New Orleans Jazz Fest: The One of a Kind Factor

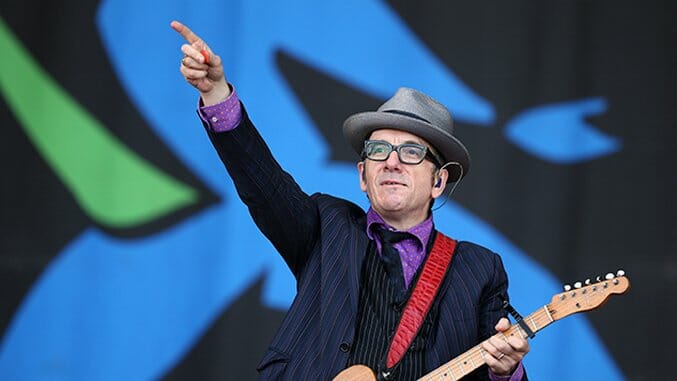

Photo by Matt Cardy/Getty Images

The rain had stopped by the time Elvis Costello & the Impostors took the stage at the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival last Thursday. The quartet’s line-up included three-fourths of the original Elvis Costello & the Attractions; the singer, drummer Pete Thomas and keyboardist Steve Nieve, who were joined by replacement bassist Davey Faragher.

The group began with a string of some of the Attractions’ best known songs: “(What’s So Funny ‘Bout) Peace, Love & Understanding,” “Watching the Detectives,” “Mystery Dance” and “Radio, Radio.” The music was so fast and furious that it almost sounded like 1979.

It was a flourish you might have heard at any stop on the band’s spring tour of America or on its coming summer tour of Europe. But what you wouldn’t hear at any of those shows was the version of “I Cried My Last Tear” that came later in the set. Bob Andrews, the legendary keyboardist for Graham Parker & the Rumour now living in New Orleans, was behind the organ for this obscure Toussaint composition.

Also joining in were the Crescent City Horns, the late Allen Toussaint’s horn section. Costello had toured in 2006 with Toussaint and the latter’s band in the wake of the album The River in Reverse. Costello had been telling stories all evening about the gifted and beloved composer who died last November, and his obvious emotion carried over into the song.

This is the other reason we go to festivals. The first reason, of course, is the chance to see a whole lot of music in a short period of time, only having to park once. That’s the Efficiency Factor. But we also go to festivals in hopes that circumstances will produce a moment that we wouldn’t encounter on a random tour stop. That’s the One-of-a-Kind Factor.

This version of “I Cried My Last Tear,” for example, would never have happened if Costello weren’t in New Orleans, where Andrews and the Toussaint horns live and where all the memories of the bandleader’s landmark collaboration with Toussaint had been recorded. This year was the 10th anniversary of Costello’s joint appearance with Toussaint at the 2006 Jazzfest, the first one after Katrina, where they unveiled their new album.

It was the most emotionally riveting Jazzfest ever, as the musicians seemed to be willing New Orleans back to life, just by the fervent hopes embodied in their performances. Perhaps it worked, for the city is not only on the rebound 10 years later but actually flourishing in many neighborhoods with new restaurants, condos under construction and renewed life in the streets.

For the anniversary, Costello resurrected four songs from The River in Reverse: “Wonder Woman,” “Ascension Day,” “Who’s Gonna Help a Brother Get Further” and the title track. The whole show echoed the high stakes and the powerful response of that 2006 festival.

It wasn’t the only tribute to Toussaint at this year’s fest. The Allen Toussaint Band hosted a long tribute that included such guest vocalists as Dr. John, Bonnie Raitt and Cyril Neville. Especially touching were Aaron Neville’s intense revival of “Hercules” and Jonathan Batiste’s spirited take on “Working in a Coal Mine.” Even a steady rain couldn’t keep the crowd from singing along on the latter.

Bob Andrews isn’t the only Brit transplanted to New Orleans; the Pogues’ Spider Stacy has been living in New Orleans since 2010. Since arriving, he’s been playing now and then with the Lost Bayou Ramblers, one of the best young South Louisiana bands around. After all, an Irish folk group and a Cajun outfit are both acoustic string bands with fiddles and accordions. Irish tin whistles and American steel guitars met inside that overlap.

A couple hours before Costello, Stacy and the Ramblers teamed up on a mini-set of Pogues’ songs, sometimes adding Cajun-French lyrics and always adding a French-Louisiana accent to such numbers as “Dirty Old Town” and “Fairytale in New York.” What didn’t change was the reckless attack the songs received.