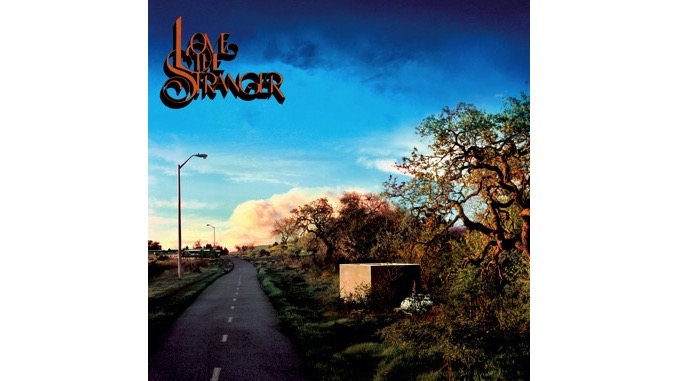

Friendship Finds a Peace of Sorts on Love the Stranger

When Friendship released “Hank,” the second single off their new album, it came with a music video directed by none other than Joe Pera. The video is a characteristically Pera-esque slice of life, following a painter and a woodworker through the rocky shores and spruce-speckled woods of Cranberry Island, where frontman Dan Wriggins once worked as a lobster fisherman just off the coast of his native Maine. Over the footage, Wriggins’ voice paints symbolic sketches of fraying tools and a life that’s trying to hold itself together one day at a time.

That the pairing fits so seamlessly speaks to the affinity of Friendship and Pera’s work. Their art doesn’t seek to escape the everyday, but places it under a microscope instead, exposing it for all its tiring minutiae and subtle beauty, lingering on the ways we carve out pockets of joy within the mundane.

Love the Stranger, Friendship’s first release with Merge Records, hits like a call out of the blue from an old friend, touching on the passage of time, its disappointments and humble victories, and the struggle to stay kind whether or not the world returns the favor. “Still swinging on my vine / Still getting up every day,” Wriggins sings in his plainspoken baritone on “St. Bonaventure,” opening the album over a loose, lap steel-inflected and snare-heavy beat. This Americana-tinged sound serves as home base for the album, but it doesn’t keep the band from branching out.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-