Bob Dylan and the Rolling Stones aren’t the only musicians to dream of another way to perform for audiences. Why couldn’t their shows be less grandiose and distancing, more intimate and spontaneous, with props, costumes and many different acts—like the small traveling circuses of pre-Beatles Europe preserved in the films of Federico Fellini, Ingmar Bergman and Marcel Carne?

Unlike most such dreamers, Dylan and the Stones actually put their ideas into practice and then documented the results with movie cameras and tape machines. This summer that documentation has been released in fuller form than ever before. Dylan’s 1975-76 Rolling Thunder Revue is the subject of both a new Netflix documentary directed by Martin Scorsese and a mostly new 14-CD box set. And the 1968 Rolling Stones Rock and Roll Circus is the subject of an expanded and remastered box set with a DVD, Blu-Ray disc and two audio discs.

What this avalanche of film footage and music recordings reveals is not only scattered moments of inspired brilliance but also long stretches of sheer folly and self-indulgence. Together they demonstrate that it’s possible to create more personal, less predictable performance situations. At the same time, that very lack of predictability—or discipline, you might say—can lead to embarrassing moments as well as exhilarating ones and can make it very difficult to pay the bills. The high points are high enough to keep alive the dream of the rock ’n’ roll show as a kind of carnival, but the low points make clear the challenges of mounting such a show.

Mick Jagger conceived the Rock and Roll Circus as a promotional film for the Rolling Stones’ latest album Beggar’s Banquet, released December 6, 1968. Two days later, filmmaker Michael Lindsay-Hogg (who would two years later direct the Beatles documentary Let It Be) took his cameras inside a circus tent erected on a London soundstage.

To make it more of an event, Jagger invited Jethro Tull, the Who, Marianne Faithfull, Taj Mahal, Eric Clapton and John Lennon to join the festivities. Clowns, fire-eaters and trapeze artists performed between the musical sets, and the few hundred people in the audience were given felt hats and orange or yellow ponchos to wear. Jagger was dressed as a circus ringmaster, Keith Richards as an eyepatch pirate, and Bill Wyman as a red-nosed clown.

This all sounds charming, but it wears thin quickly. It might be fun for the celebrities who dress up like characters in a Fellini movie, but they’re not actors and their nervousness translates into arch, campy line readings that quickly grow tiresome. The hired circus performers were good but not great, so the evening was nothing special as a circus. It all came down to the musical sets.

And they are undercut by the recognition that Faithfull, Jethro Tull’s Ian Anderson and Jagger on the encore are all singing to pre-recorded tracks. It’s American Bandstand at the big top. Moreover, the evening’s special attraction, the Dirty Mac band, featuring Lennon, Clapton, Richards, Yoko Ono, violinist Ivry Gitlis and the Hendrix Experience’s Mitch Mitchell, turned out to be an under-rehearsed, pick-up blues band with a screeching female vocalist. Which, to be fair, is exactly what it was.

By contrast, Taj Mahal’s quartet, featuring the great guitarist Jesse Ed Davis, demonstrated just how powerful a well rehearsed, crackerjack blues band could sound. They delivered the Memphis classic, “Ain’t That a Lot of Love,” in the finished film plus three more songs found on the bonus disc of unreleased tracks. And the Who’s condensed, seven-minute version of its first and best rock-opera medley, “A Quick One While He’s Away,” was a delight. The four musicians were loose and witty, seemingly liberated by the intimacy of a circus tent.

The Rolling Stones refused to release this ambitious effort for 28 years, supposedly because they were unhappy with their own set. The set did have its problems. The show had begun at 2 p.m. on December 11, but the Stones—who’d been busy introducing acts and trying to keep the chaotic project going through countless delays—were exhausted by the time they finally started playing at 5 a.m. the next morning. And Brian Jones, playing his final public show with the band before the band fired him seven months later, was more or less a zombie.

The opening song, “Jumping Jack Flash,” was more “Limping Jack Crash.” But things improved as they moved into the songs from the newly released Beggar’s Banquet. ”Parachute Woman,” “No Expectations” and “Sympathy for the Devil” all sounded strong with Richards playing spirited lead and rhythm guitar to make up for Jones’ lack of contribution and Jagger singing to the front row of the circus rather than the upper deck of an arena.

If The Rolling Stones Rock and Roll Circus was a one-off event that was kept under wraps for years, Dylan’s Rolling Thunder Revue was a very public enterprise that was on the road for two months in 1975 and another two months in 1976. In 1974, Dylan had made his first tour since 1966, once again with the Band (aka the Hawks). He released Blood on the Tracks in January of 1975 and had finished its follow-up Desire by October (to be released in January). He wanted to tour behind the two albums but not in a succession of basketball arenas as he had in 1974.

He started showing up unannounced in the tiny folk clubs of Greenwich Village, the same venues where had got his start as an unknown folkie from Minnesota in 1961-62. He reconnected with some folks from those years—Joan Baez, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, Eric Anderson and Phil Ochs—and some newer faces such as Patti Smith. Dylan liked the feel of it, the notion that many different singers were playing for each other as much as the close-by audience. There was a loose, give-and-take spontaneity to it. It was like an old-fashioned circus. Why couldn’t his next tour be that?

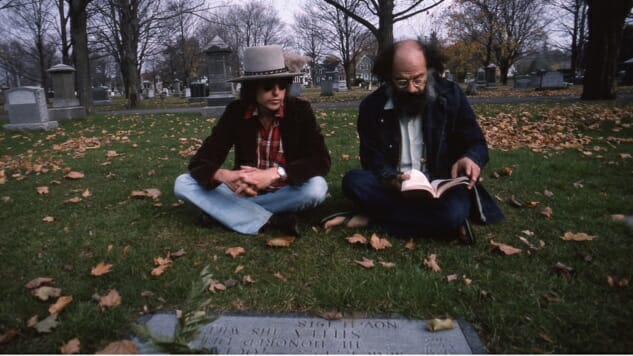

Because he was Bob Dylan, it could. He deputized Rob Stoner, the bassist on the Desire sessions, to form a core band around the musicians from those sessions. Baez, Elliott, Roger McGuinn, Allen Ginsberg, T-Bone Burnett and David Bowie’s Mick Ronson climbed on the bus; Dylan drove his own camper, and off they went to New England.

I caught up with the tour on its 10th date: November 13, 1975, at the War Memorial Coliseum, home of New Haven’s minor-league hockey team, the Nighthawks. My date was lamenting that this was a much larger hall than the tour’s previous venues. I told her, “Look where we’re sitting. If this venue was half the size, we’d be out on the sidewalk.” That’s the double-edged sword of acts playing smaller venues than normal: It’s great if you get in; it’s not so great if you don’t.

The afternoon show began with the lesser known acts. Among the highlights were a then-unknown T-Bone Burnett singing the then-unreleased “Werewolves of London” by Warren Zevon and Stoner singing “Catfish,” Dylan’s rewrite of “Maggie’s Farm,” this time about the Oakland As’ pitcher Catfish Hunter. Someone shouted “We want Dylan!” Someone else shouted, “We want Ted Mack,” the host of radio and TV’s Original Amateur Hour.

“This is a song I wrote for a girlfriend in a bar once,” announced Dylan’s longtime pal Bobby Neuwirth. “I’m playing her guitar tonight, but she couldn’t be with us tonight.” He sang “Mercedes Benz, the evening’s first high point. “That’s for Janis,” Neuwirth said afterward. “She would have enjoyed this party. When I see her in Hell, I’m going to kick her where it hurts.”

Ramblin’ Jack Elliott was next, shuffling onstage with his weather-beaten face under a big white cowboy hat. Strumming some chords, he remarked, “This is the first song I ever heard Woody sing. He was traveling the railroads with his fiddle case. The police pulled him off the train because there was an outlaw riding the trains at the same time with a gun in a violin case. His name was Pretty Boy Floyd.”

Elliott sang Woody Guthrie’s “Pretty Boy Floyd,” and thus provided a link between the evening’s festivities and a long line of troubadours that go back through Guthrie and Jimmie Rodgers. He was a living reminder that Dylan and his generation didn’t invent this music. Roger McGuinn came out and played banjo as Elliott sang Tim Hardin’s “If I Were a Carpenter.”

“We got another friend for you now,” Neuwirth announced, and the band cranked up the chords for “When I Paint My Masterpiece.” Out of the shadows emerged Dylan, wearing a black vest and a white cowboy hat, its flat brim loaded with red and orange flowers. He added a new line to the song, “It sure has been one hell of a life.” Dylan was only 34 this night, but he had already earned the right to defy his own advice and “look back.”

He over-sang the opening number, but he managed to rein in his voice for impressive versions of “It Ain’t Me, Babe,” “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll” and “Romance in Durango.” The first of the trio was dedicated to Leonardo da Vinci and the last to Sam Peckinpah as the associations began to widen beyond Guthrie and Baez to a broader artistic community. Dylan put down the guitar for “Isis” and unfortunately reverted to overstatement, spitting out each line melodramatically, as if the theatrical nature of the show had brought out his inner hamminess.

After intermission, the lights went down on the audience and up on the curtain, painted like a circus poster with strongmen and acrobats in different corners. Behind the curtain, one could hear an acoustic guitar and two voices. By the third line, the crowd realized it was Dylan and Baez singing “The Times They Are A-Changin’.” The audience was on its feet by the time the curtain finally lifted, revealing their legs, then their arms, then their faces singing into a single microphone.

That was followed by duet versions of Merle Travis’s 1946 country classic “Dark as a Dungeon” and Johnny Ace’s 1954 R&B hit “Never Let Me Go.” They’re not what some people would consider folk songs, but they worked splendidly in that role, proving that the American music has more roots than the obvious ones. Each singer supplied what the other lacked—Baez provided the purity of sound and Dylan the dramatic tension. They did the same on Dylan’s “I Dreamed I Saw St. Augustine.”

“This one is dedicated to Richard Manuel,” Dylan said next. “We wish he was here, but he couldn’t come.” It was “I Shall Be Released,” and Baez delivered the thrilling high notes of Manuel’s vocal with the Band, while Dylan added the growling urgency. They had once been lovers and musical partners; she had helped make him famous by showcasing him on her tours. He had declined to return the favor on his 1965 acoustic tour of England. The moment they broke up in a British hotel room is captured in the film Don’t Look Back. Now, a decade later, they were back at the same mic.

Dylan exited at that point, leaving Baez to do her own mini-set, beginning with “Diamonds & Rust,” her own bittersweet composition about her relationship with Dylan. She also sang an a cappella gospel song, a recent country hit, Guthrie’s “Pastures of Plenty,” the Band’s “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” and “Long Black Veil,” the 1959 Lefty Frizzell country hit also recorded by the Band, who seemed to hover over the evening even in their absence. McGuinn led the house band through “Chestnut Mare” and “Eight Miles High.” The latter song included not only the evening’s best guitar solo but also some unexpected go-go dancing by Baez.

The stage went dark, and then a spotlight came up on Dylan alone on a barstool, his acoustic guitar on his left knee, performing “Tangled Up in Blue” with his best vocal of the night, carefully controlled but with a knife’s edge. The band returned and Dylan ran through several songs from the soon-to-be-released Desire: “Oh, Sister,” “Hurricane,” “One More Cup of Coffee” and “Sara.” Stoner, violinist Scarlet Rivera, drummer Howie Wyeth, percussionist Luther Rix and singers Blakely and Steven Soles all recreated their parts from the recent studio sessions.

Desire has never gotten its critical due, perhaps because critics had used up all their variations on the “Dylan is back” theme with the preceding album, Blood on the Tracks. But Desire contained one of his best protest songs (“Hurricane”), his best divorce song (“Sara”), one of his most moving love songs (“Oh, Sister”), his bravest attempts at third-world music (“Mozambique” and “Black Diamond Bay”) and some of Emmylou Harris’s best-ever harmony singing. The album also includes the worst protest song of Dylan’s career, “Joey,” a turgid, misguided ode to the gangster Joey Gallo. Nonetheless, it’s a brilliant collection of songs, and it would be nice if the renewed attention to the Rolling Thunder Revue rebounded onto Desire.

The New Haven show wound up with a full band version of “Just Like a Woman,” Dylan and McGuinn trading verses—and making up new ones—on “Knocking on Heaven’s Door,” and the full cast plus Ginsberg singing along to Dylan and Baez on the third Guthrie song of the evening, “This Land Is Your Land.”

As this song-by-song description demonstrates, the Rolling Thunder Revue is very different from the way it is presented in the Columbia box set and the Scorsese film, which limit themselves to the songs Dylan sang alone or with others. They thus ignore the variety-show aspect of the project, the crucial notion that many different singers would contribute to each show, that music-making works best when a whole community contributes and not just a lone genius. That was the idea for the Rolling Stones’ Rock and Roll Circus as well.

The live performances, though, were only one aspect of the Rolling Thunder Revue. Dylan also wanted to make a movie while traveling through New England. He hired his Eat the Document collaborator Howard Alk as cinematographer and playwright Sam Shepard as screenwriter and cast the Revue’s performers in fictional roles. The central romantic triangle involved Renaldo (Dylan), Clara (his wife Sara) and the Woman in White (Baez). Dylan jettisoned Shepard’s script and encouraged the cast to improvise scenes based on his cryptic instructions.

The result, Renaldo and Clara, was meant to be a beguiling mix of fiction and rock’n’roll documentary, but the four-hour original version (which I sat through in a New York theater in 1978) proved insufferably incoherent. It merely goes to prove that being a talented songwriter does not make you a talented filmmaker—a lesson Paul McCartney leaned the hard way in writing and directing 1968’s Magical Mystery Tour, which featured the Beatles joining an assortment of locals on a vacation bus tour from Liverpool to the seaside resort of Blackpool.

That project, which resulted in a soundtrack album plus the movie, is a kind of cousin to the Rolling Stones’ Rock and Roll Circus and Dylan’s Rolling Thunder Revue. All three try to evoke the atmosphere of a small traveling circus with all of its music, comedy and theatrical weirdness—with both spine-tingling peaks and face-planting flops.

Renaldo and Clara might have been a fiasco, but the footage was eventually reshaped into a movie that fulfilled the original promise of fiction and non-fiction combined in an intoxicating mixture. That movie, Martin Scorsese’s Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story has just been released this summer as a Netflix Original. To the 1975 shots, Scorsese has added new interviews with characters both real and imagined.

The director tips his hand in the opening scenes with a clip from a Georges Melies short about a magician making a woman disappear with the help of the camera; Scorsese will be playing similar tricks. He invents three characters—filmmaker Stefan van Dorp, concert promoter Jim Gianopulos and U.S. congressman Jack Tanner—who never existed in real life. Scorsese not only interviews all three about their experiences with the Rolling Thunder Revue but also interviews Dylan about his interactions with the three.

It’s all very witty, and gives the documentary a whiff of fantasia that was the aim of the original tour and the original movie. In addition, Scorsese deftly weaves together the on-stage performances, the interviews and the backstage rehearsals and conversations into a 140-minute film that flows by easily. It brings the viewer along for the ride without ever bogging down.

To supplement the Scorsese film, Legacy Recordings has released a 14-CD box set, Rolling Thunder Revue: The 1975 Live Recordings. Ten of the discs are devoted to all the Dylan songs from five different shows beginning a week after the New Haven stop. Twenty-two of these tracks overlap with 2002’s cherry-picked, two-CD set, The Bootleg Series Vol. 5: Bob Dylan Live 1975, The Rolling Thunder Revue, but the complete shows provide more songs and an idea of how the music flowed each night.

But the real treats in the new box set are the three discs of rehearsals and the bonus disc of rarely performed songs from the tour. Dylan had a tendency, especially once he started wearing white face paint, to overstate everything on stage, as if he were singing without a microphone. But in the rehearsals, he was relaxed and singing just to the people around him—and often turned in his best vocals there.

Best of all are the surprising covers: a world-weary version of Curtis Mayfield’s “People Get Ready,” a timeless version of the Dubliners’ “Easy and Slow,” a campfire version of Smokey Robinson’s “Tracks of My Tears,” a melancholy reading of the old cowboy song “Spanish Is the Loving Tongue” and a heartfelt version of Peter LaFarge’s “The Ballad of Ira Hayes” at the Tuscarora Indian Reservation.

So how can we assess these efforts to reimagine the rock ’n’ roll tour? We can judge them four ways: as special event, as recorded music, as documentary film and as financial venture. As special event, both the Rock and Roll Circus and the Rolling Thunder Revue worked. From the make-up and costumes to the circus trimmings, from the surprise guests to the pop-up nature of the gigs, these were shows unlike any other.

As recorded music, they fared less well. The same atmosphere that made the shows so unusual also encouraged the performers to overexert and overemote, creating overblown performances that were less emotionally compelling than the more restrained studio versions. With the release of the Scorsese doc, there’s been a lot of critical chatter that Dylan’s performances on the Rolling Thunder Revue far outdid the 1974 arena tour with the Band. But if you compare the audio side-by-side, especially if you listen to the bootlegs of the early stops on the ’74 run, the shows with the Band are superior. The backing musicians were much better and so was the singer (Dylan in restrained mode vs. Dylan in unrestrained mode). Rolling Thunder was a better event, but the Band tour was better music.

Lindsay-Hogg’s Rock and Roll Circus and Dylan’s Renaldo and Clara (and Magical Mystery Tour too) are all done in by their pretentious archness. Hard Rain, the 1976 NBC-TV special filmed at the tail end of the Rolling Thunder’s second leg, was as dispiriting as the exhausted venture had become. Scorsese’s new film, by contrast, is an utter delight.

But as financial venture, these were all fiascos. You can’t bring together a bunch of stars and put them into small venues for very long without running up lots of debt. The Rock and Roll Circus was meant to be a promotional film, but the costs became even more indefensible when the film went unreleased for years. Rolling Thunder was losing so much money on its early dates that it started playing larger venues after Thanksgiving and even more so on the 1976 second leg through the South and Southwest. That’s why you’re unlikely to see anything like it ever again.