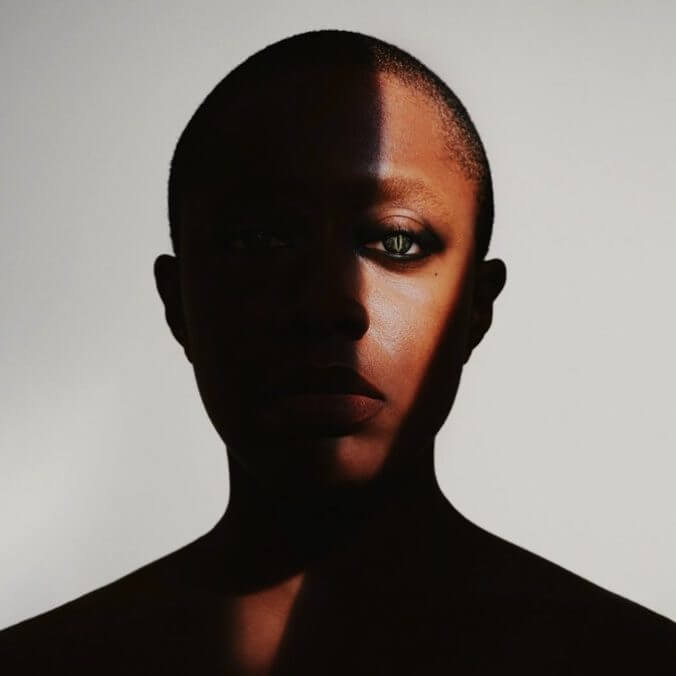

The Many Voices of Cécile McLorin Salvant

Photos by Karolis Kaminskas, courtesy of Nonesuch Records

The best singers can fashion a different voice for each song—adjusting attack, attitude and texture to inhabit a tune from start to finish. Cécile McLorin Salvant goes beyond that; she often creates a different voice for each section of a song. It’s a radical approach that makes her the most interesting singer around today—no matter what the genre, no matter what the language.

Earlier this month at the Big Ears Festival in Knoxville, Salvant demonstrated this methodology on “Ghost Song,” the title track from last year’s album. She sang the opening verses a cappella, belting out her complaint that her lover has left her as if the song were a field holler, a protest against an unfair life in the cotton fields.

When her terrific quartet joined her for the chorus, however, she shifted gears to sing, “I’ll dance with the ghost of our love,” in a dreamy croon, as if this were a French cabaret number, and she was luxuriating in fond memories of an affair. When she repeated that same line again and again on the coda, however, her voice shifted again, becoming the crazed, edgy voice of a woman haunted by the song’s ghosts.

It was a remarkable tour de force, not only for her invention of the three voices but even more so for her making them seem like facets of the same song. It worked because the trio of moods were all recognizable aspects of a romantic bust-up: raw anger, lingering affection and unhinged bewilderment. Pablo Picasso was once known as a cubist for incorporating different perspectives into the same painting. Salvant is a cubist singer.

“I really love to orchestrate my voice,” she says over the phone from her Brooklyn home, “to take it through different textures, like an arrangement of a single instrument. I try to honor the story. I go through different energies when I’m talking and that comes out in my singing. It all happens very much in the moment. Yes, there are things I’ve done before, so some of it’s going to be the same. but I like to do something different in every song every night. It could be my voice, my phrasing, but nothing is fixed. That’s what’s exciting about working with these musicians.”

Ghost Song was nominated for a Grammy as Best Jazz Vocal Album, a category she’d won three times already. As far as categories go, jazz is probably the best fit for Salvant. She got her start by winning the Thelonious Monk International Jazz Competition for Vocalists in 2010, and even today her band is composed of jazz musicians. But her repertoire ranges far and wide.

Last year’s album included Kate Bush’s “Wuthering Heights,” Sting’s “Until” and the musical setting of a letter from photography Alfred Stieglitz to painter Georgia O’Keeffe. Her set at Big Ears included Tim Hardin’s ’60s folk classic “Reason To Believe,” the Appalachian murder ballad “Omie Wise” and Judy Garland’s “The Trolley Song.”

This year’s album, Mélusine, is mostly sung in French. The selections range from a 12th century troubadour song to mid-century hits by such French chansonniers as Leo Ferre and Charles Trenet as well as a tune from the 1978 French rock opera Starmania. But whatever the origins of her repertoire, Salvant applies the same cubist technique.

On the Bush song, for example, she begins without instruments, her echo-laden high soprano warbling through rapid changes of pitch as if she’s a maddened ghost on Emily Bronte’s moors. When the band comes in, however, she becomes warm-blooded and seductive. On the Sting composition, Salvant begins slowly and quietly, as if in despair that anything could repair her broken love. Once the rhythm section perks up the energy, though, she sings confidently as if reconciliation is imminent. In the end, however, she lapses back into melancholy pessimism. If contradictory feelings can exist in the same person, she implies, why not in the same song?

“There’s a lot of irony in what I do,” Salvant acknowledges. “At the same time, I’m very severe and at the same time, I’m winking. I’m crying and laughing. I can’t let go of the feeling that the whole thing is absurd but it’s also tragic. When I sing Burt Bacharach’s ‘Wives and Lovers,’ I’m saying, ‘Look at this old attitude that doesn’t apply to us—but maybe it does. There’s something very real to that. I’m making fun of that, saying ‘Can you believe that we once did this?’ But I’m also saying, ‘Can you believe that it’s still happening?’”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-