St. Vincent Crawls Through the Fire

In our latest Digital Cover Story, Annie Clark discusses her decision to self-produce for the first time, how her relationship with the guitar has changed 17 years into her solo career, and what it means to surrender to a song’s survival on her seventh and latest album, All Born Screaming.

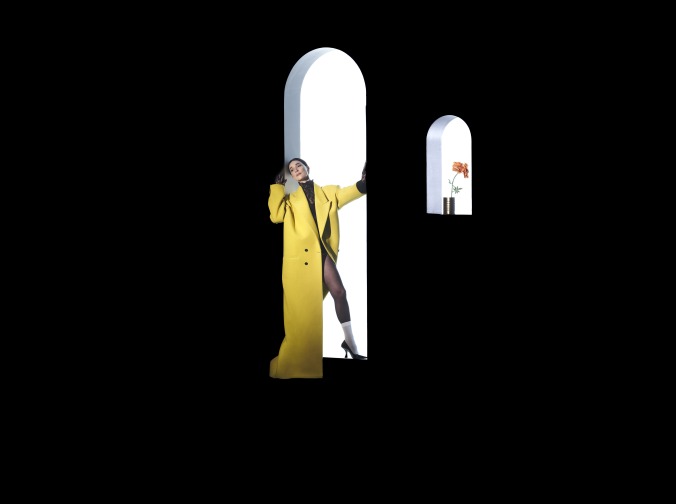

Photo by Alex Da Corte

It was 2014 and Nirvana had just been elected to enter the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. I was relatively new to their music, having discovered it on YouTube sometime the year before and, naturally, became obsessed with their three studio albums and various live concerts (many of which I would, eventually, procure on DVD). Though many—and I mean many—Nirvana fans had spent more than 20 years waiting for that moment, I found it endlessly cool and perfect that I got to jump on the bandwagon mere months before their musical genius was enshrined in rock ‘n’ roll history forever. Soon after came the Rock Hall’s induction ceremony, which featured the remaining members of Nirvana—Dave Grohl, Krist Novoselic and Pat Smear—performing a litany of their most iconic songs with the aid of various women anchoring the vocals (an ode to their late frontman Kurt Cobain, who routinely and vocally championed woman-fronted music during his time with us).

Sonic Youth’s Kim Gordon sang “Aneurysm,” Lorde sang “All Apologies” and Joan Jett sang “Smells Like Teen Spirit.” But to me—nothing but a 16-year-old kid reveling in the magic of seeing their new favorite band’s reunion on live television—I still remember how transfixed I was by Annie Clark’s rendition of “Lithium,” a powerful performance that didn’t attempt to capture the raw-throated vocals of Cobain or the original convergence of Novoselic’s pop basslines with the former’s down-tuned riffs. Instead, it became its own momentous wonder—powered forward by Clark, whose fabled guitar playing and mercurial talent under the name St. Vincent has now anchored a beloved, crucial sector of rock ‘n’ roll for 17 years. In April 2014, when she took Barclays Center stage in her native borough of Brooklyn, she had recently released her self-titled fourth album—one of the best art-rock and pop albums of the last decade—and, though St. Vincent’s impending Best Alternative Music Album Grammy win wouldn’t come for another 10 months, Clark taking the stage with Nirvana was sublime punctuation on a seven-year run of bang-on, generational sonics.

“Full-circle” is a phrase that comes to mind often when exploring the palette of Clark’s seventh and latest St. Vincent album, All Born Screaming. Upon the release of lead single “Broken Man,” we are greeted by a mirage of industrialized, metallic drumming. Mark Guiliana and producer Cian Riordan lent their pounding to the mix, but the name at the center of the track’s percussion just so happens to be Dave Grohl. “I remember being nine years old and my best friend’s cool older brother played Nevermind on the tape deck, as we were on the home-built halfpipe trying to learn how to skate,” Clark says. “I remember that feeling. I remember just the world stopping when I heard Nirvana. Getting asked to help be a part of their legacy [in 2014], I thought that was a full-circle. But, then, it turned out there was another circle—which was asking Dave to play on my record. I think the point of it all is to be generative, and to make things generate that spark in other people and other artists for generations. And then, what they make does the same thing and you have this music—this art—that actually gives life forever and ever and ever and ever and ever. Amen.”

After her last album, Daddy’s Home, came out in May 2021, Clark did what any musician would: see their psychological thriller film (in Clark’s case, it was The Nowhere Inn, which she co-wrote with Sleater-Kinney‘s Carrie Brownstein) hit theaters and contribute to the Minions: The Rise of Gru soundtrack. Clark, to my delight and likely that of many others, gave Lipps Inc.’s “Funkytown”—a song that is championed for its all-time great bassline, revered for its impact on post-disco and, possibly, even reviled for its overuse in film and TV—a proper St. Vincent makeover. If any hate towards Lipps Inc. is sent their way, she won’t have any of that, either: “That is a great song. I would like to go to Funkytown. I’ll be the first in line,” she says.

The era of Daddy’s Home couldn’t feel farther away than it does right now. Ever the matriarch of chameleonic alt-rock, Clark, now 41, has all but ditched the Candy Darling-esque alter-ego she reveled in three years ago. When she did press back then, she would arrive on camera wearing a patterned headscarf and tinted aviator sunglasses; when she dropped Masseduction four years before that, journalists had to enter a neon pink-painted box if they wanted to ask her questions about the album. But this time around, there’s no performance involved in Clark’s presence on our Zoom call; no grandiose wardrobe to flaunt or skyscraping measure of method-acting to embolden. She walks around her house with her camera off, filling the spaces between her thoughts with various clatters. She even pauses our talk to answer a call from her sister, because she worries that “when anyone calls, it’s bad news.” It’s clear, quickly, that I am not speaking with St. Vincent. This is Annie Clark, and she’s left the vainglory and theatricality behind—for now.

The tapestry of All Born Screaming’s visual imagination, too, suggests that this is the most naked Clark has ever been on a record. Even from the title, there is a very deeply embedded conversation around the pain that we’re born into—or, even, the grief that comes with rebirth, how we come into this world with no language. On tracks like “Flea,” “Big Time Nothing” and “Violent Times,” there are sea-change tempests afoot. All at once, this era of St. Vincent sounds like the St. Vincent of old and the Annie Clark of now. These 10 songs catalyze a metamorphosis; out of the ashes of Daddy’s Home comes a pensive, egoless Clark—who is now walking into the fire, seeing what’s on the other side and trimming away the fat for the sake of a song’s survival. All Born Screaming is, at long last, a proper, career-spanning time capsule harboring the flourishes of her greatest eras. Lounge, noise rock, baroque, funk, chamber pop, electronica—it’s all here and orbiting each other.

All Born Screaming marks a unique turn in Clark’s career: It’s the first St. Vincent album she’s self-produced, graduating from collaborations with John Congleton and Jack Antonoff and rupturing into a phoenix of creative control. The move was inspired by, as Clark puts it, the realization that there “were sounds in my head that, really, only I could render, because they were part of the whole story.” There’s nothing arbitrary about All Born Screaming, and every component—from the doomy, mortally-wounded lyricism to the bone-rattling instrumental gospel—exists in such a deliberate way that Clark couldn’t have possibly imagined outsourcing it.

“Being a producer, to me, is like having your full sonic personality and sonic footprint on everything. One of the things we strive for as artists is to be singular,” she continues. “You can hear one note and know that it is Miles Davis. You know people by their voice as an artist, and I wanted people to know me as a producer and know my voice as a producer—in the same instinctive way as with other things. Also, there are just places emotionally you can only go alone, when you wander into the woods and you’re like ‘There’s nobody but me who’s going to tell me that this is real, good enough, bold enough. There’s no one but me who’s going to say that and be that kind of filter. And that takes a new level of instinct and trust and faith and courage.”

Pulling the strings herself is not a new horizon for Clark. She’s been recording herself since she was 14, first on a TASCAM 4-Track, then early digital software and, now, in Pro Tools. “Recording myself has always been the way that I hear what I sound like, how I figure out what I think and how I arrange and think about music,” Clark says. She mentions being in the studio while making “Reckless,” All Born Screaming’s second track that unfurls the entire album into a sonic paradox—where Rachel Eckroth’s sinister B3 organ meets the flora of Clark’s sprawling, untreated vocals that were performed over 100 times. Like much of the record, “Reckless” is an example of Clark chasing perfection—but not the kind of perfection that answers to pitch and time. “It has to be raw and it has to be real,” she continues. “When you’re not performing it, you are it. You don’t have to be it. You are it. The only way for me to get there was to do it over and over again until nothing about it was false, nothing was performed. It just was because it existed, because it was real. There was nothing put on nothing, no vanity about it.”

And likewise, album opener “Hell is Near” took a long time to get right. It’s one of Clark’s most ornate compositions in years, arriving as her voice morphs into a cathedral before slowly crawling into a vibrant 12-string guitar melody via the cobblestone of Eckroth’s acoustic piano. “Some songs you grab by the throat and wrestle them to the ground,” Clark contends, “but then, there are some songs that just truly won’t reveal themselves to you, won’t open their arms to you—unless you come at them with a righteous, pure heart. ‘Hell is Near’ was one where I sang it over and over again. You have to be bare, you have to emotionally be there to sing it. Anytime I tried to put any sauce on it, anytime the ego crept in, the song would just fall apart in your hands. The way you approach material, you have to come correct. I always think of Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, where it’s like ‘only a penitent man shall pass.’ You have to just bow before it, sometimes.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-