David Bowie has always been a contrarian. Even during the height of his mainstream popularity in the early ‘80s, there was something vaguely sinister and uneasy about the way he endeared himself to us. Behind the designer suits and positive, ‘drug free’ messages, one could sense that constructing radio-friendly songs was just another intellectual game that Bowie was occupying himself with until the next sounds and visions came along to distract him.

The Let’s Dance era was certainly a glorious ride for Bowie and a vindication of his genius for those who had hitherto ignored his work, but it certainly wasn’t sustainable. The paradigm of icy-cool funk that “Modern Love” and “China Girl” represented couldn’t be improved upon, and for the first time in his career, David Bowie found himself in a creative corner that he had painted himself into. A decade of desperate repetition, out and out vapidity, followed by some rather desperate attempts (Outside, Earthling and Black Tie/White Noise) to regain the artistic credibility and experimental ground that he had traded away for commercial success did nothing to further his reputation or career. After a string of disappointing commercial albums such as Tonight and Never Let Me Down, it was too late to turn back; none of Bowie’s old fans were buying into his reclaimed avant-garde persona and the throngs of people who joined him with Let’s Dance had moved onto other radio-friendly artists and their pre-digested music. The unthinkable had happened: David Bowie had become irrelevant.

Things improved slightly as the new century approached. Earthling, Bowie’s drum and bass-heavy collaboration with Trent Reznor from 1997, offered a partial return to form, yet there was a palpably desperate aura around the project that suggested an artist who was desperately trying to regain his relevance. The attempt to co-opt rather than steer contemporary sounds had all of the surprise value of the disco singles that Rod Stewart and The Rolling Stones released in the ‘70s. Subsequent albums like Hours, Heathen and Reality each had some good moments, primarily because Bowie didn’t over-reach as he seemed quite content to create new material without also trying to surpass what he had done in the past. For a few years, it looked as if Bowie would be satisfied with a diminished role around the fringes of popular music, but when he suffered a heart attack after a performance during the Reality tour, he walked away, dropped off the radar and said he was finished and ready to disappear.

Until very recently, Bowie continued to maintain a low profile. When he was mentioned in the media, the stories often had more to do with rumors of poor health or with appearances at his son, Duncan Jones’ film premieres in which he was portrayed as a doting father whose own creative life was perhaps a thing of the past.

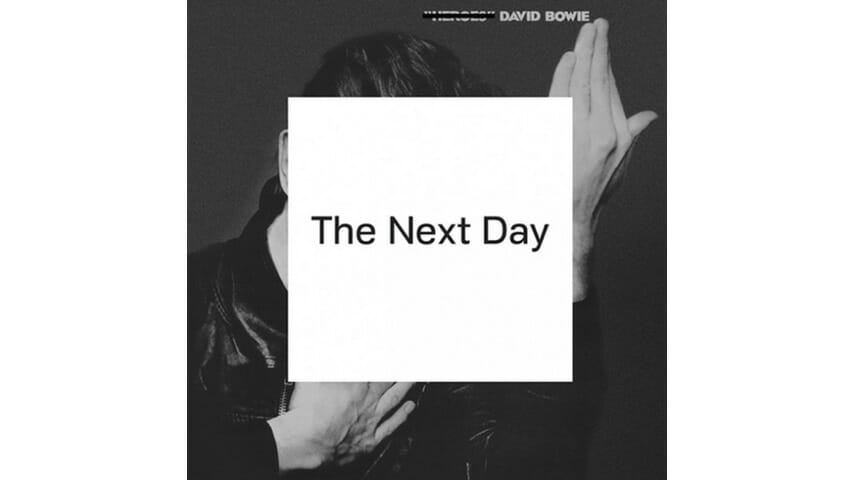

Yet, at the same time the media was speculating about the potential life-threatening diseases Bowie was contending with, the singer who grumpily told reporters that he spent his days at home watching Woody Allen movies clearly had something up his sleeve, something brewing in the lab. The fact that Bowie’s creativity was being eulogized in the press at the same time he was secretly recording a new album with Tony Visconti at the tiny Magic Shop studio in Soho, New York has already become a familiar story. Some have said that all of this recent hubbub is nothing more than a manifestion of the newest incarnation of Bowie’s continually expanding persona: Bowie as trickster, manipulator of social media and castigator of celebrity culture. While that perspective may not be entirely accurate and might be a product of wishful thinking, it’s certainly undeniable that with Bowie, it’s never been simply about the music. He’s always been about a full-spectrum presentation that includes clothes, makeup, film and visuals to offer a complete package. In that light, the Bowie that emerges on The Next Day is “archetypal artist as retired veteran” who can’t keep his opinions to himself anymore. As much as he’s tried to be the retiree “with a nice life” as he sings on “The Stars (Are Out Tonight),” the banal stupidity and vapidity of modern life that he was probably much too busy to engage with during his prime seems to have driven him around the bend to a point of absolute distraction. The sexless celebrities, formulaic music and lack of vision and risk appear to have pissed him off to such an extent that he couldn’t hold his tongue or stay away from the recording studio. All of this is great news, for Bowie has always been at his best when he’s outraged, sneering and making sure his listeners know in no uncertain terms that most of what happens around him is beneath his contempt.

David Bowie is sneaky. When he leaked “Where Are We Now?,” the delicate, lyrically dense ballad a month before the release of The Next Day, he couldn’t resist playing the trickster again, allowing people to anticipate that his new music would offer a continuation of the rather simple song structures he explored in Heathen and Reality. In truth, none of the other songs on The Next Day sound remotely like “Where Are We Now?” With its sneering guitars, booming percussion and fingers-on-the-blackboard synthesizer riffs, the music on the new album finally defers to the kind of crunching industrial soundtrack with a bad attitude that Bowie’s disaffected fans have waited for since Scary Monsters—his last truly great album—came out in 1980.

The Next Day is not the kind of listener-friendly, career-encompassing record that many of Bowie’s contemporaries have often settled for of late. Unlike many older artists, who want nothing more than to recapture the sounds of their heydays, Bowie sounds genuinely engaged in these new songs, as if he has rediscovered the joy and satisfaction of writing and performing challenging music. As much as one can hear echoes of his former work in the grooves of the new material—the sonic ghosts of Ziggy Stardust, Heroes and Lodger haunt the corners of many of these songs—Bowie has clashed with and extended every one of his old ideas into new territory to create songs that are real, timely and pertinent. Not an easy task for somebody who has been creating for nearly half a century.

For the first time in a long time—exactly how long is a matter of debate—one can say with complete honesty that every song on the newest Bowie album is worthy of a concentrated listen and a deeper look. Not one of the 14 new tracks could be considered chaff or filler, which may be a reflection of the extra time and lack of any imposed deadline to work towards.

The Next Day is a record that isn’t afraid to be nasty, and for many people it will be refreshing to hear Bowie eschew politeness and good behavior to some of the most engaging lyrics he’s sung in decades. Perhaps the best of these new songs with a bad attitude is “The Stars (Are Out Tonight)” in which he bemoans the “sexless and unaroused characters” that pass for celebrities these days. He clearly wants us to know that decadence and depravity aren’t what they used to be, and that it’s a shame.

The sense of fatalism and the inevitability of doom that permeated many of Bowie’s best songs from his heyday has come back in full force with The Next Day. On tracks like “Dirty Boys,” when Bowie sings “the sun goes down and the die is cast” over seriously crunching guitars and squawking horns, one really gets the sense that he believes the end is near. The sense of alienation is profound; as much as Bowie’s never been a warm and cuddly artist in the Paul McCartney sense, he’s viewing everything from a new distance on these songs. He’s become an elder outsider who reports everything from a perspective that is almost unspeakably remote. His patience with the “new world” and the young who celebrate it is paper-thin, so when he sings “it’s the darkest hour…your country’s new, your friends are new, your house and even your eyes are new, your maid is new, and your accent too, but your fear is as old as the world it fills” on “Love is Lost” you have to wonder if there’s a glimmer of hope anywhere in Bowie’s universe. If there is, it’s hard to hear it in the off-kilter synthesized Arabic trills or metallic guitars that conjure up a sense of violence that goes all the way back to Diamond Dogs.

The Next Day isn’t an album that can be digested overnight. There’s too much going on in each of these 14 songs to take in all at once. The title track sounds vaguely like a lot of the songs on Lodger and Heroes, but there’s nothing wrong with that; they sound more like the resumption of an unfinished conversation than a tired retreading of ideas that were new decades ago. All in all, the sonic universe the album creates couldn’t be more appealing. Whether it’s the percussive resumption of the intro to “Five Years” that propels “Dancing Out In Space” or the cracked beauty of “I’d Rather Be High” and ”(You Will) Set The World On Fire,” The Next Day offers an embarrassment of riches that should keep listeners busy for weeks and months to come. Honestly, when was the last time you could say that about a new record?

What David Bowie will do in response to the positive response this latest career resurrection is receiving is anyone’s guess. He’s quite understandably indicated that he’s reluctant to tour and interact fully with the starmaker machinery again, so it’s unlikely that the man who was once the Thin White Duke will be showing up in your town anytime soon. But, whether The Next Day is a worthy parting shot from Bowie, the artist, or merely an opening volley that signifies the beginning of a new phase remains to be seen.