The Best Albums of 1981

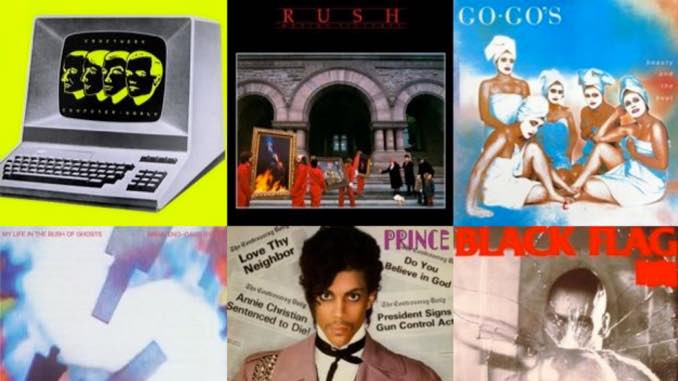

I was nine years old in 1981 when I purchased my first cassette, Beauty and the Beat by The Go-Go’s. It wouldn’t be the last seven dollars I’d spend on music, but it was a good start. It was also a good line of demarcation between by older brother’s vinyl featuring lots of Beach Boys and Eagles albums and the post-punk and New Wave that would help define the early ’80s. Of course, there was great music coming from all corners in 1981, from progressive rock to progressive soul to avant garde electronic music—it was a surprisingly opportune time for experimentation. The Paste music staff and writers voted on their favorites from 40 years ago, and here are the 25 Best Albums of 1981.

25. Killing Joke: What’s THIS For…! There has always been something angular and mechanical about Killing Joke, as if their dark, frantic tunes were meant to be the workplace soundtrack for our future robot overlords. As much post-metal as post-rock, the English quartet (now quintet) laid the groundwork for an industrial music revolution. The real genius here is the human emotion that comes through such spare efficiency. The album’s single is driven by Paul Ferguson’s machine-gun drumming, while Jaz Coleman repeats the ironic mantra “Follow the leaders / Look at the leaders.” —Josh Jackson

There has always been something angular and mechanical about Killing Joke, as if their dark, frantic tunes were meant to be the workplace soundtrack for our future robot overlords. As much post-metal as post-rock, the English quartet (now quintet) laid the groundwork for an industrial music revolution. The real genius here is the human emotion that comes through such spare efficiency. The album’s single is driven by Paul Ferguson’s machine-gun drumming, while Jaz Coleman repeats the ironic mantra “Follow the leaders / Look at the leaders.” —Josh Jackson

24. Grace Jones: Nightclubbing Grace Jones’ fifth studio album, Nightclubbing is just as musically multifaceted as it is visually. The album’s melding of left-field pop, New Wave, reggae, dance-pop and funk sent a shockwave through the music world, and it was unbelievably cohesive, stark and burly. The album cover didn’t need to do much work because Jones is a literal walking piece of cubist art. Her sound and image is as majestic as it is threatening. And the title track, a cover from Iggy Pop’s 1977 solo debut, improves upon the original. After all, it’s not Iggy Pop who’s emblematic of the most famous nightclub of all time. But the brooding, minimalist track inherently lacks the sheen of Studio 54, and on all of Nightclubbing, Jones was actively stepping away from disco—associating the radical avant-garde artist with only that era is extremely reductive, really. Her signature deadpan offers a stylish, restrained departure from the dialed-down but ever-present grit of the original. Jones’ take, with the dub-leaning reggae of Compass Point All-Stars as its bedrock, feels totally organic. —Lizzie Manno and Jhoni Jackson

Grace Jones’ fifth studio album, Nightclubbing is just as musically multifaceted as it is visually. The album’s melding of left-field pop, New Wave, reggae, dance-pop and funk sent a shockwave through the music world, and it was unbelievably cohesive, stark and burly. The album cover didn’t need to do much work because Jones is a literal walking piece of cubist art. Her sound and image is as majestic as it is threatening. And the title track, a cover from Iggy Pop’s 1977 solo debut, improves upon the original. After all, it’s not Iggy Pop who’s emblematic of the most famous nightclub of all time. But the brooding, minimalist track inherently lacks the sheen of Studio 54, and on all of Nightclubbing, Jones was actively stepping away from disco—associating the radical avant-garde artist with only that era is extremely reductive, really. Her signature deadpan offers a stylish, restrained departure from the dialed-down but ever-present grit of the original. Jones’ take, with the dub-leaning reggae of Compass Point All-Stars as its bedrock, feels totally organic. —Lizzie Manno and Jhoni Jackson

23. The Human League: Dare! The Human League’s third record sold loads of copies due to the massive success of the single “Don’t You Want Me,” which you simply couldn’t escape in 1982. The band’s music relied heavily on synthesizers, but it was Dare where their more avant proclivities met with pop and even elements of Bowie-esque glam. But not everything on the record is as immediately catchy as “Don’t You Want Me.” “Seconds” is dark and moody and “Do Or Die,” even with its synth hook, is still elegant and nuanced. Dare was a huge hit for The Human League, but it also remains a forward-thinking record that has aged better than most. —Mark Lore

The Human League’s third record sold loads of copies due to the massive success of the single “Don’t You Want Me,” which you simply couldn’t escape in 1982. The band’s music relied heavily on synthesizers, but it was Dare where their more avant proclivities met with pop and even elements of Bowie-esque glam. But not everything on the record is as immediately catchy as “Don’t You Want Me.” “Seconds” is dark and moody and “Do Or Die,” even with its synth hook, is still elegant and nuanced. Dare was a huge hit for The Human League, but it also remains a forward-thinking record that has aged better than most. —Mark Lore

22. Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark: Architecture and Morality OMD may be best-known by many from providing the soundtrack to an iconic moment in a John Hughes film, but their early work is a far cry from Pretty in Pink’s “If You Leave.” The group from Mercyside, England, were synth-pop pioneers who paved the way for bands like Depeche Mode, New Order, Joy Division and Tears for Fears, despite not always receiving the same love from the British press. Songs like “She’s Leaving” off Architecture and Morality deliver the kind of beautiful trance-inducing moments other bands continue to strive for thanks to its bouncing keyboard melodies and counter-melodies (three of OMD’s four members played synths on the album), along with choral samples inspired by high-church hymns. Singles “Souvenir,” “Joan of Arc” and “Maid of Orleans” all reached the Top 5 on the UK charts, helping the album sell four million copies worldwide. —Josh Jackson

OMD may be best-known by many from providing the soundtrack to an iconic moment in a John Hughes film, but their early work is a far cry from Pretty in Pink’s “If You Leave.” The group from Mercyside, England, were synth-pop pioneers who paved the way for bands like Depeche Mode, New Order, Joy Division and Tears for Fears, despite not always receiving the same love from the British press. Songs like “She’s Leaving” off Architecture and Morality deliver the kind of beautiful trance-inducing moments other bands continue to strive for thanks to its bouncing keyboard melodies and counter-melodies (three of OMD’s four members played synths on the album), along with choral samples inspired by high-church hymns. Singles “Souvenir,” “Joan of Arc” and “Maid of Orleans” all reached the Top 5 on the UK charts, helping the album sell four million copies worldwide. —Josh Jackson

21. The Blasters: The Blasters This Southern California band’s second album was their first with national distribution, and its blues-drenched rockabilly was an astonishing wake-up call for the rest of the country. Dave Alvin wrote the originals, and his older brother Phil sang them—a smart and effective division of labor. The tight rhythm section was supplemented by a horn section of Fats Domino’s legendary Lee Allen and future Los Lobos member Steve Berlin. “Marie Marie” became a top-20 single in England for Shakin’ Stevens, and rocking anthems such as “Border Radio” and “American Music” became highlights of the Blasters’ dazzling live shows. These aren’t Dave Alvin’s best songs, but they are his songs easiest to like on a first listen. —Geoffrey Himes

This Southern California band’s second album was their first with national distribution, and its blues-drenched rockabilly was an astonishing wake-up call for the rest of the country. Dave Alvin wrote the originals, and his older brother Phil sang them—a smart and effective division of labor. The tight rhythm section was supplemented by a horn section of Fats Domino’s legendary Lee Allen and future Los Lobos member Steve Berlin. “Marie Marie” became a top-20 single in England for Shakin’ Stevens, and rocking anthems such as “Border Radio” and “American Music” became highlights of the Blasters’ dazzling live shows. These aren’t Dave Alvin’s best songs, but they are his songs easiest to like on a first listen. —Geoffrey Himes

20. Marvin Gaye: In Our Lifetime It’s sometimes lost in the shadow of Midnight Love—which holds the distinction of being both Marvin Gaye’s biggest-selling and final album—but In Our Lifetime is secretly the better of Gaye’s two late-career records. By the start of the ’80s, Gaye had suffered a mountain of hardships in just a few years: a bitter divorce, a ruinous cocaine addiction, an aborted album called Love Man, and a 1979 suicide attempt. In Our Lifetime was both a kind of rebirth and an ending, since it proved to be Gaye’s last record for Motown. Gaye flirts with the burgeoning rap movement on “In Our Lifetime” and “Ego Tripping Out” (a holdover from Love Man, included only on the CD rerelease) and delivers one of his most brooding, tragic meditations on lost love with “Heavy Love Affair.” Unlike the synth-heavy Midnight Love, this album works as a slyly funky, revved-up throwback to the sensual feel of 1976’s I Want You. —Zach Schonfeld

It’s sometimes lost in the shadow of Midnight Love—which holds the distinction of being both Marvin Gaye’s biggest-selling and final album—but In Our Lifetime is secretly the better of Gaye’s two late-career records. By the start of the ’80s, Gaye had suffered a mountain of hardships in just a few years: a bitter divorce, a ruinous cocaine addiction, an aborted album called Love Man, and a 1979 suicide attempt. In Our Lifetime was both a kind of rebirth and an ending, since it proved to be Gaye’s last record for Motown. Gaye flirts with the burgeoning rap movement on “In Our Lifetime” and “Ego Tripping Out” (a holdover from Love Man, included only on the CD rerelease) and delivers one of his most brooding, tragic meditations on lost love with “Heavy Love Affair.” Unlike the synth-heavy Midnight Love, this album works as a slyly funky, revved-up throwback to the sensual feel of 1976’s I Want You. —Zach Schonfeld

19. Rosanne Cash: Seven Year Ache The title track may be Cash’s finest moment: the confession of a woman who still loves the man she’s furious with, a contradiction given an elegant melody, a moody arrangement, and a brilliant vocal that communicates several feelings at once. The other Cash composition, “Blue Moon with Heartache,” was also a #1 country single. The other songs by producer Rodney Crowell, Keith Sykes, Merle Haggard, Sonny Curtis, Steve Forbert, Tom Petty, and Leroy Preston showcase Cash’s skill at either sassy pop-rock or traditional country. Johnny’s daughter was at her best, though, when she blended the two, and the title track became the model for the triumphs ahead. —Geoffrey Himes

The title track may be Cash’s finest moment: the confession of a woman who still loves the man she’s furious with, a contradiction given an elegant melody, a moody arrangement, and a brilliant vocal that communicates several feelings at once. The other Cash composition, “Blue Moon with Heartache,” was also a #1 country single. The other songs by producer Rodney Crowell, Keith Sykes, Merle Haggard, Sonny Curtis, Steve Forbert, Tom Petty, and Leroy Preston showcase Cash’s skill at either sassy pop-rock or traditional country. Johnny’s daughter was at her best, though, when she blended the two, and the title track became the model for the triumphs ahead. —Geoffrey Himes

18. The Cure: Faith The Cure became The Cure as we now know them on their third album Faith, blackening their pop-rock and post-punk sounds, and growing ever more morbid and dour while retaining the melodies that had begun to make them world-famous. Though the band would descend even deeper into downcast gothic rock on Pornography the following year, Faith remains an emotionally suffocating listen—you can’t help but “feel [your] heart pushed in,” as Robert Smith sings on sepulchral opener “The Holy Hour.” The album’s bleak, looming beauty is perhaps best exemplified by “The Funeral Party,” which Smith opens on the image of “Two pale figures / Ache in silence / Timeless / In the quiet ground,” his ghostly moans hanging over luminous synth swells—the transition into the subsequent track, the aggressive, surf rock-tinged “Doubt,” is jarring in the best way. Even The Cure themselves were not immune to Faith’s emotional drain: “Those songs had a downward spiral effect on us—the more we played them, the more despondent and desolate we became,” Smith would later say; he was known to leave the stage in tears during the Faith era. That speaks to The Cure’s commitment to their art, but also to the power of the songs themselves—enough to shatter your heart and build a new, darker heart in its place. —Scott Russell

The Cure became The Cure as we now know them on their third album Faith, blackening their pop-rock and post-punk sounds, and growing ever more morbid and dour while retaining the melodies that had begun to make them world-famous. Though the band would descend even deeper into downcast gothic rock on Pornography the following year, Faith remains an emotionally suffocating listen—you can’t help but “feel [your] heart pushed in,” as Robert Smith sings on sepulchral opener “The Holy Hour.” The album’s bleak, looming beauty is perhaps best exemplified by “The Funeral Party,” which Smith opens on the image of “Two pale figures / Ache in silence / Timeless / In the quiet ground,” his ghostly moans hanging over luminous synth swells—the transition into the subsequent track, the aggressive, surf rock-tinged “Doubt,” is jarring in the best way. Even The Cure themselves were not immune to Faith’s emotional drain: “Those songs had a downward spiral effect on us—the more we played them, the more despondent and desolate we became,” Smith would later say; he was known to leave the stage in tears during the Faith era. That speaks to The Cure’s commitment to their art, but also to the power of the songs themselves—enough to shatter your heart and build a new, darker heart in its place. —Scott Russell

17. The Replacements: Sorry Ma, Forgot to Take Out the Trash As if to fulfill some ancient musical prophecy, The Replacements were delivered in a weird twist on the virgin birth: shot naked, motherless and screaming from the defiantly extended middle finger of Johnny Cash and straight into this world, charged with the high-holy task of unconsciously saving rock ’n’ roll from itself and all its bloated high-art pretension. Of course, they didn’t seem like heroes at first. Their speed-punk debut Sorry Ma, Forgot to Take Out the Trash sounds culled from the same lo-fi/high-energy of Hüsker Dü. They were just a bunch of regular-looking drunks from Minneapolis—not perfectly coiffed stadium-rock virtuosos or fashion-obsessed art rockers from some preordained center of cool like L.A. or New York. They were everyday fellas who, together, beat the odds every so often, reaching greatness far beyond their means: underachievers overachieving, real people (who could’ve been me or you or anyone else if we’d had the guts); a band surviving on momentum, spilled beer and underdog charm. —Steve LaBate

As if to fulfill some ancient musical prophecy, The Replacements were delivered in a weird twist on the virgin birth: shot naked, motherless and screaming from the defiantly extended middle finger of Johnny Cash and straight into this world, charged with the high-holy task of unconsciously saving rock ’n’ roll from itself and all its bloated high-art pretension. Of course, they didn’t seem like heroes at first. Their speed-punk debut Sorry Ma, Forgot to Take Out the Trash sounds culled from the same lo-fi/high-energy of Hüsker Dü. They were just a bunch of regular-looking drunks from Minneapolis—not perfectly coiffed stadium-rock virtuosos or fashion-obsessed art rockers from some preordained center of cool like L.A. or New York. They were everyday fellas who, together, beat the odds every so often, reaching greatness far beyond their means: underachievers overachieving, real people (who could’ve been me or you or anyone else if we’d had the guts); a band surviving on momentum, spilled beer and underdog charm. —Steve LaBate

16. Squeeze: East Side Story By 1981, Squeeze had three progressively better-selling albums under their belt, and songwriting partners Chris Difford and Glen Tilbrook were building a budding career as New Wave tunesmiths with hits like “Pulling Mussels (From the Shell)” and “Another Nail in My Heart”—but they chucked all that for their fourth release, adding keyboardist/blue-eyed soul singer Paul Carrack to the lineup and working with Elvis Costello and pub rockers Dave Edmunds and Nick Lowe on the sessions for “East Side Story.” The result was one of their most consistent albums—smoothly polished, but not lacking for sonic warmth, and boasting arguably the band’s definitive hit, the Carrack-sung “Tempted.” Unfortunately, “Story” wasn’t quite the gateway to greater success that it sounded like at the time—in fact, it presaged a period of massive turnover and generally declining commercial success—but for fans of Difford and Tilbrook’s indelible melodies and rueful, acerbic humor, it remains a high point. —Jeff Giles

By 1981, Squeeze had three progressively better-selling albums under their belt, and songwriting partners Chris Difford and Glen Tilbrook were building a budding career as New Wave tunesmiths with hits like “Pulling Mussels (From the Shell)” and “Another Nail in My Heart”—but they chucked all that for their fourth release, adding keyboardist/blue-eyed soul singer Paul Carrack to the lineup and working with Elvis Costello and pub rockers Dave Edmunds and Nick Lowe on the sessions for “East Side Story.” The result was one of their most consistent albums—smoothly polished, but not lacking for sonic warmth, and boasting arguably the band’s definitive hit, the Carrack-sung “Tempted.” Unfortunately, “Story” wasn’t quite the gateway to greater success that it sounded like at the time—in fact, it presaged a period of massive turnover and generally declining commercial success—but for fans of Difford and Tilbrook’s indelible melodies and rueful, acerbic humor, it remains a high point. —Jeff Giles

15. Japan: Tin Drum On Tin Drum, Japan’s fifth and final LP, the British band adds a layer of worldliness to their lush art-pop, immersing themselves in Asian instrumentation (Chinese reed instrument suona) and imagery (“Visions of China”). Following the departure of guitarist Rob Dean, Japan secured more sonic space to indulge their experimental whims—from the digital landscapes of UK hit “Ghost” to the Far East textures of “Canton.” Throughout, David Sylvian’s warbled, post-Bryan Ferry croon slithers around Mick Karn’s purring fretless bass and Richard Barbieri’s textured keys—a combination both soothing and unsettling. —Ryan Reed

On Tin Drum, Japan’s fifth and final LP, the British band adds a layer of worldliness to their lush art-pop, immersing themselves in Asian instrumentation (Chinese reed instrument suona) and imagery (“Visions of China”). Following the departure of guitarist Rob Dean, Japan secured more sonic space to indulge their experimental whims—from the digital landscapes of UK hit “Ghost” to the Far East textures of “Canton.” Throughout, David Sylvian’s warbled, post-Bryan Ferry croon slithers around Mick Karn’s purring fretless bass and Richard Barbieri’s textured keys—a combination both soothing and unsettling. —Ryan Reed

14. Siouxsie and the Banshees: Juju Siouxsie Sioux started playing music in the punk anarchy of the Sex Pistols’ 1970s, but when she invited Magazine guitarist John McGeoch into her band, Goth pioneers Siouxsie and the Banshees helped create a whole new sound. It came together on 1980’s Juju, a dark concept record that ditched electronic sounds for McGeoch’s foreboding guitars. Together with Budgie’s punishing drums and Steven Severin’s frenetic bass, they created the perfect bed for Siouxsie’s lovely, haunting vocals. Who knew black magic could be so beautiful? —Josh Jackson

Siouxsie Sioux started playing music in the punk anarchy of the Sex Pistols’ 1970s, but when she invited Magazine guitarist John McGeoch into her band, Goth pioneers Siouxsie and the Banshees helped create a whole new sound. It came together on 1980’s Juju, a dark concept record that ditched electronic sounds for McGeoch’s foreboding guitars. Together with Budgie’s punishing drums and Steven Severin’s frenetic bass, they created the perfect bed for Siouxsie’s lovely, haunting vocals. Who knew black magic could be so beautiful? —Josh Jackson

13. The Fall: Slates This mini-album by The Fall captures everything that made the band so powerful and groundbreaking, while hinting at a more tuneful side that they would gradually embrace throughout the ’80s. On one end you have “Prole Art Threat,” an abrasive noise bomb of atonal guitar scrapes and jackhammer drums and Mark E. Smith’s contemptuous rant about condescending attitudes towards the working class. On the other there’s “Leave the Capitol,” perhaps the catchiest and least abrasive song the band had yet recorded; I’m guessing Smith wanted less adventurous listeners to hear the song’s eternally relevant message about how much London sucks. It’s not quite 25 minutes long, but it might be the best single record The Fall put out in its 40 year history. —Garrett Martin

This mini-album by The Fall captures everything that made the band so powerful and groundbreaking, while hinting at a more tuneful side that they would gradually embrace throughout the ’80s. On one end you have “Prole Art Threat,” an abrasive noise bomb of atonal guitar scrapes and jackhammer drums and Mark E. Smith’s contemptuous rant about condescending attitudes towards the working class. On the other there’s “Leave the Capitol,” perhaps the catchiest and least abrasive song the band had yet recorded; I’m guessing Smith wanted less adventurous listeners to hear the song’s eternally relevant message about how much London sucks. It’s not quite 25 minutes long, but it might be the best single record The Fall put out in its 40 year history. —Garrett Martin

12. The Police: Ghost in the Machine There are albums that envelope you in an ambience so unlike anything else you’ve ever heard that listening to them is like taking a trip to another world. Ghost in the Machine stands as a textbook case of that kind of experience. The Police broke the mold with their own unique sound pretty much right out of the gate, and all they did was keep upping the ante from there. In truth, all their albums stand apart from the rest in crucial ways, but Ghost in the Machine is arguably the one point in their catalog where the production/mix (crisp yet dense) plays as prominent a role as the songs do. It’s well-documented that the fault lines in the band’s internal dynamic were beginning to reach critical stress levels when drummer Stewart Copeland, guitarist Andy Summers and bassist/frontman Sting converged on AIR studio on the island of Montserrat to record their fourth album. By that time, Sting had come to dominate the creative process, ultimately getting his way in his push for a broader palette of keyboards and horns to augment the main foundation of drums, guitar, bass and vocals. Strangely, though, The Police emerged with the most sonically unified work of their career, a seamless and revolutionary integration of reggae into their sound that, like Talking Heads and Peter Gabriel, established a futurist vision of pop that could absorb sounds from all over the world. In some ways, pop music has operated from the same premise ever since. —Saby Reyes-Kulkarni

There are albums that envelope you in an ambience so unlike anything else you’ve ever heard that listening to them is like taking a trip to another world. Ghost in the Machine stands as a textbook case of that kind of experience. The Police broke the mold with their own unique sound pretty much right out of the gate, and all they did was keep upping the ante from there. In truth, all their albums stand apart from the rest in crucial ways, but Ghost in the Machine is arguably the one point in their catalog where the production/mix (crisp yet dense) plays as prominent a role as the songs do. It’s well-documented that the fault lines in the band’s internal dynamic were beginning to reach critical stress levels when drummer Stewart Copeland, guitarist Andy Summers and bassist/frontman Sting converged on AIR studio on the island of Montserrat to record their fourth album. By that time, Sting had come to dominate the creative process, ultimately getting his way in his push for a broader palette of keyboards and horns to augment the main foundation of drums, guitar, bass and vocals. Strangely, though, The Police emerged with the most sonically unified work of their career, a seamless and revolutionary integration of reggae into their sound that, like Talking Heads and Peter Gabriel, established a futurist vision of pop that could absorb sounds from all over the world. In some ways, pop music has operated from the same premise ever since. —Saby Reyes-Kulkarni

11. The Rolling Stones: Tattoo You Almost two years into the ’80s, the Rolling Stones were able to resurrect some of their mid-’70s vibes with Tattoo You, the 18th Stones full-length released in the States and 16th released in the UK. Like Zeppelin’s Physical Graffiti, Tattoo You was mostly assembled from recordings that had been sitting for years—a hodgepodge of literal leftovers that somehow gel into one of the band’s most canonical works. Arriving between 1980’s Emotional Rescue and 1983’s Undercover, Tattoo You helped extend the shelf life of the vintage Stones sound at a time when the band was beginning to explore stylistic avenues like disco and pop in an attempt to keep up with rapid changes in the musical landscape. Looking back, tunes like “Neighbors” and “Hang Fire” wouldn’t sound out of place alongside the likes of Billy Idol or Loverboy, but Keith Richards’ guitar reverberating into the air at the beginning of “Start Me Up” remains one of the most recognizable hooks in rock history. And you just don’t get a more quintessential example of what made Richards and drummer Charlie Watts’ connection so distinctive than the song “Slave.” Gurgling organs and tinkling pianos courtesy of Billy Preston, Nicky Hopkins and Ian Stewart (along with saxophone solos from none other than jazz giant Sonny Rollins) also contribute to what is arguably the Stones’ last-ever classic. —Saby Reyes-Kulkarni

Almost two years into the ’80s, the Rolling Stones were able to resurrect some of their mid-’70s vibes with Tattoo You, the 18th Stones full-length released in the States and 16th released in the UK. Like Zeppelin’s Physical Graffiti, Tattoo You was mostly assembled from recordings that had been sitting for years—a hodgepodge of literal leftovers that somehow gel into one of the band’s most canonical works. Arriving between 1980’s Emotional Rescue and 1983’s Undercover, Tattoo You helped extend the shelf life of the vintage Stones sound at a time when the band was beginning to explore stylistic avenues like disco and pop in an attempt to keep up with rapid changes in the musical landscape. Looking back, tunes like “Neighbors” and “Hang Fire” wouldn’t sound out of place alongside the likes of Billy Idol or Loverboy, but Keith Richards’ guitar reverberating into the air at the beginning of “Start Me Up” remains one of the most recognizable hooks in rock history. And you just don’t get a more quintessential example of what made Richards and drummer Charlie Watts’ connection so distinctive than the song “Slave.” Gurgling organs and tinkling pianos courtesy of Billy Preston, Nicky Hopkins and Ian Stewart (along with saxophone solos from none other than jazz giant Sonny Rollins) also contribute to what is arguably the Stones’ last-ever classic. —Saby Reyes-Kulkarni

10. The Birthday Party: Prayers on Fire The world first encountered Nick Cave’s junkie vampire schtick through the Birthday Party, the nihilistic post-punk band he formed in Melbourne with Mick Harvey, Phil Calvert, Tracy Pew and Rowland S. Howard. Their first full-length Prayers on Fire is almost oppressively dark, with the only relief from Cave’s perverse lyrics coming from his own guttural whelps and moans. Meanwhile the thudding rhythms of Calvert and Pew add a firm spine for Howard and Harvey to mold their guitar scrapes and organ buzz around. Prayers on Fire takes the challenging sound of the Pop Group and PiL’s Metal Box and turns it into something even darker and more disturbing.—Garrett Martin

The world first encountered Nick Cave’s junkie vampire schtick through the Birthday Party, the nihilistic post-punk band he formed in Melbourne with Mick Harvey, Phil Calvert, Tracy Pew and Rowland S. Howard. Their first full-length Prayers on Fire is almost oppressively dark, with the only relief from Cave’s perverse lyrics coming from his own guttural whelps and moans. Meanwhile the thudding rhythms of Calvert and Pew add a firm spine for Howard and Harvey to mold their guitar scrapes and organ buzz around. Prayers on Fire takes the challenging sound of the Pop Group and PiL’s Metal Box and turns it into something even darker and more disturbing.—Garrett Martin

9. The dB’s: Stands For Decibels Two years before R.E.M. released Murmur and three years after Big Star’s Third/Sister Lover, Peter Holsapple and Chris Stamey continued the tradition of Southern jangly guitar rock with their Winston/Salem, N.C. outfit The dB’s. Stamey had played bass with Alex Chilton, but the combination of Stamey and Holsapple produced something equally Byrds-influenced with lovely harmonies, tight rhythm and punchy power-pop hooks. —Josh Jackson

Two years before R.E.M. released Murmur and three years after Big Star’s Third/Sister Lover, Peter Holsapple and Chris Stamey continued the tradition of Southern jangly guitar rock with their Winston/Salem, N.C. outfit The dB’s. Stamey had played bass with Alex Chilton, but the combination of Stamey and Holsapple produced something equally Byrds-influenced with lovely harmonies, tight rhythm and punchy power-pop hooks. —Josh Jackson

8. The Go-Go’s: Beauty and the Beat Artists like Best Coast’s Bethany Cosentino, Jenny Lewis and La Sera’s Katy Goodman make the Go-Go’s’ Beauty and the Beat sound surprisingly contempo. The group’s debut album proved not only that they could make a consistent, perky sound that made room for several hit singles, but that they would leave a lasting impression on girl groups everywhere. “We Got The Beat,” “Our Lips Are Sealed” and “How Much More” deliver on the sunny, infectious hooks that make this group so approachable, while “Lust to Love” and “This Town” hit on intricate harmonies and refreshing arrangement. —Annie Black

Artists like Best Coast’s Bethany Cosentino, Jenny Lewis and La Sera’s Katy Goodman make the Go-Go’s’ Beauty and the Beat sound surprisingly contempo. The group’s debut album proved not only that they could make a consistent, perky sound that made room for several hit singles, but that they would leave a lasting impression on girl groups everywhere. “We Got The Beat,” “Our Lips Are Sealed” and “How Much More” deliver on the sunny, infectious hooks that make this group so approachable, while “Lust to Love” and “This Town” hit on intricate harmonies and refreshing arrangement. —Annie Black

7. U2: October October was a stepping stone for U2. Coming between the Irish band’s 1980 debut Boy and their 1983 breakthrough War, October found the group exploring religion and spirituality—recurring themes in U2’s career—and honing a musical approach that more fully blossomed on War. Yet the second album from Bono & Co. still resonates. The singles “Fire” and “Gloria” are the work of a band finding the sound that made it one of the biggest acts in the world. “I Threw a Brick Through a Window” foreshadowed the searching tone of later work and “With a Shout (Jerusalem)” paired The Edge’s piercing guitar with the thrumming rhythm that became a U2 trademark. Even as they were building a sound and identity, the foursome was still willing to play against type on the title track, putting Bono’s yearning vocals over a melancholy piano part played by The Edge. Though U2 reached greater heights, they wouldn’t have gotten there without October. —Eric R. Danton

October was a stepping stone for U2. Coming between the Irish band’s 1980 debut Boy and their 1983 breakthrough War, October found the group exploring religion and spirituality—recurring themes in U2’s career—and honing a musical approach that more fully blossomed on War. Yet the second album from Bono & Co. still resonates. The singles “Fire” and “Gloria” are the work of a band finding the sound that made it one of the biggest acts in the world. “I Threw a Brick Through a Window” foreshadowed the searching tone of later work and “With a Shout (Jerusalem)” paired The Edge’s piercing guitar with the thrumming rhythm that became a U2 trademark. Even as they were building a sound and identity, the foursome was still willing to play against type on the title track, putting Bono’s yearning vocals over a melancholy piano part played by The Edge. Though U2 reached greater heights, they wouldn’t have gotten there without October. —Eric R. Danton

6. Black Flag: Damaged In the ’80s, Black Flag’s cathartic, throat-shredding take on punk rock was unrivaled on the touring circuit. Fronted by the restless newcomer Henry Rollins—the band’s third frontman—the 1981 LP debut laid the ground rules for hardcore punk for decades to come. Bandleader Greg Ginn’s impossibly distorted and speedy guitar work is at its best on “Rise Above” and “Life of Pain.” The album also includes essential tracks like “Gimmie Gimmie Gimmie” and “TV Party. ” —Tyler Kane

In the ’80s, Black Flag’s cathartic, throat-shredding take on punk rock was unrivaled on the touring circuit. Fronted by the restless newcomer Henry Rollins—the band’s third frontman—the 1981 LP debut laid the ground rules for hardcore punk for decades to come. Bandleader Greg Ginn’s impossibly distorted and speedy guitar work is at its best on “Rise Above” and “Life of Pain.” The album also includes essential tracks like “Gimmie Gimmie Gimmie” and “TV Party. ” —Tyler Kane

5. Prince: Controversy The album was called Controversy and 23-year-old Prince was ready to cause a lot of it, from the Lord’s Prayer he coyly recites in the middle of the title track to the Reagan-baiting “Ronnie, Talk to Russia” and gleefully perverted “Jack U Off.” If on Dirty Mind sex was a compulsion, on Controversy it’s a full-blown ideology, one that revels in promises of sexual revolution and euphoric battle chants (“People call me rude / I wish we all were nude,” etc). The Purple One continued to write, produce, and perform nearly every instrument himself, expanding the parameters of Dirty Mind’s synth-funk brevity with two remarkable epics: the title track, which winks at his haters, and “Do Me, Baby,” a slow jam with an orgasmic scream so good it sounds like Prince is trying to impregnate you with just his vocals. Prince’s first two albums revealed how absurdly talented he was, and Dirty Mind revealed how freaky he was, but Controversy was the first album that hinted at the vastness of his ambitions. —Zach Schonfeld

The album was called Controversy and 23-year-old Prince was ready to cause a lot of it, from the Lord’s Prayer he coyly recites in the middle of the title track to the Reagan-baiting “Ronnie, Talk to Russia” and gleefully perverted “Jack U Off.” If on Dirty Mind sex was a compulsion, on Controversy it’s a full-blown ideology, one that revels in promises of sexual revolution and euphoric battle chants (“People call me rude / I wish we all were nude,” etc). The Purple One continued to write, produce, and perform nearly every instrument himself, expanding the parameters of Dirty Mind’s synth-funk brevity with two remarkable epics: the title track, which winks at his haters, and “Do Me, Baby,” a slow jam with an orgasmic scream so good it sounds like Prince is trying to impregnate you with just his vocals. Prince’s first two albums revealed how absurdly talented he was, and Dirty Mind revealed how freaky he was, but Controversy was the first album that hinted at the vastness of his ambitions. —Zach Schonfeld

4. Elvis Costello: Trust It wasn’t quite a massive success like This Year’s Model or My Aim is True, but Trust is Elvis Costello at his most biting and cynical, rattling off social commentary like “the teacher never told you anything but white lies” on “New Lace Sleeves” and demonstrating his trademarked wit with lines like “the long arm of the law slides up the outskirts of town” on “Clubland.” Sonically, it’s all over the place in a good way, as Costello makes his first real attempts to hop from genre to genre, something that would come to be expected from him later in his career. —Bonnie Stiernberg

It wasn’t quite a massive success like This Year’s Model or My Aim is True, but Trust is Elvis Costello at his most biting and cynical, rattling off social commentary like “the teacher never told you anything but white lies” on “New Lace Sleeves” and demonstrating his trademarked wit with lines like “the long arm of the law slides up the outskirts of town” on “Clubland.” Sonically, it’s all over the place in a good way, as Costello makes his first real attempts to hop from genre to genre, something that would come to be expected from him later in his career. —Bonnie Stiernberg

3. Brian Eno and David Byrne: My Life in the Bush of Ghosts When I need a quick shot of adrenaline to get work done, I often turn to Brian Eno and David Byrne’s still-mystifying avant-funk masterpiece, My Life in the Bush of Ghosts. The African-inspired grooves are both paranoid and energizing, and the sampled voices—borrowed from such unusual sources as a real exorcism, a Qur’anic recital, and a slick-talking preacher’s broadcast sermon—are more mysterious and less distracting than singalong pop vocals; they function as conveyors of sound more than meaning. The album was released around the same time early hip-hop pioneers were experimenting with sampling, but sounds as if it emerged from another planet: It pioneered the use of samples as lead vocals 20 years ahead of The Avalanches. Its radical techniques proved influential on artists as wide-ranging as Kate Bush, Pink Floyd and Burial, and even presaged the later legal questions regarding sampling—the album’s release was reportedly delayed by the difficulty of obtaining sample clearances. —Zach Schonfeld

When I need a quick shot of adrenaline to get work done, I often turn to Brian Eno and David Byrne’s still-mystifying avant-funk masterpiece, My Life in the Bush of Ghosts. The African-inspired grooves are both paranoid and energizing, and the sampled voices—borrowed from such unusual sources as a real exorcism, a Qur’anic recital, and a slick-talking preacher’s broadcast sermon—are more mysterious and less distracting than singalong pop vocals; they function as conveyors of sound more than meaning. The album was released around the same time early hip-hop pioneers were experimenting with sampling, but sounds as if it emerged from another planet: It pioneered the use of samples as lead vocals 20 years ahead of The Avalanches. Its radical techniques proved influential on artists as wide-ranging as Kate Bush, Pink Floyd and Burial, and even presaged the later legal questions regarding sampling—the album’s release was reportedly delayed by the difficulty of obtaining sample clearances. —Zach Schonfeld

2. Kraftwerk: Computer World Germany’s Kraftwerk—despite portraying themselves as cold, clinical, precise machinery—was also vague and indeterminable enough to be everything to everybody. Afrika Bambataa and hip-hop claimed them as their own, as did Iggy Pop and David Bowie. Same goes for the dance floors of house and techno, not to mention the New Romantics and anyone who’s deployed drum machines and synths in the last 40 years to mimic human sentiment. For all of their portrayal as robotic entities, Kraftwerk’s 1981 album Computer World studied the increasingly blurry lines between humanity and technology, carefully wrapping trenchant observations in their winsome, electrified lullabies that merge classical structures to electro-pop succinctness. —Andy Beta

Germany’s Kraftwerk—despite portraying themselves as cold, clinical, precise machinery—was also vague and indeterminable enough to be everything to everybody. Afrika Bambataa and hip-hop claimed them as their own, as did Iggy Pop and David Bowie. Same goes for the dance floors of house and techno, not to mention the New Romantics and anyone who’s deployed drum machines and synths in the last 40 years to mimic human sentiment. For all of their portrayal as robotic entities, Kraftwerk’s 1981 album Computer World studied the increasingly blurry lines between humanity and technology, carefully wrapping trenchant observations in their winsome, electrified lullabies that merge classical structures to electro-pop succinctness. —Andy Beta

1. Rush: Moving Pictures Rush drummer Neil Peart once said that if it were up to him, he would have skipped the band’s growing pains in the 1970s and made Moving Pictures their first album. Well, sure: Moving Pictures, Rush’s eighth studio album, remains their biggest release 40 years later, and also one of their best. Peart, singer/bassist Geddy Lee and guitarist Alex Lifeson spent the ’70s refining how they made music, paring back the sprawling multi-part song cycles in favor of tighter structures that increasingly incorporated synthesizers, and replacing the sci-fi and fantasy themes with lyrics celebrating dreamers and misfits. It all coalesced in opening track “Tom Sawyer,” from the distinctive whirring synth line that ignites the song at the start to muscular guitar leads from Lifeson and powerhouse fills from Peart that have fueled generations of air-drummers. Though Side 1 has the best-known songs, which also include “Limelight” and the trio’s headlong display of musical chops on the instrumental “YYZ,” Side 2 is plenty strong, too. “The Camera Eye,” Rush’s last song to stretch past 10 minutes, is almost meditative, while the spiky reggae vibe on album closer “Vital Signs” demonstrated that, despite the band’s enduring reputation for proggy nerd-rock, Rush was continuing to incorporate new and different influences. —Eric R. Danton

Rush drummer Neil Peart once said that if it were up to him, he would have skipped the band’s growing pains in the 1970s and made Moving Pictures their first album. Well, sure: Moving Pictures, Rush’s eighth studio album, remains their biggest release 40 years later, and also one of their best. Peart, singer/bassist Geddy Lee and guitarist Alex Lifeson spent the ’70s refining how they made music, paring back the sprawling multi-part song cycles in favor of tighter structures that increasingly incorporated synthesizers, and replacing the sci-fi and fantasy themes with lyrics celebrating dreamers and misfits. It all coalesced in opening track “Tom Sawyer,” from the distinctive whirring synth line that ignites the song at the start to muscular guitar leads from Lifeson and powerhouse fills from Peart that have fueled generations of air-drummers. Though Side 1 has the best-known songs, which also include “Limelight” and the trio’s headlong display of musical chops on the instrumental “YYZ,” Side 2 is plenty strong, too. “The Camera Eye,” Rush’s last song to stretch past 10 minutes, is almost meditative, while the spiky reggae vibe on album closer “Vital Signs” demonstrated that, despite the band’s enduring reputation for proggy nerd-rock, Rush was continuing to incorporate new and different influences. —Eric R. Danton