Open Mike Eagle Picks Up the Pieces on Neighborhood Gods Unlimited

The West Coast rapper’s latest is a record about being split into pieces: selfhood as a broken phone screen, a reflection refracted in dozens of directions, a pile of black glass scattered across a city street, a horde of half-finished demos now lost to the void.

It has been 15 years since Open Mike Eagle declared he had seen the future on his debut solo record, 2010’s Unapologetic Art Rap, before warning: “If my premonition’s right, this is a demolition site.” Looking back at that song (“Helicopter”) from our vantage point in 2025, Mike’s once-parodically-grim predictions of bosses fully replaced by “mean computers,” terrorists transformed into gangs of “internet jerks,” and a society-wide inability to even take a shit without a keyboard at hand “to text on” feel more than a little prescient—holding not just a kernel of truth but a jumbo-size $14.99 AMC popcorn heaping of it. But at the time, the Chicago-turned-California rapper was so horrified by the thought that “every one of us” might soon be “living in [technology’s] reach” that he spent the chorus announcing “I’m getting the hell up outta here via helicopter / If I have to I’ll borrow Psycho’s helicopter / … / The only way up outta here is via helicopter.”

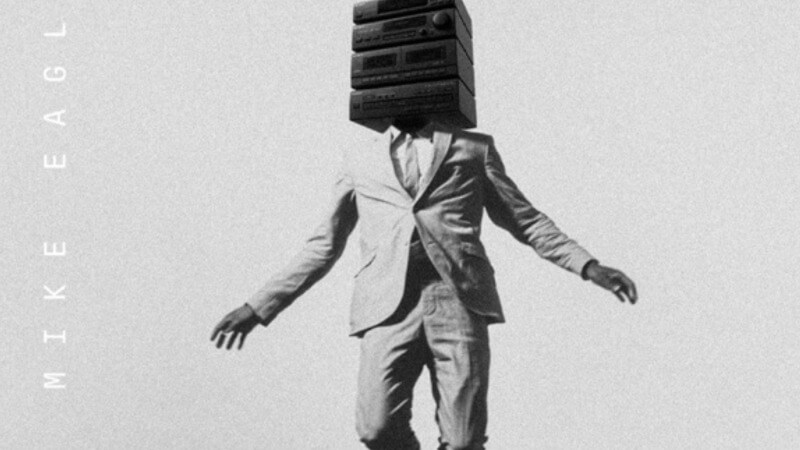

Ten albums and 15 years down the line, it appears Mike was not, in fact, able to talk Psycho into facilitating his escape plan. Tragically, in the absence of a helicopter, the coiner of “art rap” was stuck Earth-bound with the rest of us, unable to stop that future from arriving, or even to remove himself from it—and that’s never been more clear than on his latest release, Neighborhood Gods Unlimited. On its cover, Mike floats alone in a gray subspace, his own head replaced by a massive eBay-bought stereo, as if to say: forget merely “living in technology’s reach;” these days, we’re living in technology.

Critics are suckers for a throughline. We love to reconstruct an artist’s discography in the vein of a bildungsroman: the Boyhood-ification of a young voice, learning and growing in public, maturing as both an artist and person with each release. With ten solo records now under his belt and well over a decade on the scene, it would be tempting to hear Open Mike Eagle’s catalogue that way too. But, then again, he was already nearly 30 when he released Unapologetic Art Rap—already too skeptical, too self-aware, to play the naïf in some music journalist’s tidy narrative of self-actualization. That’s not to say there’s no growth, no evolution, across his releases; far from it. On the contrary, I’d argue that there actually is a bildungsroman narrative latent within his body of work, and it’s one that has grown more intentional and central with each album. It’s just that the subject of that coming-of-age story is not Mike himself, but the internet.

Listening back, it’s startling how well his records trace its rise—Open Mike Eagle plays the bemused outsider on Unapologetic Art Rap, shaking his head at the “junior rumors on my new computer screen,” but soon becomes the self-admitted endorphin addict “staring at my phone / wondering how endorphins travel via screen” on 2016’s Hella Personal Film Festival. The next year, he spits the memorable proclamation of “Your phone’s the new ark of the covenant” on Brick Body Kids Still Daydream, a claim that reaches its logical and devastating conclusion by 2020’s Anime, Trauma, and Divorce, when Mike (semi-jokingly) blames his divorce on “tech shit” and “Netflix”—specifically, on a Black Mirror episode critiquing a fictional couple’s relationship (both to technology and to one another) that hit so close to home it destroyed his own. The stereo-head from Neighborhood Gods Unlimited even made its debut two years ago, on the cover of 2022’s Component System with the Auto-Reverse—but there he sat outside, the greenery and tables behind him a stark contrast to the gray void he hovers in now.

Open Mike Eagle’s discography, read as a whole, feels almost like a reluctant historical document of the adolescence of the internet rendered in miniature—from irritating novelty to totalizing force. That doesn’t mean, though, that his work feels detached or clinical. If anything, his hyper-personal writing, steeped in self-deprecation and a kind of everyday melancholy, has always made his observations sharper. He didn’t set out to capture technology, but humanity—and it just so happens that, along the way, the two became indistinguishable. His dry wit and vulnerability make him an ideal chronicler of this shift: someone who can not only chronicle the mundane but give voice to the often embarrassingly intense emotions it produces. Someone who can admit that an event as banal as breaking their phone left them “in mourning for the portion of my brain that has to grab the words before they circle down the drain,” and still find a joke in the wreckage.

Neighborhood Gods Unlimited takes all of those questions—about where “we” end and the technologies mediating us begin—and turns them into the album’s central metaphor. It’s a record about being split into pieces: selfhood as a broken phone screen, a reflection refracted in dozens of directions, a pile of black glass scattered across a city street, a horde of half-finished demos now lost to the void. That’s not my metaphor, but Mike’s own, impossible to miss on the aptly titled “ok but im the phone screen,” where he grieves the parts of himself—the voice memos, the notes, the to-be-songs—that instantaneously evaporated the moment the phone hit the ground, lost forever because he forgot to upload them to the cloud. (In a great, intentionally facetious moment, he compares the incident to RZA’s infamous, devastating studio flood: “It’s like that but, like, less- less devastating”). And as the title cheekily informs us, Mike is not just the bereft but the bereaved: he is the cracked screen he’s grieving.

That concept threads throughout the entire record. A sampled voice at the end of the opening song, “woke up knowing everything (opening theme),” asks, baffled, “I saw the man broken, how he put his self together?” Both “contraband (the plug has bags of me)” and “mirror pieces in a leather bound briefcase” provide potential answers to that all-important question, but not good ones. On “contraband,” Mike imagines discretely bargaining with a local dealer to buy back the chopped-up slices of himself making rounds on the streets: “Bought myself back in plastic bags / Let’s call it contraband.” But even after scoring that fix, it doesn’t take long for Mike to find himself fiending once more. In fact, the end of the next song, “almost broke my nucleus accumbens,” is overtaken by a last-minute coda consisting solely of Mike pressing, over and over, “How do I get some more me?”

A few songs later, “mirror pieces in a leather bound briefcase” reframes the transaction as corporate rather than illicit, selling prepacked identities for profit rather than meaning. That track’s final moments are a fun-house mirror image of the “nucleus” coda, introduced after an identical burst of television static and pseudo-ad-reads, but sparse and dismissive rather than pulsing and insistent. Over a dull, repetitive clicking noise, Mike provides reassurance in a monotone: “We got that you for you.” Towards the latter half of the record, though, the question shifts somewhat, moving from “How do I find the pieces of myself?” to “Wait, what would I do with these pieces even if I had them?” By “rejoinder (burning the last puzzle piece),” the external search has been consumed by the internal one, with Mike asking point-blank: “Is it me if I’m all split up? / Do the pieces contain the whole?”

Based on Neighborhood Gods Unlimited, I’d argue that, at the very least, they reflect it. Across the record, these disjointed remnants are in constant conversation with one another, and a “whole” does emerge from these still-disparate fragments. This in part due to the concept of the record, borrowed from a shelved TV pilot Open Mike Eagle once envisioned, titled Dark Comedy Television (a reference to the name of his third record), giving those fragments a kind of narrative scaffolding: the entire album is presented as a scrambled hour-long broadcast from a failing cable network so close to going under they’ve been left no choice but to shove all their programming into 60 minutes. These segments seem disparate, but they’re on the same channel, bound by the same ads and producers—and those scattered shards may never fit neatly again, but each one still reflects the same face.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-