Ah, you think darkness is your ally? You merely adopted the dark. I was born in it, molded by it.—Bane, The Dark Knight Rises

It’s true. They grow up so, terrifyingly fast. People say it every time a new baby human enters this world, but no one can ever quite prepare you for the sheer horror of watching a human—your human—grow up. It seems they literally go from watching episodes of Chowder on Netflix, to calling their Dad a nigga, overnight.

But maybe that’s just my house. I know your house. Your house is perfect. Your kids have never shocked you to within an inch of your life, seemingly defying the values you’ve worked so diligently to embed into their souls. Your kids would never jump into a gorilla enclosure at the zoo, and you would never blink your eyes for a moment in their presence so that they could. You are a magical, mythical, god-like parent, and I commend you. But this one’s for the real ones. And this one’s also for my fellow rap fans—those in and outside of the culture responsible for this great, American music.

“I was trying to compliment you.”

That’s what he said. My sweet, smart 7-year-old. Always one of the shyest kids in his class. Always changing into his pajamas as soon as he gets home from school. Loved Elephant and Piggie last year, and now it’s the My Weird School series this year, in the second grade. He has peanut allergies and demands I keep the door cracked at night. He was Leonardo this past Halloween, and Deadpool the year before. His favorite thing to do is to draw his favorite action figures and TV characters, then cut them out and play with them, like paper dolls. He’s my oldest, and, as mothers everywhere will understand, he’s my baby.

And when I asked my baby why he used this word that he’s never used before and called his Dad a nigga, he looked at both of us and explained himself so honestly, so innocently:

“I was trying to compliment you.”

Let me rewind. About 20 minutes before this, his Dad walked slowly up the stairs to the bathroom, where I was conditioning my hair. A much-needed olive oil treatment. I was massaging it in, and quite enjoying the moment because it had been so horrifyingly long. And, as mothers everywhere know, there can be no moment of bliss that isn’t followed by a moment of child-induced catastrophe. He burst in the door and said we needed to talk. Something happened with our son, and he didn’t know how to feel about it. He had never, in 7 years of our being parents, prefaced anything about our kids with a statement like this and I was terrified.

Then he told me what happened. Our firstborn son went to give him a noogie (because those are still very much a thing) and said, while pulling his father towards him, “Gimme your head, nigga.” Oddly enough, I was relieved, partly because the devastating look on his face had me fearing much worse than the use of, well, “just a word.” Okay, I’m ready for this, I thought. I’m a black woman. I write about race and politics and motherhood. I have been training for this moment. I have the answer. I know exactly what to say to my son, who has just used the word “nigga” at the tender age of seven, which—okay, in a mother’s mind—is the same age as zero. He’s still in the womb, basically. And using the word “nigga.” But it’s okay. I got this.

I had no idea what to say to him. Before coming upstairs to tell me the news, his father had managed to get him to admit that he said it because his friend says it to him at school, sometimes, especially when he’s trying to give him a noogie. And every mother knows the friend I’m talking about—the one who’s just a little too cool; the one who seems a little too mature (if you can call it that) for their age; the one who you fear will drag your perfect, sweet, never-said-nigga-before angelic, blessed child down into the depths of hell before the school year is over. He also lives about five minutes from your home, obviously.

But perhaps if it weren’t for such a child, I wouldn’t have been faced (so early on in this parenting game) with this conundrum—how do I tell my child that he shouldn’t say “nigga,” even though I listen to and love music that employs such language, and even though I understand that there’s an entire culture of people who use the word, and have adopted it and transformed it from its beginnings, as “nigger”?

In other words—the age-old question had arisen, though in a different form from that which is usually discussed—who can use the word “nigga”?

As my son’s Dad and I talked about how we would approach the issue, I found myself stressing what I saw as the real problem here: mimicry. Our son didn’t know exactly what he was saying (though he definitely knew it wasn’t appropriate, as he’d tried to avoid saying it again when his father asked him to repeat himself). He wanted to repeat something that he was hearing. And he wasn’t just mimicking his friend. I know that we live around kids and adults for whom the word is just a part of their vocabulary. And in fact, his Harlem-bred father is one of those people. Yes, there are people for whom this is actually, just another word. And although his Dad tries to censor himself more around the kids, I know—especially when he’s deep in conversation with me, or even on the phone with someone—he forgets himself and says it sometimes. Probably more than I’d like to admit.

Still, one major difference, I thought, between my son and his Dad is that my son is not of the culture, not in that way. My son is being raised by a woman who would have been slapped across the face (by a historian, activist and professor), had that word left my lips. Sure, my mother knew the kind of music I loved, and got me those tickets to my first concert, the Hard Knock Life Tour, but she also couldn’t wrap her brain around the fact that my beloved DMX had a song called “My Niggas” (which she only knew because she read about it in a review for the concert—she’d certainly never heard the lyrics coming out of my mouth, though I rapped every word of them and every other great song of his, when she was out of earshot). Thus, “nigga” was a word she allowed me to ingest through music, as long as I understood that, because of its history—because of what she believed it would always signify—I could never use the word.

But that’s only one-half of the cultural legacy that gets passed on to my children. My son is also being raised by a father who has been hearing the word since infancy. While I mostly encountered it in the music I loved, and around some of my friends who used it, my son’s Dad is someone who was, basically, always “allowed” to use the word. His grandparents, I’m sure, used the word more than I ever have. Unlike me, unlike my mother—these are people who are of the culture. People like me can attempt to adopt that culture and the language that comes with it, but —even though I’m black and I grew up listening to rap—I can’t make the same claim as my son’s father—to have been born into it, and molded by it.

So as I talked about how our son was just mimicking when he said it, I had to admit that I was, and do, too. The word “nigga,” sounds like a foreign word those rare times when it does come out of my mouth, because no matter how many times I’ve listened to “Drug Dealers Anonymous” today, I will never be entirely of the rap culture that I love. There’s nothing to lament here—it’s my own privilege, among other things, that distances me, and I’m not ashamed or guilty of that privilege. All it means is that I must, at times, show deference and acknowledge that there are things in the culture I don’t completely understand. Because, as easily as I always accepted the word in the rap I listened to, there was a time when I thought the guys I went to high school with sounded like complete idiots—referring to everyone and everything (white people included) as niggas. But it’s also true that they only sounded that way because I didn’t grow up hearing the word in the same way that they had. Now, many years later, I understand that it takes a certain amount of black respectability politics to label other blacks ignorant for using the word. And, perhaps more importantly, dismissing the so-called ignorant shit (to pay homage to one of my favorite Jay Z songs) when you’re outside of a culture, is perhaps the most ignorant shit of all.

In the few moments that I had to address this issue with my son, abbreviated versions of these thoughts ran through my mind. I finished conditioning my hair and took my time heading downstairs. I sat down, turned off the TV and I told my son that the word is complicated; that it can mean a good thing (sometimes, I told him, it is something friends say to each other) and it can mean a bad thing (I reminded him about how we went to the library to read about the Civil Rights Movement; I asked him if he remembered when we talked about Baltimore). I told him I understood what he meant, when he said he thought he was complimenting his Dad, but that he didn’t know the word well enough to use it… yet. It felt odd to say it—to suggest that one day he might want to use it, and it might be appropriate, and we could talk about it again then. But it was the most honest thing I could offer up, still in a bit of shock and trying to process it all.

Like moms everywhere, I’m wondering now if I screwed it up. Should I have waived it away with a simple, “Don’t say that word,” rather than bringing up the Baltimore Uprising (especially considering how sad he got the last time we talked about what it can mean to be a black American)? I probably did screw up, a little. But one of the best things I think any parent can do today, in this very strange America we live in—one that is as defined by Donald Trump’s success as it is by Barack Obama’s—is to talk about mimicry and appropriation—and how class, culture and race factor into those things, even when you’re talking about two kids, who look similar and come from similar socio-economic backgrounds. Two kids can live in the same apartment complex, like my son and his friend, and come from very different cultures. One kid might be of a particular culture, while the other is simply mimicking it.

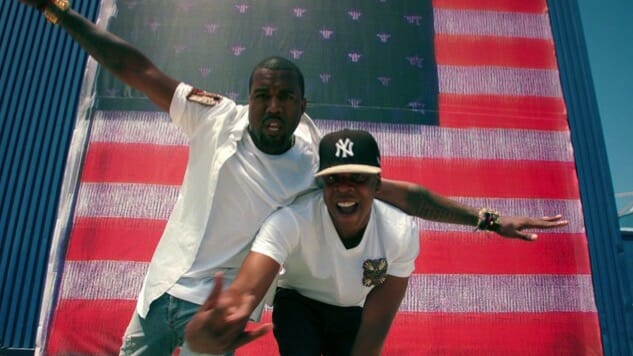

And as much as I’m terrified to think of the next fun trick my son’s friend might introduce to him on the bus ride home or in the lunch room, I have to confess that, after surviving n-i-g-g-a, I’m looking forward to it too, in some strange way. After all, that kid too, sings America. And while his may not have been the exact song I wanted my son to hear at the time, I know how important it is for a child to be aware of the myriad songs that define this country and its many cultures—whether it’s “The Star-Spangled Banner,” “Lift Every Voice” or Jay Z and Kanye’s “Made in America”—eventually, he’s going to need to know them all.

He may not ever be of the rap culture, enough for the word nigga to flow from his lips (and, no, that’s not what I want for him anyway), but he will know what it means to be a part of the very complex, patchwork quilt-like black American culture. It’s a culture that doesn’t start and end with nigger and nigga, but does I think, demand an understanding of the history of both words and the people who have been most effected by them.

These are such big lessons to teach, and like so many black moms everywhere, I’ll unpack them in bits and pieces throughout my son’s life, as the time calls for them—whether I’m ready or not. Most times, I suspect, I won’t be ready. These kids—our kids—they have to grow up so fast.

Shannon M. Houston is a Staff Writer and the TV Editor for Paste

. This New York-based writer probably has more babies than you, but that’s okay; you can still be friends. She welcomes almost all follows on Twitter.