How Elton John Paved His Very Own Yellow Brick Road Through the 1970s

John's three-year retirement plan is fitting: On the basis of his prolonged 1970s run alone, he's a rock immortal.

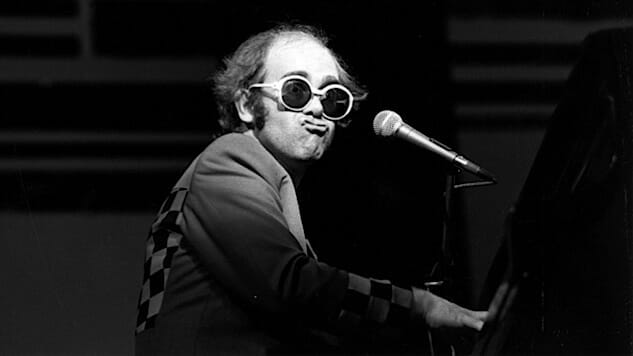

Photo: Getty Images

When Elton John announced late last week that his retirement from touring would arrive three years and exactly 300 concerts from now, he set in motion one of rock’s longest-ever goodbyes. It’s fitting: John’s career has been so epic and his popularity so enduring that he’ll never really leave us. On the basis of his 1970s run alone, he’s a rock immortal.

The string of platinum albums started in October of 1970 with his third album, Tumbleweed Connection, followed by Madman Across the Water, Honky Chateau, Don’t Shoot Me I’m Only the Piano Player, Goodbye Yellow Brick Road, Caribou, Captain Fantastic and the Brown Dirt Cowboy and Rock of the Westies. Not only did the albums sell, they were (mostly) great, and he was recognized almost immediately as a post-Beatles pop-music game changer. But John also dominated the pop charts in a Beatlesesque way: top 10 singles in the period after 1970’s “Your Song” include “Rocket Man,” “Honky Cat,” “Crocodile Rock,” “Daniel,” “Goodbye Yellow Brick Road,” “Bennie and the Jets,” “Don’t Let the Sun Go Down on Me,” “The Bitch Is Back,” “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds,” “Philadelphia Freedom,” “Someone Saved My Life Tonight” and “Island Girl.”

You couldn’t listen to pop radio for an hour from anytime between 1970 and 1975 without hearing a current Elton John hit. Here’s John with his longtime band (Davey Johnstone on guitar, Dee Murray on bass and vocals, and Nigel Olsson on drums and vocals) performing “Rocket Man” at Saratoga Performing Arts Center in 1982:

And listen here to John in Central Park in 1980, playing perhaps his most personal and acclaimed hit, “Someone Saved My Life Tonight,” where his songwriting partner, lyricist Bernie Taupin, channeled John’s psychological strife at the height of his fame.

Ironically, John’s popularity has diminished his reputation among some classic-rock aficionados. How could anything so beloved by radio stations spanning age groups, genders and races really be that special? The Jeff Bebe character in “Almost Famous” says it best (in the director’s cut): “Show me any guy who ever said he didn’t want to be popular, and I’ll show you a scared guy. I’ve studied the entire history of music. Most of the time, the best stuff is the popular stuff. It’s much safer to say popularity sucks, because that allows you to forgive yourself if you suck.”

For John, the hits came at a price—not just the usual drug and alcohol abuse but bulimia and suicidal depression, all compounded by being center stage in one of the biggest, longest-running circuses in rock history. Unlike the Beatles, John couldn’t periodically leave it to another songwriter to carry the band. Author Dean Keith Simonton talks about this in Greatness: Who Makes History and Why. Despite Taupin writing the lyrics, John was responsible for creative success or failure, measured by sales. He was charged with churning out hit after hit, which explains in part why he released 12 studio albums in the 1970s. Compare that with a band, which Simonton notes is more like contestants in a tug of war: At any point, “any one member can feel free to relax without the embarrassment of disclosure.”

But John was in a zone like few have ever experienced. And he knew it. As he told the BBC, “I would write at breakfast at the table. The band would join in. And by the time breakfast was over, we’d written and rehearsed two songs.” John sings about this time in the autobiographical title track from 1975’s Captain Fantastic and the Brown Dirt Cowboy: