Ashley Frangipane, better known as Halsey, has made it a point to defy labels in her rise to pop’s upper echelons. It’s a tricky thing to negotiate that genre fluidity with the pop machine’s penchant for framework—and, at times, it feels like she’s shed and rebuilt three different pop star personas since emerging on the national stage with her 2015 debut, Badlands.

She disavowed the “tri-bi” label (bisexual, biracial, bipolar) that was thrust upon her as an upstart darling at SXSW, the mid-decade comparisons to the wave of alternative pop made by women and that certain DJ duo that may have overshadowed her solo success by climbing to number one on the Billboard charts with her. But being slippery doesn’t a superstar make, a classification that ostensibly applies to her after the past couple of years—after nabbing her first Top 10s, then her first number one single (“Without Me,” which appears here in a beguiling new light), appearing in A Star Is Born and doing double-duty on SNL.

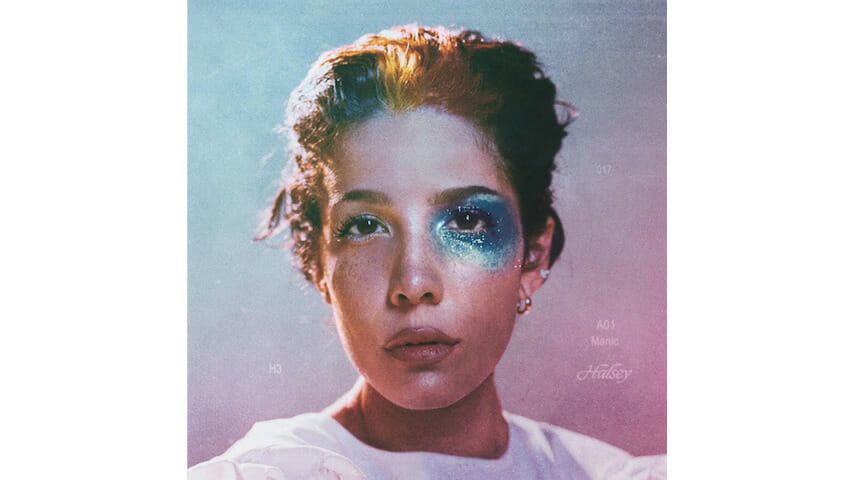

Manic is a rich and often confounding listen, an expansive album filled to the brim with the imagined worlds Halsey’s built for herself in the real one. It’s also sincerely, indefatigably Halsey: She puts her loves and ambitions on wholly earnest display, even if it doesn’t always make for the most consistent listen.

Stardom is inescapable, but Halsey’s fashioned herself a beguiling escape hatch—refracting herself through sampled movie clips, three interludes featuring three separate guests and genre exercises in country, ’90s alt-rock and twilit electropop. Throughout, she plays with autobiography, amplifying and subduing her reality by inviting other voices in the fold.

“Is it really that strange if I always wanna change?” she asks herself on “Ashley,” Manic’s opening cut. She told Rolling Stone that she wrote Manic in an extended period of mania, each song written on the basis of “whatever the fuck I felt like making.” As such, its list of collaborators is exhaustive, with studio stalwarts (Greg Kurstin, Benny Blanco, Cashmere Cat) offset with rising producers like XXXTentacion collaborator John Cunningham and Finneas O’Connell. Halsey even invites an unusual trio of artists—Dominic Fike, BTS’ Suga and Alanis Morissette in top form—for brief interludes, a display of both her eclectic taste and the inevitable genre collisions that occur throughout Manic. Morissette fares best here, a queer fantasia that filters the angst of “All The Things She Said” and pummels that song’s artificial longing into visceral, unrepentant desire.

Her truth is presented both in subtext and in blunt broadside. On “killing boys,” her good-girlfriend-goes-bad tale of revenge is made explicit by grabbing dialogue from Jennifer’s Body, then speaking her vengeance through a thumping drums and strings fight sequence. (She also makes a reference to “Uma Thurman”-ing the partner who betrayed her.)

If a lot of Manic feels like cosplay, perhaps that’s the point. Take “You should be sad,” a ramblin’ man country song replete with steel pedal. Her voice, without any twang or affect, rings in crystalline. Then she sings a damning salvo just before the song shifts into an industrial clang: “I’m so glad I never ever had a baby with you / ‘Cause you can’t love nothing unless there’s something in it for you.” Sure, both songs may be about G-Eazy, but for Halsey, it’s more compelling—and more fun—to repurpose her anguish into dressing up in her best Carrie Underwood or Megan Fox homages.

The character she most identifies with is Clementine, the anti-manic pixie dream girl played by Kate Winslet in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, devoting an entire sample (and a whole song) to her. That track, with its worn-out piano plinks and thuds courtesy of Cunningham, is a standout: Her words are unguarded and slurred, collapsing and echoing into each other. “I just need everyone, and then some,” she sings to herself.

Elsewhere, “I HATE EVERYBODY,” with its all-caps aggression, is a delicate, pretty Finneas production, with woodwinds and anthemic swells belying Halsey’s guttural sadness. It plays out like a cut from Lover, swapping Taylor Swift’s blissed-out romantics for anomie induced by desperation and loneliness.

Her costuming doesn’t always work: Halsey’s voice is overshadowed by the velocity of her nu-metal surroundings on “3am,” never quite selling the Durstian rap-rock cadence that she takes on here—unlike early single “Nightmare,” which doesn’t make the cut on Manic. Early single “Graveyard,” meanwhile, is a blank electropop mirage that feels more like a laboratory’s idea of a Halsey song—out of step with much of what else is here.

The triptych that ends Manic seems to be the comedown, the juncture where escapism is no longer enough and she’s left staring at drawers filled with baby clothes that won’t be worn due to her endometriosis-induced miscarriages and partners lost to circumstance and addiction. “929” is the most cutting thing of the bunch, showcasing a pop star reckoning with her fame and influence without the varnish and veneer that typically comes with the pop star confessional.

“I remember this girl with pink hair in Detroit,” she sing-tells over plush guitar loops. “Well, she told me, she said ‘Ashley, you gotta promise us that you won’t die.’” The kicker? Halsey thinks she lied, even though she admits she remembers her name and not half the people she slept with. It’s the sort of line that’s uncomfortably intimate, the sort of thing diehard fans are made from. It’s also the sort of thing that defines Halsey, no matter what genre she finds herself playing with next.