bond, though their chummy and charming friendship has an expiration date: Kathy and Cody are out of towners staying in the unnamed New York hamlet where Del dwells only for as long as it takes to get the house settled and up for sale. As their time is short, so too is Driveways, a brisk, breezy 80 minutes where conflict is minimal and compassion prevails. Driveways is a simple picture about simple acts of human kindness; Ahn shot Driveways several years ago, and he premiered the film a hundred years ago at the Berlin International Film Festival in 2019, so neither he nor writers Hannah Bos nor Paul Thureen mean to make any comment on what gets airplay on the daily news, but American antipathy is a real thing and Driveways is the accidental salve the rest of us need for our current era of callous stupidity. –Andy Crump

13. Ida

Year: 2013

Director: Pawel Pawlikowski

Stars: Agata Trzebuchowska, Agata Kulesza

Rating: PG-13

A compelling examination of how the past can shape us even when we don’t know anything about it, Pawel Pawlikowski’s quiet Polish film takes place in the 1960s, when World War II has ended but still grips people’s lives. In the title role, Agata Trzebuchowska—with a well-tuned balance between naivete and curiosity despite being a non-professional actor—plays a nun-in-training who learns that her family was Jewish and killed during Nazi occupation. She embarks on an odyssey to find their graves with her cynical, alcoholic aunt Wanda (Agata Kulesza), former prosecutor for the communist government. The relationship between the two characters grows more and more complex as they go deeper down the rabbit hole of their family’s past. Shot in black-and-white and academy ratio (1.37:1) by cinematographers Łukasz Żal and Ryszard Lenczewski, Ida uses its frame to distinct effect, often resigning characters to the lower third of the screen. The effect can be unsettling, but intriguing; that space could contain the watchful power of Ida’s lord, but it could also be nothing more than an empty void. After a life of certitude, Ida has to decide for herself. —Jeremy Mathews

14. Riders of Justice

Release: May 14, 2021

Director: Anders Thomas Jensen

Stars: Mads Mikkelsen, Nikolaj Lie Kaas, Andrea Heick Gadeberg, Lars Brygmann, Nicolas Bro, Gustav Lindh, Roland Møller

Rating: NR

The Danes have a long, long history of dark fairy tales. Scrub away the Disneyfication and Hans Christian Andersen will keep you up at night. That tradition continues with Riders of Justice, a fable about the importance of men getting therapy, disguised as a revenge thriller. Mads Mikkelsen’s bushy beard and the film’s Christmas setting lend the movie to an irony-laden, moral-toting mythos–and its black humor, tough action and complex emotional core work just well enough that, like reading a classic fairy tale, you’ll be along for the ride after coming to terms with a few tonal surprises. Yes, writer/director Anders Thomas Jensen co-wrote the abysmal The Dark Tower adaptation. Try not to hold that against him: He’s also written dozens of Danish films and won a few Oscars. Riders of Justice sees him reunite once again with Mikkelsen, who has appeared in all the films Jensen has helmed. This time, the Danish demigod is playing military man Markus, a recent widower who finds out that the circumstances around his wife’s death might be more than accidental. A trio of deadpan doofuses a la The X-Files’ Lone Gunmen (all variations on crackpot tech or probability nerds) notice that hey, maybe this train crash that very specifically killed a gang member who was turning on his biker brethren might not have been coincidence. Led by Otto (Nikolaj Lie Kaas), the man who barely escaped death by giving up his seat to Markus’ wife, these hilarious and affecting goobers–basically who Dr. Ian Malcolm would actually be–push a theory that helps emphasize the film’s elegant prologue scene: That tangible, trackable cause-and-effect ripples are more trustworthy, satisfying and ultimately true than any sort of fate or randomness. Naturally, this leaves poor, bottled-up Markus with only one logical, self-destructive outlet: Murderous revenge. But Riders of Justice is no John Wick. Jensen films some impressive action–intimate and upsetting rather than basely satisfying–and peppers in absurd or absolutely arid humor as his team of fragile, needy, odd, obsessive men seek closure, but ironically this fable is far more grounded than anything as mythic as the American Action Hero. Though there’s a bit of a moral jumble to its ultimately productive deconstruction of the revenge movie and it’ll certainly never be a bedtime story, Riders of Justice still has a savvy lesson to impart to the grown-up children raised on the strong and silent type.–Jacob Oller

15. Man on Wire

Year: 2008

Directors: James Marsh

Rating: PG-13

In 1974, high-wire walker Philippe Petit fulfilled a longstanding dream by sneaking into New York’s World Trade Center, stringing a cable between the tops of the two towers, and (with almost unfathomable guts and without a net) walking across it, back and forth, for almost an hour. The man is clearly a nut, but he’s also a great storyteller with a heck of a story, and Man on Wire gives him a chance to tell it. Petit’s stunt was both an engineering challenge and a test of, well, a test of something that most of us don’t possess in this much quantity. Filmmaker James Marsh uses standard documentary techniques, combining new interviews, as well as a satisfying pile of footage and photographs, with re-enactments that both build the kind of suspense more suitable to a caper movie and shade the film’s climactic moment with all due respect for (yet, thankfully, no literal mention of) the visceral symbolism of the two buildings that are no longer there. The title comes from the report written by a police officer on the scene; he was more than a little uncertain about how to respond to the audacity on display. —R.D.

16. Hundreds of Beavers

Year: 2024

Director: Mike Cheslik

Stars: Ryland Brickson Cole Tews, Olivia Graves, Wes Tank

Rating: NR

Hundreds of Beavers is a lost continent of comedy, rediscovered after decades spent adrift. Rather than tweaking an exhausted trend, the feature debut of writer/director Mike Cheslik is an immaculately silly collision of timeless cinematic hilarity, unearthed and blended together into something entirely new. A multimedia extravaganza of frozen idiocy, Hundreds of Beavers is a slapstick tour de force—and its roster of ridiculous mascot-suited wildlife is only the tip of the iceberg. First things first: Yes, there are hundreds of beavers. Dozens of wolves. Various little rabbits, skunks, raccoons, frogs and fish. (And by “little,” I mean “six-foot stuntmen in cheap costumes.”) We have a grumpy shopkeeper, forever missing his spittoon. His impish daughter, a flirty furrier stuck behind his strict rage. And one impromptu trapper, Jean Kayak (co-writer/star Ryland Brickson Cole Tews), newly thawed and alone in the old-timey tundra. Sorry, Jean, but you’re more likely to get pelted than to get pelts. With its cartoonish violence and simple set-up comes an invigorating elegance that invites you deeper into its inspired absurdity. And Hundreds of Beavers has no lack of inspiration. The dialogue-free, black-and-white comedy is assembled from parts as disparate as The Legend of Zelda, Charlie Chaplin’s The Gold Rush, JibJabs, Terry Gilliam animation, Guy Maddin and Jackass. Acme is namechecked amid Méliès-like stop tricks and Muppety puppetry, while its aesthetic veers from painting broad violence upon a sparse snowy canvas to running through the shadowy bowels of an elaborate German Expressionist fortress. Guiding us through is Tews. He’s a wide-eyed mime with a caricatured lumberjack body, expertly gauging his expressions and sacrificing his flesh for the cause. His performance takes a little from the heavy-hitters of the form: The savvy romanticism of Harold Lloyd, the physical contortions of Buster Keaton, the underdog struggles of Charlie Chaplin, and the total bodily commitment of all three. You don’t get great physical comedy accidentally. Just as its intrepid idiot hero forges bravely on despite weathering frequent blows to the head, impaled extremities and woodland beatings, Hundreds of Beavers marches proudly towards the sublime transcendence of juvenilia. In its dedication to its own premise, Hundreds of Beavers reaches the kind of purity of purpose usually only found in middle-school stick-figure comics or ancient Flash animations—in stupid ideas taken seriously. One of the best comedies in the last few years, Hundreds of Beavers might actually contain more laughs than beavers. By recognizing and reclaiming the methods used during the early days of movies, Mike Cheslik’s outrageous escalation of the classic hunter-hunted dynamic becomes a miraculous DIY celebration of enduring, universal truths about how we make each other laugh.–Jacob Oller

17. The Gold Rush

Year: 1925

Director: Charlie Chaplan

Stars: Charlie Chaplin, Mack Swain, Tom Murray

Rating: NR

The Klondike gold rush made the perfect setting for Charles Chaplin’s tramp to run wild. Chaplin took all the motifs he could find from adventure novels, melodramas and other stories of the northern frontier, tossed them in a blender and served up a collection of what would become his most famous scenes. He finds humor in peril—with a suspenseful teetering cabin scene, as well as starvation (when he famously makes a meal of his boot) and of course finds time to show off with his dancing roll scene. However, no one has succeeded in finding any humor in the atrocious voiceover Chaplin added to the 1942 rerelease. Be sure to watch the original version. For a more serious take on the Klondike hardships, see Clarence Brown’s The Trail of ’98 (1928).

18. Short Term 12

Year: 2013

Director: Destin Daniel Cretton

Stars: Brie Larson, John Gallagher Jr., Kaitlyn Dever, Rami Malek, Alex Calloway, Lakeith Stanfield

Rating: R

As it progresses, Short Term 12 remains rigorously structured in terms of plot; yet it never feels calculated. In fact, the film serves as a fine example of how invisible screenwriting can be. By allowing his characters’ irrational emotions to influence events and instigate key turning points, Cretton capably masks the film’s finely calibrated story mechanics. And while everything seemingly comes to a head during a key crisis, it’s only fitting that the story ends with a denouement that bookends its opening. Cretton’s clear-eyed film is far too honest to try and convince us that there’s been any sort of profound change for Grace or anyone else. Instead, it’s content to serve as a potent reminder that tentative first steps can be every bit as narratively compelling as great leaps of faith. —Curtis Woloschuk

19. Let the Right One In

Year: 2008

Director: Tomas Alfredson

Stars: Kåre Hedebrant, Lina Leandersson, Per Ragnar, Ika Nord, Peter Carlberg

Rating: R

Vampires may have become cinema’s most overdone, watered-down horror villains, aside from zombies, but leave it to a Swedish novelist and filmmaker to reclaim frightening vampires by producing a novel and film that turned the entire genre on its head. Let the Right One In centers around the complicated friendship and quasi-romantic relationship between 12-year-old outcast Oskar and Eli, a centuries-old vampire trapped in the body of an androgynous (although ostensibly female) child who looks his same age. As Oskar slowly works his way into her life, drawing ever-closer to the role of a classical vampire’s human “familiar,” the film questions the nature of their bond and whether the two can ever possibly commune on a level of genuine love. At the same time, it’s also a chilling, very effective horror film whenever it chooses to be, especially in the absolutely spectacular final sequences, which evoke Eli’s terrifying abilities with just the right touch of obstruction to leave the worst of it in the viewer’s imagination. The film received an American remake in 2010, Let Me In, which has been somewhat unfairly derided by film fans sick of the remake game, but it’s another solid take on the same story that may even improve upon a few small aspects of the story. Ultimately, though, the Swedish original is still the superior film thanks to the strength of its two lead performers, who vault it up to become perhaps the best vampire movie ever made. —Jim Vorel

20. The Paper Tigers

Year: 2021

Director: Bao Tran

Stars: Alain Uy, Ron Yuan, Mykel Shannon Jenkins, Roger Yuan, Matthew Page, Jae Suh Park, Joziah Lagonoy

Rating: PG-13

When you’re a martial artist and your master dies under mysterious circumstances, you avenge their death. It’s what you do. It doesn’t matter if you’re a young man or if you’re firmly living that middle-aged life. Your teacher’s suspicious passing can’t go unanswered. So you grab your fellow disciples, put on your knee brace, pack a jar of IcyHot and a few Ibuprofen, and you put your nose to the ground looking for clues and for the culprit, even as your soft, sapped muscles cry out for a breather. That’s The Paper Tigers in short, a martial arts film from Bao Tran about the distance put between three men and their past glories by the rigors of their 40s. It’s about good old fashioned ass-whooping too, because a martial arts movie without ass-whoopings isn’t much of a movie at all. But Tran balances the meat of the genre (fight scenes) with potatoes (drama) plus a healthy dollop of spice (comedy), to similar effect as Stephen Chow in his own kung fu pastiches, a la Kung Fu Hustle and Shaolin Soccer, the latter being The Paper Tigers’ spiritual kin. Tran’s use of close-up cuts in his fight scenes helps give every punch and kick real impact. Amazing how showing the actor’s reactions to taking a fist to the face suddenly gives the action feeling and gravity, which in turn give the movie meaning to buttress its crowd-pleasing qualities. We need more movies like The Paper Tigers, movies that understand the joy of a well-orchestrated fight (and for that matter how to orchestrate a fight well), that celebrate the “art” in “martial arts” and that know how to make a bum knee into a killer running gag. The realness Tran weaves into his story is welcome, but the smart filmmaking is what makes The Paper Tigers a delight from start to finish.–Andy Crump

21. Shiva Baby

Year: 2022

Director: Emma Seligman

Stars: Rachel Sennott, Molly Gordon, Polly Draper, Fred Melamed, Danny Deferrari, Dianna Agron

Rating: NR

Marvelously uncomfortable and cringe-inducingly hilarious, Emma Seligman’s Shiva Baby rides a fine line between comedy and horror that perfectly suits its premise–and feels immediately in step with its protagonist, the college-aged Danielle. Played by actress/comedian Rachel Sennott, already messy-millennial royalty by virtue of her extremely online comic sensibility, Danielle is first glimpsed mid-tryst, an unconvincing orgasm closing out her perfunctory dirty talk (“Yeah, daddy”) before she dismounts and collects a wad of cash from the older Max (Danny Deferrari). Though it’s transactional, as any sugar relationship tends to be, Danielle seems open to discussing her nebulous career aspirations with Max, and he gives her an expensive bracelet–suggesting a quasi-intimate familiarity to their dynamic, even if the encounter’s underlying awkwardness keeps either from getting too comfortable. As such, it’s a smart tease of what’s to come, as Danielle schleps from Max’s apartment to meet up with her parents, Debbie (Polly Draper) and Joel (Fred Melamed, naturally), and sit shiva in the home of a family friend or relative. That Danielle’s unclear on who exactly died is a recurring joke, and a consistently good one, but there’s little time to figure out the details before she’s plunged into the event: A disorienting minefield of small talk, thin smiles and self-serve schmear. You don’t have to be Jewish to appreciate the high anxiety and mortifying comedy of Seligman’s film, though it helps. Underneath all the best Jewish punchlines lies a weary acknowledgement of inevitable suffering; the Coen Brothers knew this in crafting A Serious Man, their riotous retelling of the Book of Job, and Seligman knows it in Shiva Baby. That the climax involves shattered glass, helpless tears and a few humiliations more marks this as one of the most confidently, winningly Jewish comedies in years.–Isaac Feldberg

22. Children of the Mist

Year: 2022

Director: Ha Le Diem

Rating: NR

What’s most disturbing about Diem HÀ Lê’s directorial debut isn’t the subject matter but rather how nonchalantly it’s treated by those in front of her lens. Among the Hmong people of North Vietnam, it’s customary for young girls to be kidnapped from their homes, forced to become child brides for whomever steals them away. Children of the Mist’s bucolic setting—this mountain community feels like it exists in a mythic past—belies the Hmong’s cruel ritual, and the film focuses on 13-year-old Di, who fears that she could be the next target. But even her parents aren’t all that concerned—after all, it’s tradition—and Diem serves as a silent observer as the townspeople play kidnapping “games,” mocking the terror that awaits these girls. Children of the Mist is deceptively restrained in its first half, but that leads to a finale that’s raw in its pain and anguish. Few recent documentaries have captured anything so heart-wrenching as Di’s abduction, with Diem trying frantically to intervene, her camera recording every traumatizing moment. This is sobering filmmaking that illustrates a terrible injustice and the patriarchal attitudes that keep it thriving. —Tim Grierson

23. Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy

Year: 2021

Director: Ryusuke Hamaguchi

Stars: Kotone Furukawa, Ayumu Nakajima, Hyunri, Kiyohiko Shibukawa, Katsuki Mori, Shouma Kai, Fusako Urabe, Aoba Kawai

Rating: NR

The awkward charm of coincidental encounters is what sets Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy in motion, a collection of three short films about the unexpected outcomes of otherwise mundane interactions. Each segment lasts approximately 40 minutes, focusing on full-length casual conversations and the intense emotions they immediately provoke. The film’s anthology approach works as a compelling contrast to Hamaguchi’s other 2021 feature, Japan’s Oscar selection Drive My Car, which itself is a three-hour adaptation of Haruki Murakami’s short story of the same name. Whether by weaving together standalone shorts or fleshing out an existing text, the director suggests that the subtleties of everyday exchanges often harbor strange secrets. Though none of the stories are connected—or even exist in the same ostensible world—there is a consistent throughline of analyzing performance. Whether it’s achieved through a character playing out imagined scenarios in their mind, communicating the vulnerable passion of sex or roleplaying to receive long-awaited answers to unquelled questions, Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy demonstrates the benefit of inhabiting delusion. In fact, the film’s English-language title addresses this very fixation. The idea of fortune is not inherently bound to prosperity, but rather the more intangible and improbable intricacies of fated consequences. In this sense, the role of fantasy is to act as a salve for the often depressing mundanity of real-life obligations and social mores, whether through speculative daydreams, beguiling lies or invited deceit. Hamaguchi certainly possesses a fascination for depicting multifaceted women in his filmography (Happy Hour, Asako I & II and now Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy as well as Drive My Car), a trait that can surely be traced back to the filmmaker’s decades-long obsession with Cassavetes. This interest is compounded by his prominent focus on romance in women’s lives: In the case of Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy, these relationships range from doormat ex-boyfriends, unforeseen objects of seduction and long-lost loves. However, the women explored in each segment are hardly defined by their success in securing a happy union. Particularly due to the short films ranging from ending on a sour or slightly saccharine note, the characters are given much more room to be frustrated in their relationships—this theme of disharmony in otherwise functional relationships being another recurring motif in Hamaguchi’s films. Both Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy and Drive My Car incorporate themes of the erotic thrill of crafting a narrative, the power in playing pretend, and the malleable and ever-transmogrifying nature of human relationships. Though his highly anticipated Drive My Car distills these musings in a slightly more meticulous manner, Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy cuts to the chase in a way that’s quaintly quirky—and never dull to watch unfold.–Natalia Keogan

24. Alphaville

Year: 1965

Director: Jean-Luc Godard

Stars: Anna Karina, Eddie Constantine

Science-fiction isn’t particularly suited to Godard’s gaze—so erratic and tongue-in-cheek, so uninterested in the exigencies and peculiarities of world-building is the legendary French director—but there is also no better visionary to attack the mind-fuck that is this weirdo Lemmy Caution adventure. Alphaville is as much an experimental noir as it is speculative fiction, steeped in the tropes of the former while blissfully tinkering with the world of the latter, never quite justifying the hybridizing of both but never quite caring, either. As such, the pulpy story of a secret agent (Eddie Constantine) who’s sent into the “galaxy” of Alphaville to assassinate, amongst a few, the creator of the artificial intelligence (Alpha 60) which runs all facets of Alphavillian society by pretty much outlawing all emotion—meanwhile falling in love with the daughter of the inventor (Godard muse Anna Karina)—is as goofy as it is compelling, fully committed to the confusing premise and aware, as most Godard films are, of the leaps required of the audience to follow the meandering plot. Saturated with anachronism and stylized to the point of parody, Alphaville isn’t interested in immersing a viewer in a not-so-distant dystopian future as it is in laying bare science fiction as a genre which demands we dramatically re-conceptualize everything about the genre we take for granted: language, humanity and a future we’ll at least kind of understand. —Dom Sinacola

25. Neptune Frost

Year: 2022

Director: Saul Williams, Anisia Uzeyman

Stars: Cheryl Isheja, Elvis Ngabo, Diogene Ntarindwa

Neptune Frost is a powerful film, clean and digestible while it traffics in metaphors and deploys poetry and philosophy. Directed by Anisia Uzeyman (a Rwandan actress and playwright that also directed photography) and Saul Williams (an American musician and multimedia artist who also wrote the screenplay), Neptune Frost is extensively musical without ever being exhausting. It’s clear in its theses, demanding equity and decency for workers, for citizens of the Global South generally and Rwanda specifically, and for intersex and queer Africans subjected to discrimination and marginalization born from the same colonial traditions that rob nations of their wealth. It’s elegantly shot and engages with traditions of science fiction and anti-colonialist magical realism to frame an alternatingly rough and ornate Afrofuturist aesthetic. Calling Neptune Frost art with a purpose feels like damning it to the pile of things that are “good” because they are “important.” Neptune Frost is valuable because of the creative and organic way it delivers its messages: Questioning colonial legacies and demanding change through a moving, musical script while displaying speculative imagery that requires audiences’ imaginations as well as their eyeballs. Neptune Frost is about colonialism’s consequences–patriarchal heteronormativity, economic exploitation and resource extraction–punishing ignored masses. We need to pay attention; workers’ well-being is the price of our luxuries. In Rwanda, as in other parts of Africa, Asia, Oceania, South America and the Caribbean, the wealth of the West costs lives. But we’ve known this since Cien Años de Soledad, since Candide. It’s a reminder that there are no countries in Africa destined to be deprived of development, only countries who’ve had their wealth taken from and, often, weaponized against them. To that end, the poetry of the script, the clarity of the messages, the beauty of the music and the earnestness of the performances combine to make Neptune Frost a powerful film. Art can’t change the world on its own, but people—moving in solidarity and coalition, speaking up for and out against exploitation—can call upon one another to change it.–Kevin Fox, Jr.

26. Chile ’76

Year: 2023

Director: Manuela Martelli

Stars: Aline Küppenheim, Nicolás Sepúlveda, Hugo Medina, Alejandro Goic, Antonia Zegers, Marcial Tagle

Rating: NR

Decades after his death, Alfred Hitchcock’s name is still instinctively used to describe taut political thrillers like Manuela Martelli’s feature debut, Chile ’76. Set 3 years after Augusto Pinochet overthrew Salvador Allende, the film steeps in unease for 90 minutes; it’s the product of a nation contemporarily inclined toward fractured partisan politics, as if Martelli intends for her audience to face the historical rearview as a reminder of what happens to democracies when they catch a case of hyper-polarization. The first appropriate qualifier for Chile ’76 that anyone should reach for is “urgent.” But rather than “Hitchcockian,” the second qualifier should be “Pakulan.” Chile ’76 shares in common the same pliable atmospheric sensibility as the movies of Alan J. Pakula; Martelli roots her plot in realism one moment, then surrealism the next, oscillating between a sharp-lined authenticity and dreamlike paranoia. Martelli is an optimist, her belief being that when faced with incontrovertible proof of genuine government tyranny, the average citizen will do their part to buck the system even if it might mean getting disappeared by the bully president’s goon squad. The sensation of the film, on the other hand, is suspicion, the relentless and sickening notion that nobody can be trusted. Whether the thrumming electronic soundtrack or Soledad Rodríguez’s photography, composed to the point of feeling suffocating, Chile ’76 drives that anxiety like a knife in the heart.—Andy Crump

27. Shoplifters

Year: 2018

Director: Hirokazu Kore-eda

Stars: Lily Franky, Sakura Ando, Mayu Matsuoka, Kairi Jo, Miyu Sasaki, Kirin Kiki

Rating: R

The Shibatas—Osamu and Nobuyo (Lily Franky and Sakura Ando), daughter Aki (Mayu Matsuoka), son Shota (Kairi Jo) and grandma Hatsue (Kirin Kiri)—live in tight quarters together, their flat crowded and disheveled. Space is at a premium, and money’s tight. Osamu and Shota solve the latter problem by palming food from the local market, a delicately choreographed dance we see them perform in the film’s opening sequence: They walk from aisle to aisle, communicating to each other through hand gestures while running interference on market employees, a piano and percussion soundtrack painting a scene out of Ocean’s 11. It’s a heist of humble purpose. Once they finish, Shota having squirreled away sufficient goods in his backpack, father and son head home and stumble upon little Yuri (Miuy Sasaki) huddling in the cold on her parents’ deck. Osamu invites her over for dinner in spite of the Shibata’s meager circumstances. When he and Nobuyo go to return her to her folks later on, they hear sounds of violence from within their apartment and think better of it. So Yuri becomes the new addition to the Shibata household, a move suggesting a compassionate streak in Osamu that slowly crinkles about the edges as Shoplifters unfolds. The obvious care the Shibatas, or whoever they are, have for one another forestalls or at least deflects a building dread: Even in squalor, there’s a certain joy present in their situation. It’s not magic, per se—there’s nothing magical about poverty—but comfort, a sense of safety in numbers. But for a few stolen fishing rods, the Shibata clan is content with what it has, and Kore-eda asks us if that’s such a crime in a world both literally and figuratively cold to the plight of the unfortunate. Shoplifters is held up by the strength of its ensemble and Kore-eda’s gifts as a storyteller, which gain with every movie he makes. —Andy Crump

28. I Am Not Your Negro

Year: 2017

Director: Raoul Peck

Rating: PG-13

Raoul Peck focuses on James Baldwin’s unfinished book Remember This House, a work that would have memorialized three of his friends, Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X and Medgar Evers. All three black men were assassinated within five years of each other, and we learn in the film that Baldwin was not just concerned about these losses as terrible blows to the Civil Rights movement, but deeply cared for the wives and children of the men who were murdered. Baldwin’s overwhelming pain is as much the subject of the film as his intellect. And so I Am Not Your Negro is not just a portrait of an artist, but a portrait of mourning—what it looks, sounds and feels like to lose friends, and to do so with the whole world watching (and with so much of America refusing to understand how it happened, and why it will keep happening). Peck could have done little else besides give us this feeling, placing us squarely in the presence of Baldwin, and I Am Not Your Negro would have likely still been a success. His decision to steer away from the usual documentary format, where respected minds comment on a subject, creates a sense of intimacy difficult to inspire in films like this. The pleasure of sitting with Baldwin’s words, and his words alone, is exquisite. There’s no interpreter, no one to explain Baldwin but Baldwin—and this is how it should be. —Shannon M. Houston

29. It’s a Wonderful Life

Year: 1946

Director: Frank Capra

Stars: James Stewart, Donna Reed, Lionel Barrymore

Rating: PG

Frank Capra’s Christmas fantasy actually kind of flopped at the box office when it was released, and put Capra on the out-to-pasture list as the studio decided he was no longer capable of scoring a hit. Then it was nominated for five Academy Awards and has become known as one of the most acclaimed films ever made. On Christmas Eve, suicidal George Bailey (the sublime Jimmy Stewart) receives a visit from a sort of junior angel who calls himself Clarence Odbody (Henry Travers). Clarence is charged with pulling Bailey off the ledge, in return for which he will be granted wings. So he shows Bailey visions of his life, progressing from his childhood, showing Bailey all the times he made someone’s live better (or outright saved it). Ultimately Clarence jumps into the river before George can do it; activating the suicidal man to save Clarence rather than kill himself. It’s not enough, so Clarence shows him what the world would look like if he’d never been born. When George sees that his existence has had and continues to have a positive impact on the world, he goes home to his family, Clarence gets his wings and happiness ensues. Yup, it’s a Christmas story. And it’s one of the most enduring ones for a bunch of reasons, including Stewart’s amazing performance and a beautiful script by Frances Goodrich and Albert Hackett along with Capra. (Both Stewart and Capra commented that it was their favorite of all the films they’d respectively worked on.) Timeless, big-hearted and disarmingly sincere, this film is one I defy you to have one cynical comment about. Go on: be cynical. You can’t, right? Right. Because it’s not possible. —Amy Glynn

30. The Hunt

Year: 2012

Director: Thomas Vinterberg

Stars: Mads Mikkelsen, Thomas Bo Larsen, Susse Wold, Annika Wedderkopp

Rating: R

Thomas Vinterberg’s harrowing drama serves as a companion piece of sorts to the documentaries concerning the travails of the West Memphis Three. Whereas the non-fiction work of Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky (The Paradise Lost trilogy) and Amy Berg (West of Memphis) examined how deep-seated prejudice could spawn a protracted miscarriage of justice, Vinterberg’s nerve-fraying character study investigates the lingering ramifications of rash actions and rushes to judgement. But first, it sets a scene not all that unlike West Memphis, Arkansas. The Hunt unfolds in a small, rural community where the jocular men view each other as brothers and the children wander the streets unattended, their safety taken for granted. Our introduction to Lucas (Mads Mikkelsen) comes as he’s rescuing a burly, naked friend from a frigid lake. Rest assured, Lucas will suffer mightily because of Klara (Annika Wedderkopp), a little girl who has a crush on him. When he gently scolds her for being overly affectionate, she responds by intimating to another teacher that Lucas exposed himself. What follows is a witch-hunt that Denmark hasn’t seen the likes of since the reign of Christian IV. Vinterberg and co-writer Tobias Lindholm (A Hijacking) have no interest in detailing the legalities at play here. Instead, they’re fascinated with the way in which conservative communities are willing to close ranks at the slightest provocation. Brilliantly written and masterfully staged, the climax arrives with the entire town gathered in a warmly lit church on Christmas Eve. As Vinterberg allows the scene to methodically unfold, we watch Mikkelsen’s stony countenance become consumed with indignation. Even within the walls of an institution that hinges on blind faith, there’s not a single person who will give him the benefit of the doubt. The rank hypocrisy glimpsed in the sequence is galling. And yet, Vinterberg never allows his evident disdain for such flock mentalities to affect his steady directorial hand. Fittingly for a film that deals with actions that can’t be undone, The Hunt leaves you with a sickening feeling that’s almost impossible to shake. —Curtis Woloschuk

31. The Squid and the Whale

Year: 2005

Director: Noah Baumbach

Stars: Jeff Daniels, Laura Linney, Jesse Eisenberg, Owen Kline, Anna Paquin

Rating: R

Borrowing themes from his previous films—children of failed marriages; characters whose bookish smarts seem to work against them; a floating sense of fatalism—The Squid and the Whale creeps ever closer to Noah Baumbach’s own tempestuous past. His parents’ faltering union isn’t just a detail used to add depth to a certain character. It’s the whole story—a gorgeous, candid portrait of the messy car crash of divorce, from all angles. “It’s hard to even put myself in the mindset of those movies anymore,” he told Paste in 2005. “With Squid, these are reinventions of people that are close to me, and this is the movie I identify with the most. It is a natural extension of what I have intended and what I feel. I trusted myself more on this one.” —Keenan Mayo

32. The Look of Silence

Year: 2014

Director: Joshua Oppenheimer

Rating: PG-13

Like The Act of Killing, Joshua Oppenheimer’s companion film—the syntactically similar The Look of Silence—asks you to contemplate the literal meaning behind its title. Again returning to Indonesia, a country languishing in the anti-communist genocides of the 1960s, Oppenheimer this time sets his eye on Adi, a middle-aged optician whose brother was murdered by the men who were the focus of the first film, people today treated as local celebrities. Without question, the film is an interrogation of what it means to watch—as those who led the genocides; as those who are loved ones of those who led the genocides; as those who must repress the anger and humiliation of living beside such people every day; and, most palpably of all, as those of us who are distant observers, left with little choice but to witness such horror in the abstract. As in its predecessor, Oppenheimer’s patience and ability to acquaint himself intimately with the film’s subjects make for one gut-scraping scene after another—the sight of Adi’s 100+ year-old father, especially, is harrowing: blind and senile, the man is abjectly terrified as he scoots around on the floor, flailing and screaming that he’s trapped, having no idea where, or when, he is. Yet, moreso than in The Act of Killing, Oppenheimer here demands our undivided attention, forcing us to confront his quiet, sad documentary with the notion that seeing is more than believing—to see is to bear responsibility for the lives we watch. —D.S.

33. Another Round

Year: 2020

Director: Thomas Vinterberg

Stars: Mads Mikkelsen, Thomas Bo Larsen, Lars Ranthe, Magnus Millang

Rating: NR

In Thomas Vinterberg’s new film Another Round, camaraderie starts out as emotional support before dissolving into male foolishness cleverly disguised as scientific study: A drinking contest where nobody competes and everybody wins until they lose. Martin (Mads Mikkelsen), a teacher in Copenhagen, bobs lazily through his professional and personal lives: When he’s at school he’s indifferent and when he’s at home he’s practically alone. Martin’s closest connections are with his friends and fellow teachers, Tommy (Thomas Bo Larsen), Nikolaj (Magnus Millang) and Peter (Lars Ranthe), who like many dudes of a certain age share his glum sentiments. To cure their malaise, Nikolaj proposes putting Norwegian psychiatrist Finn Skårderud’s blood alcohol content theory to the test: Skårderud maintains that hovering at a cool 0.05% BAC helps people stay relaxed and loose, thus increasing their faculty for living to the fullest. As one of the day’s preeminent screen actors, Mikkelsen finds the sweet spot between regret and rejoicing, where his revelries are honest and true while still serving as covers for deeper misgivings and emotional rifts. Sorrow hangs around the edges of his eyes as surely as bliss spreads across his face with each occasion for drinking. That balancing act culminates in an explosive burst of anger and, ultimately, mourning. Good times are had and good times always end. What Another Round demonstrates right up to its ecstatic final moments, where Mikkelsen’s sudden and dazzling acrobatics remind the audience that before he was an actor he was a dancer and gymnast, is that good times are all part of our life cycle: They come and go, then come back again, and that’s better than living in the good times all the time. Without a pause we lose perspective on all else life has to offer, especially self-reflection. —Andy Crump

34. Memento

Year: 2000

Director: Christopher Nolan

Stars: Guy Pearce, Joe Pantoliano, Carrie-Anne Moss

Rating: R

During a brutal attack in which he believes his wife was raped and murdered, insurance-fraud investigator Leonard Shelby (played with unequivocal intensity, frustration and panic by Guy Pearce) suffers head trauma so severe it leads to his inability to retain new memories for more than a few minutes. This device allows Nolan to brilliantly deconstruct traditional cinematic storytelling, toggling between chronological black-and-white vignettes and full-color five-minute segments that unfold in reverse order while Pearce frantically searches for his wife’s killer. The film is jarring, inventive and adventurous, and the payoff is every bit worth the mind-bending descent into madness. —Steve LaBate

35. The Wrath of Becky

Year: 2023

Director: Matt Angel, Suzanne Coote

Stars: Lulu Wilson, Seann William Scott, Denise Burse, Jill Larson, Michael Sirow, Matt Angel, Aaron Dalla Villa, Courtney Gains, Kate Siegel

Rating: R

Clout-chasing tankie and dimwitted conspiracy theorist Jackson Hinkle declared this past April that “Gen Z is pro gun.” He was trying to be clever, and should’ve thought twice. Gen Z is demonstrably not pro gun, the only exception being one that proves the rule: Becky, Lulu Wilson’s mononymous psychopathic anti-hero protagonist of 2020’s Becky and its new follow-up, The Wrath of Becky. Becky loves guns, but mostly because they do handy work of blowing away white supremacists. Hinkle and Becky wouldn’t get along especially well. Granted, Becky doesn’t get along with anyone other than her Cane Corso pooch, Diego, and Elena (Denise Burse), her unofficial custodian and perhaps the only human worthy of her respect. The Wrath of Becky picks up a few steps ahead of where Becky left off, skipping past the police interrogation that concludes the latter to establish her as a ward of the state in the former. We don’t have data on how Zoomers feel about mindless ultraviolence, but the wholesale slaughter of hatemongers is a victimless crime, particularly when orchestrated with a total absence of pretense. Directors Matt Angel and Suzanne Coote, taking over for previous directors Jonathan Milott and Cary Murnion and tagging in with previous writer Nick Morris to co-write the sequel’s script, keep the premise simple: Fascists are horrible; let’s go kill ‘em all. The Wrath of Becky is “about” meaningful themes and ideas and events as a begrudging and unavoidable consequence of basing its heavies on the Proud Boys; it isn’t actually about anything other than the sheer titillating pleasure of watching the bad guys get dead. Nothin’ wrong with that! It’s built to thrill and made for chuckles, offset by Seann William Scott’s looming menace. Scott fulfills the same function as James in Becky: The funnyman stepping into the role of the heavy, uncovering the grim, callous side tucked in that persona. Wilson’s screen presence has expanded greatly since Becky, and her physicality matches her up well against Scott’s straight-faced intimidation. They’re a classic pairing, like the Road Runner and Wile E. Coyote, prey and predator in a reverse relationship: We know who’s supposed to be hunting who, but our expectations are continually upended with gory comedy. That The Wrath of Becky offers slapstick married with a kill tally and not much else is a feature, not a flaw.—Andy Crump