Boots Not Required: How Line Dancing Became the Internet’s New Favorite Hobby

From TikTok FYPs to the dancefloor, everyone seems to love line dancing right now—but the country dance style created its niche a long time ago.

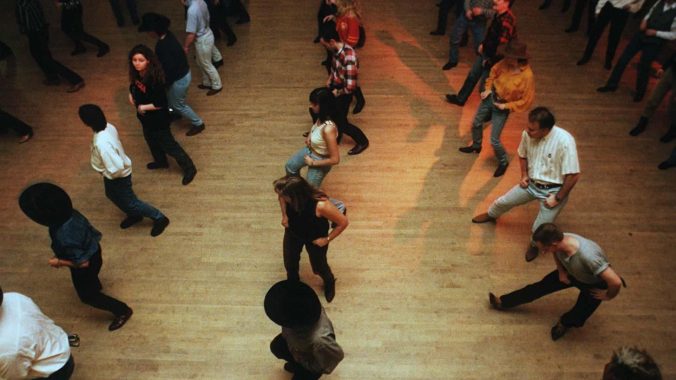

Photo by Edward Webb/Shutterstock

“Delighted confusion,” Jordon replies when I ask him how he would describe the atmosphere on the expansive wood-paneled floor of the Brooklyn Bowl. On the stage behind him, California-based duo Stud Country—a weekly queer country and line dancing class started by friends Bailey Salisbury and Sean Monaghan—teach a new sequence of choreography to the attendees of their line dancing event. “And also an eagerness to be wrong,” he adds on. Stud Country has already hosted a few parties like these in New York and even more in California. Salisbury and Monaghan, together, aim to “honor the rich history of LGBTQ cowboy culture” and pay homage to the importance country dancing holds in LGBTQ spaces. Jordon (who wishes to only go by his first name) surveys the crowd at this particular event on the night of January 23rd, the mirth in his eyes glinting in the disco ball’s light while he watches some quickly pick up the steps while others stumble their way through. He’s soaked in sweat—despite the cold temperatures outside and the fact he’s only wearing a black tank top, his red plaid shirt tied around his waist—after just learning the dance himself and running it a few times.

His restless, excited energy is reflected in just about anyone who’s ever line-danced, by people who get bit by the bug—and it’s a bite that sparks an excitement to learn steps and, though you probably won’t hit them right away, you’ll still thoroughly enjoy yourself trying. Personally, my bug bit me via TikTok. Sandwiched in between pasta tutorials and lip-synching videos, my For You page served me an iPhone video of a plaid shirt-donned and Stetson-wearing man line dancing, with gusto, to Ed Sheeran’s “Shivers” in a dimly lit bar. “Huh?” I thought, caught off-guard. I kept watching as the video looped again, mesmerized by the easy flow and flair he moved with. “It’s not what you’re typically used to seeing, so it stops you in your tracks,” says Kevin Hofmeister, better known as DJ John Stamps. Hofmeister also created and serves as the creative director of Boot Scoot USA—a touring classic country DJ party focused on “disrupting the stereotypes that alienate potential country music lovers” who host country nights at bars across the U.S.

It seemed to me line dancing, something I’d only ever interacted with at wedding receptions when moving to the “Electric Slide,” was becoming modernized with pop songs and a new fixation from Millennials and Zoomers. The “line dance” tag on TikTok hosts thousands of videos with hundreds of thousands to millions of views. A quick scroll through the results and you’ll be flooded with clips of people grooving to country songs or, even, more contemporary tunes—like Ke$ha’s “Take It Off” and Nickleback’s “Burn It To the Ground.” For people in cities without a regular honky tonk bar to spin and stomp away at, there are groups like Boot Scoot USA or Stud Country that travel around to host widely attended country-western-themed parties. And while jeans, a t-shirt and sneakers are acceptable attire at these events, people also jump at the opportunity to dress in their best cowboy or cowgirl boots, low-slung tight jeans and bows—think “Brokeback Mountain just went to the club.” To put it simply, line dancing is in its “yassification” era. Though, I’d soon discover that zeitgeist captivating a younger generation has steadily flourished in some communities, particularly the LGBTQIA+ community, for decades.

Hofmeister has played a small part in this growing popularity. He first started Boot Scoot in 2019, but the Indiana native’s love for country music traces back to his childhood. As a DJ, he routinely jumped at the chance to spin country records. When a line dancing instructor showed up to the first ever Boot Scoot event he hosted at an Indianapolis bar and started directing attendees with choreography, Hofmeister quickly noted the unbridled joy everyone seemed to experience as they moved in unison and realized that “was what the night should be about.”

“The event would have been fun without him, but [the line dancing] just brought this fun, campy energy,” he continues. Since then, Hofmeister along with his co-creator and designer Kyle Nagy (also known as KNags) has created an inclusive dance night that aims to remain approachable any experience level while making everyone feel comfortable by bringing out guests from Dolly Parton drag queens to musicians pushing the envelope on country music—like Lola Kirke.

While collectives like Boot Scoot and Stud Country help make line dancing more accessible and heighten its popularity, that doesn’t mean people were never interested in the style to begin with. All styles of country-western dancing have long been danced in (and out of) your average honky tonk American bar. When talking about this cultural resurgence, it’s important to understand line dancing isn’t the entire culture. Rather it’s a niche within a broader subculture of country-western dancing. Oftentimes, if you attend a line dancing night, you can also expect to see some partner dancing as well. Once everyone’s done their final stomp, spin or clap, and everyone applauds each other for a job well done, the floor will clear out for a few songs as everyone gets another drink. A few pairs will likely remain and they’ll suddenly start seamlessly swinging together around the room, their feet speaking a language together even if they’ve only just met. That’s country-western partner dancing. But consider country-western as the umbrella and, under that umbrella, exists line dancing, too. But then there’s also a whole other world of partner styles—including two-step and both East Coast and West Coast swing, among others.

“I don’t think people realize how many different styles of couples dancing there are in the country world,” says George Blick, owner of Standard Western and who you also might find on stage at the Nashville Palace some nights. The Palace lives up to every expectation you have for a honky tonk bar—wood paneling, disco ball, a large dance floor the bottoms of your shoes stick to and line dancing, all taught by Blick. Except, his microphone-d voice echoing out across the room doesn’t possess the Southern drawl you might expect but, rather, the dulcet tones of a Welsh accent. Blick has been a fan of line dancing since his childhood in the U.K., when his nan and auntie started taking classes. “[They] would come home from class and they’d just be so excited about learning the latest dances,” he reminisces.

Soon, Blick started taking classes himself and entered his first competition at 11 years old. While he states many saw line dancing as something for old people when he first started dancing, it still maintained enough popularity in the late ‘90s and into the 2000s for him to compete and even land him on the cover of a line dancing magazine. Country-western dancing especially maintains a foothold in the LGTBQ community, something Los Angeles-based DJ Rick Dominguez can speak volumes to attest to.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-