Senegalese pioneers restore luster of cosmopolitan Afropop classics

“The Black Atlantic” is the term black British scholar Paul Gilroy coined to convey how the Atlantic Ocean has shaped the growth of black culture and identity. The ocean, Gilroy argued, hasn’t so much divided black culture as it has unified it. From the days of slavery to the anti-colonial movement to the dawn of globalization, black arts, ideas and politics have developed at least as much through movement and exchange back and forth across the water as they have in specific locales.

Music is an arena in which this constant process of exchange has been especially sophisticated and clearly discernable. It isn’t just that Africa supplied the raw materials of rumba, mambo, jazz and blues. It’s also that, over time, African musicians have imported these musics back as finished products, only to reinvent them anew in a kind of organic cultural remastering.

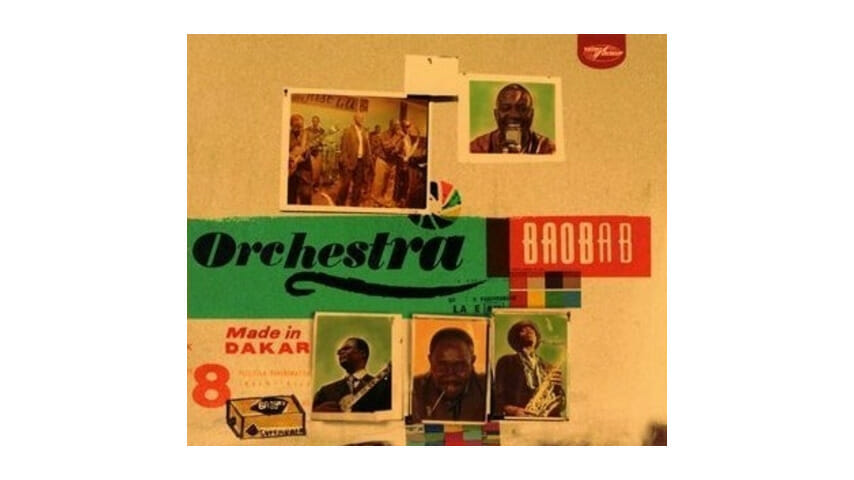

The lost/found story of Senegal’s Orchestra Baobab—which became a West African institution in the 1970s with its Dakar-inflected Afro-Cuban fusion—is an object lesson in Black Atlantic culture creation. It’s also a cautionary tale about the fragility of art—had it not been for the group’s near-accidental rediscovery by British world-music impresario Nick Gold, its sound might’ve been missed by everyone but those fortunate enough to have visited Dakar’s elite Coralia Club Le Baobab, where the group once served as house band.

But instead, Baobab is experiencing a comeback that was launched in 2002 with classic reissue Pirates Choice and a new disc, Specialist in All Styles. This renaissance continues with Made in Dakar, the luminous new album that finds the group interpreting—with undiminished vitality—a mix of repertoire items and new tunes. Out on Gold’s prestigious World Circuit label, the record also enjoys the support of Youssou N’Dour, the Senegalese superstar whose studios hosted the recording sessions and who appears as a guest vocalist on “Nijaay.”

But if N’Dour’s contribution and some of the old songs’ new arrangements introduce the hard funk of contemporary Senegalese pop genre mbalax, Made in Dakar is at its heart a throwback album. From the easy rumba of love song “Aline” to the pure Cubanismo of “Ami Kita Bay,” the sound is effortlessly groovy and deliciously mature, the kind performed, as Baobab’s members do, with perfect vocal harmonies and coat-and-tie stage dignity.

More than that, it’s also a direct conduit back to the kind of Pan-African sensibility that marked the independence generation—those who felt the hopefulness of decolonization before global economics and domestic political difficulties moved the mindset, in much of Africa, toward one of crisis and survival. In the polyglot African-unity spirit of the ’60s and ’70s, the lyrics of Made in Dakar are sung in Wolof, French and Portuguese Creole, and the themes include an homage to Amilcar Cabral, a fondly remembered Pan-African revolutionary.

Other songs carry the social messages and behavioral advice common in much African pop (“Nijaay” is about finding harmony in marriage), draw on the tradition of praise-singing (“Pape Ndiaye”) or nod to life’s mystical dimension (“Sibam,” which refers to the trance-like condition induced by a sorcerer’s spell, doubling as a metaphor for dancing at a hot party).

Nothing in this bill of fare, or in the band’s overall aesthetic, qualifies Orchestra Baobab as a progressive or edgy act. This is grown-folks music with a built-in nostalgia that makes it inherently conservative, especially when you consider the band’s origin: Le Baobab was founded in 1970 by Senegalese government officials as a place where the country’s new national elite could gather and socialize, and it was probably more accessible to well-heeled European visitors than the Dakarois hoi polloi.

After the band dissolved in 1985, its members went on to wholly respectable, urbane careers: lead guitarist Barthélémy Attisso, for instance, is an established attorney in Lomé, the capital of his native Togo, while another bandmate is a college professor.

But for the last five years Orchestra Baobab has been a working band again, with regular Saturday gigs at Dakar club Just 4 U. This not only gives Made in Dakar an in-the-moment energy that differentiates it from a more conventional reunion album—it also means that the members of the group have become, once again, active participants in a highly fertile local cultural scene where their brand of old-guard Afro-pop prospers alongside local mbalax and a growing trend toward hip-hop and electronica.

The re-emergence of Orchestra Baobab is just one among several recent instances where veterans of the ’60s and ’70s have had the chance to revive the uniquely cosmopolitan and historically significant West African music of that time, not only for the benefit of Western audiences but also for younger ears at home. (Congo’s Kekele and Guinea’s Bembeya Jazz National are two others that come to mind.)

And if Baobab’s hefty marketing support owes much to the world-music biz’s mostly white Western gatekeepers (the influential Gold was also an instigator of the Buena Vista Social Club project), this does not take away from the value and enjoyment of seeing this seminal act back on the scene. With any luck, the band’s success will spread to other near-forgotten African-pop pioneers, of whom there are sadly plenty.