Wherever Pete Yorn Goes, There He Is in Hawaii

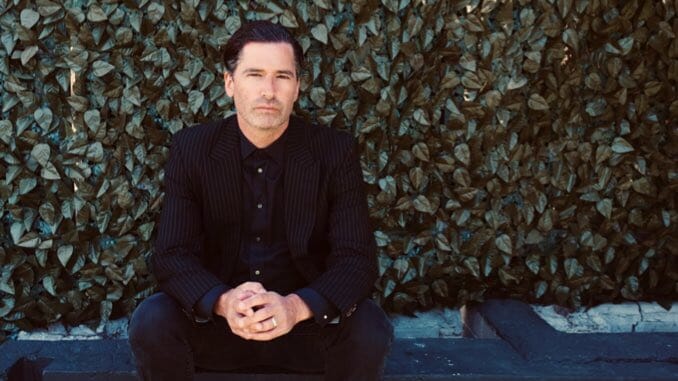

Photo by Beth Yorn

Pete Yorn had plenty on his pandemic platter, project-wise—he wasn’t initially looking to pile on more. The New Jersey-bred, Los Angeles-based tunesmith could have easily rested on the laurel of his self-released 2019 achievement, Caretakers,” confidently co-produced with his keen-eared studio accomplice, Jackson Phillips (aka Day Wave). Instead, he got busy in early 2021 with a Bandcamp-proffered covers album dubbed Pete Yorn Sings the Classics, collaborating with another production chum, Marc “Doc” Dauer on unique versions of some of his all-time favorites, including unexpected choices like Henry Mancini’s “Moon River,” Roxy Music’s “More Than This,” The Beach Boys’ “Surfer Girl” and even the Diana Ross standard “Theme From Mahogany (Do You Know Where You’re Going.” He also tested out his warm, woodsy goth-folk warble on suitably edgier material, such as “Here Comes Your Man” from Pixies and “Ten Storey Love Song” by Britain’s Madchester-defining Stone Roses. Additionally, he felt compelled to celebrate the 20th anniversary of his dazzling 2001 debut musicforthemorningafer—which had broken his bass-thwapping, punk-spirited, occasionally vocoder-distorted sound via the irresistible hits “Life on a Chain,” “Strange Condition” and “For Nancy (‘Cos it Already Is)”—with a new The Rooftop EP, featuring “Rooftop,” a previously unreleased chestnut from those landmark, garage-scrappy sessions two decades earlier, plus three other cuts.

Yorn, who turns 48 next month, was also quite content just spending slow-motion lockdown time at home with his wife, photographer Beth Kaltmann, and their inquisitive daughter Elle, now six. He never imagined that there was an entire new record, his ninth, which is now optimistically titled Hawaii, ricocheting around inside him, just begging to be released—which it is, completed, today, June 17. And it would turn out to be one of his most memorable collections, fluidly tapping into that touchstone MFTMA energy (on “Blood,” “Never Go” and the jangly lead single “Elizabeth Taylor”) while simultaneously skewing almost Vince Guaraldi Trio-forlorn in some places (“Further,” “Ransom,” “Stay Away” and a oblique-chorded “Miss Alien”). It’s a deft, dazzling display, revealing a songwriter firing on all inventive six, 20 years into his risk-taking career. To hear him tell it, he didn’t really have much of a choice in the matter—he was simply compelled to make Hawaii, once he discovered that his old cohort Phillips had retreated to the secluded California desert like he and his family had.

Initially, the two musicians kept missing each other. Then: Pandemic poetry. “Because we were in such a flow with Caretakers back in January of 2021 that we had already made a couple of new songs that we put out, ‘The World’ and ‘Jeanine,’” Yorn recollects. “But when we finally got back together after not seeing each other for so long, and not being able to work on music? It was in late April, early May of 2021, going into the studio, we were so excited just to see each other, we were both like, ‘Oh my God! Is this crazy? Are we actually back?’ And we just clicked right in to doing what we do.” The first song from the first session was “Ransom,” a pensive keyboard processional Yorn wrote on a rickety old piano that had once graced his childhood home back in New Jersey. And the hits, as they say, just kept right on coming. “So a lot of the energy of this record is two guys just being so excited to be back working together, after some kind of forced separation which we’d never dealt with before.” He chuckles at the dark irony. “I mean, no one had, really, right? So I learned that I no longer had to be so precious about things.” The life lessons, like the inspired new material, just kept on arriving, too. And he was happy to run them all down for Paste …

Paste: There seems to be a forlorn feeling of regret coloring Hawaii. Or am I wrong?

Pete Yorn: There’s a lot of reflection that I typically do. But I feel like everyone’s anxious to move on from the pandemic and all that, but it’s impossible to trace the lineage of this record without just going back there. And the birth of it was definitely during major early quarantine, lockdown, kind of unknown days, where—looking back at it—it’s like, “Whoa!” It was unprecedented for any of us, you know? And so there was a feeling of isolation, for sure. We packed up and just split into the desert, me, my wife and my daughter. And my wife saw it coming early, in December of 2019. She’s always liked sci-fi movies and post-apocalyptic movies—she’s like a junkie for that stuff. And she kept saying in early December, “Dude—there’s this thing going on in Wuhan. Check it out—I’m telling you, this is real.” And she’s not an alarmist at all. But she said, “They’ve locked down this city—I’m telling you, something’s going on!” So by Feb. 15, we left for the desert. Because where we were living, which I had never minded before, our apartment was on the same block as the emergency room at St. John’s hospital in Santa Monica, and there would be ambulances rushing by. And I never minded it before, and then all of a sudden with the possibility of this contagion, it just became really claustrophobic and felt weird. And you didn’t know if you could just get it walking outside. So I said, “We’re getting the hell out of here!” And we bailed and went to the desert. And it ended up being the hottest summer on record in Palm Desert, California. If you look it up, literally! 2020—the hottest one on record, and the one that we stayed out there for.

And I remember feeling something very clearly one day. There were times that I would feel just happy to be away and be with my family, and the simplicity of it, and my little girl was still four or five or six at that point—it was just this super-family time, and no excuse to really have to go do anything, other than kind of just keep it simple. And there would be weeks that went by where I felt pretty content, but then I’d have a few days where I’d start to feel really restless and claustrophobic. And it was one of those days where I was just sitting out back, by myself, and my little girl comes out and goes, “Daddy—this could be Hawaii!” Because she loves Hawaii, and we’d taken her there a few times, and it had become her favorite place. And it was such a simple thing for a kid to say, but it just made me think of … the state of mind. For some reason, it just resonated so hard, and I was like, “I’m gonna name my album ‘Hawaii.’ Whenever I make an album, I’m naming it ‘Hawaii.’” Because it evoked so much to me, as this magical place to escape to. Especially during the pandemic, if you felt like you just wanted out, somewhere you could fantasize about, like, “Where could we go where we could live normal again, and just not have to feel this loss of our way of living?” And I felt like Hawaii evoked this chance for escape, this chance for freedom.

So the record itself has nothing to do with literal Hawaii. And in fact, I will tell you that the album cover is a pool—it’s not even in Hawaii. It’s in the San Fernando Valley, and there are glitches in the top of it, because those are the glitches in The Matrix. And a lot of the songs are different things, thematically, but you’re dealing with isolation, you’re dealing with loss, unrequited love. But in a lot of it, you’re dealing with archetypes, as well, like Hawaii as this archetype in our mind of this perfect place. But ultimately, wherever you go, you’re stuck with yourself, you know? And you bring your own baggage. I’ve been to Hawaii before, where I’m looking forward to a vacation, and I’ve had great times there, and I’ve had shitty times, where I’m stuck in my own head and not able to enjoy it. So it’s this idea that, wherever you are, if you could find this peace that lives within, then you can actually have a good, purposeful existence, and you don’t have to go to Hawaii, if you know what I mean.

Paste: Later did you actually, finally say, “Well, let’s physically go to Hawaii? Why not?”

Yorn: We did. We went for the month of February 2021. We were able to go for a month. And I didn’t want to go anywhere, but my brother [Rick Yorn, noted Hollywood film producer] talked me into it—he was like, “C’mon! It’ll be great! We’ll live in a house together and it’ll be fun!” And I was even nervous about that. But in hindsight, it was the best thing, because when you’re in with your five-year-old for months and months—it was just me and her and her mom, and I’m cleaning toilets, mopping floors, and coronavirus reports kept coming in until you don’t know if it’s gonna kill you or not at that point, you know, those early days where everyone was just freaking out about things. Everyone has their own tolerance level, but those early days were a little spooky. And I was doing livestreams from the desert—they’re all on my Instagram, there’s like 10 of ’em. But I went to Hawaii, and I was so happy I went—it was amazing. It was all pre-vax, but when I got back the vaccines became available, and I got mine at the end of March.

Paste: The delicate Hawaii album closer, “Stay Away,” feels like one of the most brutally honest songs ever. And I’m not even sure what it’s about.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-