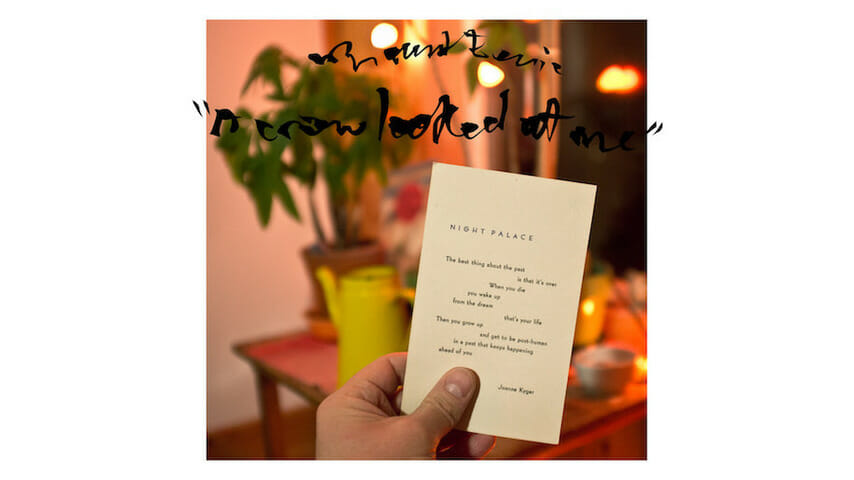

Over his prolific 20-year career Phil Elverum has written plenty of songs about mortality, probably second only to the number of songs he has written about nature. A Crow Looked at Me is the first time he has written about death, and there is no album quite like it. Following the passing of his wife, visual artist and musician Geneviève Castrée, Elverum took a couple months to grieve and then sat down in the room where she died and recorded the 11 songs that make up his eighth release as Mount Eerie. Song by song, line by line, he speaks directly to her and into her absence. The results are as engrossing as they are emotionally devastating.

Opening with a clarification that death shouldn’t be reduced to art, that the true experience of it is too profound to turn into music, he goes ahead and does just that on “Real Death.” Singing over electric guitar strums and a droning accordion, he describes the immediate aftermath of Geneviève’s dying, how rooms feel empty now, how she still gets mail. After receiving a backpack for their infant daughter that Geneviève ordered shortly before her death, he collapses on the porch in tears. “It’s dumb and I don’t want to learn anything from this,” he sings over the final strums. “I love you.”

There is no shortage of such lump-in-throat moments. Told chronologically, these songs draw the listener into the grieving process with uncomfortable specificity, often counting off the days since Geneviève died as if to prove just how little the pain fades over time. Elverum spares no details, whether describing how he’s haunted by the image of her face as she gasped for her last breaths or explaining his difficulty in throwing away her bloody tissues. On “Seaweed,” he and their daughter go to deposit Geneviève’s ashes on a hillside so she can forever watch the sunset, but it’s an empty gesture. Elverum admits that he knows her ashes aren’t her in any real sense. There are constant attempts to find some sort of meaning in this loss, and none are ever found.

Plainspoken but poetic, the album is masterful in its storytelling. On “Ravens” Elverum recalls witnessing the omen from which the album draws its name – two ravens flying toward the island where he and Geneviève had planned to build a house. Two ravens – not three – is the evidence that she’ll never be accompanying them. As multi-tracked acoustic guitar lines tumble over rumbling piano chords, he apologizes to her for giving away her clothes after she died, for looking away from her as she wasted way, and confesses that he still finds himself picking blueberries for her and cataloging the things he wants to tell her before remembering she’s dead.

That sense of clinging to someone who is already gone permeates the songwriting. The window he opened on their last morning together remains open, half because closing it would officially bring to an end their last summer together and half because he’s afraid that there’s some part of her that still needs to escape. On the hypnotic “Emptiness pt. 2,” he dreams of “self-negation,” of seeing a world with no people. But he soon acknowledges that such fantasies now seem silly. “Conceptual emptiness was cool to talk about before I knew my way around these hospitals,” he admits.

Mortality is not a character in this drama. There are no Hallmark platitudes about death teaching us to value the important things in life or reminding us to live each day with gratitude. As is typical, nature is the chosen backdrop for much of Elverum’s storytelling, but this time it offers no refuge. Comparing Geneviève’s cancer to the wildfires that licked at the outskirts of their hometown in Anacortes, Washington, on “Forest Fire,” he acknowledges that her passing does not feel natural or cleansing. The leaves fall and the house turns cold. He eventually closes the window so the room will “stop whispering.”

The album closes with perhaps its most heartwrenching tracks. On “Toothbrush/Trash” he realizes that his memories of his daily life with Geneviève are fading, that “the quiet untreasured in-between times” are being replaced by the photos he has of her. He describes the ineffable melancholy and longing that he felt throughout his early life on the darkly pulsing “Soria Moria,” capturing a sense of loneliness that he’s now resigned to living with again. The perspective shifts on the album-closing “Crow,” as Elverum addresses his daughter and ponders what it’s going to be like for her to grow up without a mother in an already troubled world. As he hikes through the woods to inspect the damage from the summer’s wildfires, his daughter dozing on his back, he notices a crow following them overhead. His daughter notices, too. “And there she was” he sings as the album ends.

More than words, what sticks with you are the images. Unlike other Mount Eerie albums, this one features very little tape hiss atmosphere or extra ambient texture, allowing you to hear every word Elverum says with clarity. But the music is not simple sonic wallpaper. The beats rise and fall, sounding eerily like a respirator. The instruments – all provided by Elverum – often enter and fade at unpredictable intervals, with tiny details buried in the mix. The melody lines are often elliptical, tied to stanzas that seem loosely tethered to meter and rhyme scheme, the number of words dictating their length. As with all of Elverum’s songs, these unfold by their own internal logic, with some abruptly changing tempo and others seeming to end in the middle of a verse. The music feels as unsettled and in-the-moment as the stories he is telling.

A Crow Looked at Me is not the most musically interesting or sonically dynamic album Elverum has ever made. There aren’t many melodies that you’ll find yourself humming as you go through your day. Most of the tracks are similarly tempo-ed and textured, and they blur together a bit, especially on early listens. They are beautifully and simply arranged, but it is not an entertaining album to listen to in any conventional sense, nor can it be shaken off easily. It is, however, the kind of album that makes all others seem frivolous while you’re hearing it. How often you want to do that will depend on how comfortable you are staring into the face of real death.