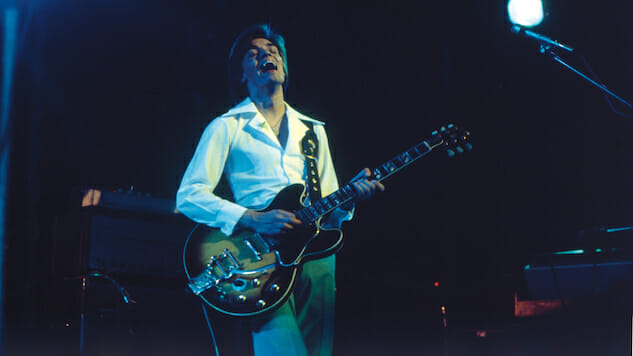

Bill Nelson Looks Back At The Making of Be-Bop Deluxe’s Sunburst Finish

Sunburst Finish, the 1976 album from art rock quartet Be-Bop Deluxe, falls into this valley set between the major musical movements in the band’s native England. Prog rock and proto-metal was on the wane with the rising signs of punk and post-punk about to dominate the cultural conversation. Like the lyric of the album’s hit single “Ships In The Night,” it felt like a square peg stuck in a cultural landscape of round holes.

Heard today, it feels like the perfect record for that time period. Singer/guitarist Bill Nelson adhered to a musical complexity that resulted in multi-tiered tunes like “Sleep That Burns,” which moves from ambling rock to cocktail jazz to full on bombast in a mere five minutes, and the searing rock of “Blazing Apostles” and the ether-drunk psychedelia of “Crying To The Sky.” Sunburst was a clearing of the decks before giving way to the dart-like directness that ripped through the English music scene just a year later.

Sunburst also represented the final metamorphosis of Be-Bop Deluxe as it introduced the band’s finest lineup that included keyboardist Andy Clarke, bassist Charlie Tumahai and drummer Simon Fox. They would carry the torch for this project forward for another two years before Nelson pulled the plug. It also carried some milestones for the band beyond their only charting single. For the first time, Nelson was allowed to control the mixing board with a great deal of help from John Leckie, the now legendary producer who got his first major co-production credit from these sessions.

This album has been fresh on the mind of longtime fans of Be-Bop Deluxe and new listeners thanks to a recent deluxe reissue of the album released by Cherry Red Records that marries a re-mastered version of the original recording with a new stereo mix, a batch of bonus tracks and radio sessions from the time. It’s a lovely package that does justice to an oft-overlooked album (at least here in the U.S.).

Paste recently spent a little time on the phone with the band’s leader Bill Nelson to talk about the making of Sunburst Finish, working with Leckie and how Be-Bop Deluxe changed with the arrival of Clarke and their arrival on the pop charts.

Paste: Listening to Sunburst Finish, I was taken by how many different styles of music you worked into these songs from rock to jazz to reggae and a bit of Latin influence. Was that pretty reflective of your listening habits at the time?

Bill Nelson: My listening, generally, is very eclectic. I listen to all kinds of music. I listen to a lot of jazz, classical, pop, rock, avant garde music. It all tends to leak into the songwriting process in some ways.

Do you have a sense of what you were listening to back then?

I’ve got a vast record collection and even back then it was pretty large. Back then, I was listening to Steely Dan, Frank Zappa, Jackson Browne, Neil Young. Loads of different people.

You’ve talked about how you presented the rest of the band with fairly complete demos for the tracks that would end up on Sunburst. Was that something that was welcomed by the other guys in the group or was there any pushback or any friction about not having their songs in the mix?

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-