If you were putting together a Dream Guest List for a rock-and-roll celebrity dinner, you couldn’t find a more memorable—or lively—addition than the legendary guitarist Steve Cropper.

He’d easily be the chatty center of table attention, having started at Memphis imprint Stax Records when he was only 20, writing and producing for a stable of R&B stars that included Otis Redding, Wilson Pickett, and Sam & Dave, and—with his longtime bassist cohort, Donald “Duck” Dunn—anchoring its house band, Booker T and the M.G.’s. His sinewy signature riffs have beefed up the work of Bob Dylan, Eric Clapton, Neil Young, Johnny Cash, Ringo Starr, Rod Stewart and Mavis Staples, to name only a few, and he’s been seen on screen (with Dunn, as well), as the backup group for John Belushi and Dan Aykroyd’s slapstick—but musically serious—The Blues Brothers movie, directed by John Landis in 1980. He also has a pink picture disc of Amii Stewart’s thumping 1978 disco version of his co-written classic “Knock on Wood” (“It went platinum, so that was really good,” he observes). So it’s pretty much guaranteed, any historic yarn other guests might have? This guy can top it.

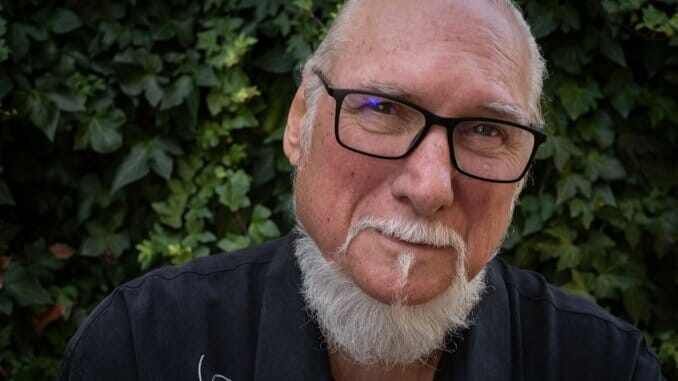

Walking through his spacious house in Nashville a few weeks ago, Cropper, 79—who was calling to promote his new solo set, , featuring his understated but assertive playing alongside the gruff, soulful vocals of Roger C. Reale—stopped by his office to survey some personal keepsakes. It houses his Grammys, Hall of Fame certificates (Songwriters, Nashville Songwriters, and, as part of the M.G.’s, the coveted Rock and Roll acknowledgement), and autographed photos of him with three U.S. presidents. “I’m looking at ‘em right now,” he reports. “There’s Daddy Bush—well I called him Daddy Bush—Bill Clinton, and I even had pictures taken with Obama.”

Naturally, he had an impromptu jam with the saxophonist-in-chief one night at a club called The Wolf’s Den in Connecticut—he can’t name the old Chicago blues number they played, he only recollects that the band was in the key of C, but the prez enthusiastically jumped in on B flat. Joining Cropper onstage was almost de rigueur for any serious R&B artist in the crowd; Donna Summer appeared out of nowhere one evening to lead him through a rousing rendition of “She Works Hard For the Money.” Another show it would be Sam Moore of Sam and Dave, for a rollicking take on “Soul Man.”

While considering a move to Sausalito in the early ’70s, Cropper was writing and recording with his chum Stephen “Doc” Krupka from Tower of Power in Oakland. “And one weekend, he said, ‘I want you to hear this new guy sing. So we went down to his tiny second-floor club with a super-low ceiling, and this amazing young guy gets up there and starts singing and playing harmonica and all that, and I met him afterward but I don’t think he knew who he was meeting. But do you know who he was?,” he asks, in his best Paul-Harvey, good-day voice. “Huey Lewis, so long ago that if he had The News on his mind, it was way back in his head somewhere.”

That was in December of 1988, when Orbison ate dinner with his mother, decided to lie down for a bit, and then had a heart attack that killed him at only 52. The bullet point? Carpe diem, reckons Cropper. Vita brevis. So if you can’t have dinner with him, he offers this tasty repast instead.

Paste: So even today, when you say, “Get off my lawn,” trespassers better listen?

Cropper: I sure hope my aim’s still good. When I was in L.A. recently, I went to a range, and I was really good. But I’m sure I could still do it. I have a theory about teaching people to shoot—I say, “You can hit anything you point at. Don’t have your mind on the South and point West—that ain’t gonna make it.” I think you can hit anything you point at. The problem is, usually the person’s pointing finger is their trigger finger. Well, put it down the barrel first and point, and then put it on the trigger—you’ll hit it every time.

Watch a Steve Cropper interview from 1984:

Paste: The Blues Brothers movie has been running a lot lately. And there’s this hilarious scene where a label exec buttonholes the duo backstage and declares, “Hey—I don’t bullshit! I’m president of Clarion Records. Here’s $10,000 as an advance on your first recording session. Do we have a deal?” Is that the way it was done back then?

Cropper: That was pretty far-fetched. I mean, maybe it happened that way. But that was the first time I ever saw it depicted that way. At Stax, you came in with a hit song and sang your butt off. And then you spent the rest of your life trying to follow up. That’s what we call a followup record—trying to get another one as good, or close to. And well, some people could, and some people couldn’t. Otis had 17 in a row.

Paste: And when you met him, he was just a kid?

Cropper: He was working for Johnny Jenkins and the Pine Toppers as the lead singer, but I thought he was the driver. But once I heard him sing, I just couldn’t believe it. I still can’t believe it—I listen to his records and think, “That’s Otis! Now, wait a minute!” He just made everybody sound different, sound better than they really were, I thought. He definitely made me sound better than I was.

Paste: But in The Blues Brothers, the band is all swaying dramatically onstage to the rhythm of each soul classic. Was that a part of your choreography back then?

Cropper: Maybe. Well, naw, it was all choreographed for that film, I think. Because every band we played with didn’t do that. And I’d never really watched that movie from top to bottom before. But the other day, my maids were here, and The Blues Brothers was on. And they got so into it, I let ’em just sit down and watch it. And whenever I was in there watching it with them, they’d yell, “Hey—there he is! There he is!” I was thinking, “Oh, man—I shoulda shut this damn thing off!” But I have to tell people that the Blues Brothers Band itself came out of Levon Helm and the RCO All-Stars. We did two albums and two world tours with him, so when they put the band together, I know that before that, Belushi had said, “If I ever put a band together, I want that band.”

We were playing at the Palladium for New Year’s Eve one time, and he happened to be there, so that’s what I remember him saying. And when Steve Martin said, “I’m doing these shows at the Universal Amphitheater, and I need you and Danny to open for me.” And Belushi said, “We’re standup, but we don’t do live standup comedy.” And Steve said, “Well, I don’t care what you do.” So John said, “Well, man, can we play music?” And he said, “Absolutely, if you want to!” And Belushi said, “Okay.” So they started putting a band together, and Tom “Bones” Malone was in it, and he told me that Belushi came to him and said, “Should we take the whole Saturday Night Live band?” And he said, “Well, we could. But let’s get (Duck) Dunn and Cropper, because they’re old road dogs. We’ve been out there with ’em for a couple of years and they really know the road.” And that’s how we got in there—thanks to Tom “Bones” Malone. And then Belushi remembered that he had seen us play before.

Paste: The weirdest scene is the band’s first concert song, with a huge audience that’s been cued not to applaud or even say a word. You guys are playing your heart out, and everyone’s just staring, quietly. That must have been weird to film.

Cropper: It was pretty weird. But the thing is, those people in that audience were all extras—they weren’t just called to come down and see a free show. So there was not a peep. Landis wanted to control that whole scene, and he did. And they got paid to do exactly what he told them to do. They were basically all extras. So I guess there’s a lot of extras in L.A.! They filled the Palladium with ’em—there was a bunch!

Paste: John Belushi had a decent voice—I’m sure you’ve heard better. But your band made him sound like a superstar.

Cropper: We got a lot of flak on that movie, Duck and I did. Basically, they were saying, “What are you two guys doing, working with these crazy comedians from Saturday Night Live?” And I was like, “Are you kidding me? Belushi had a band, was a drummer and a singer in a band for many, many years, and Aykroyd’s actually playing the harmonica! He’s not faking that—that’s actually who he is.” They just thought they were straight comedians. I said, “Belushi’s a great actor—he’d already done Animal House and some other stuff like Goin’ South before we did The Blues Brothers. But yes, he was a great actor. And the thing about Belushi was—or what I think made him so great, because I hung out with him a lot—he could say anything or nothing, and you’d laugh your butt off. He was just funny to look at. He was sort of like the fat guy in Abbot and Costello, Lou Costello. He didn’t have to say anything—he could just make a noise, and it was funny.

Paste: There was a nice documentary about him last year, R.J. Cutler’s Belushi, that revealed what a soulful, driven and just rock-and-roll guy he was at heart. He wasn’t scattershot—he knew what he was doing.

Cropper: Well, people don’t know this, but Rodney Dangerfield, of all people, used to tell everybody things in advance—tell the band in detail exactly when he wanted the drum to hit, or the cymbal to crash, and when he wanted you to do this or do that. Like, “I want everybody to laugh and clap when I say this.” He had all of it, the whole show worked out. But John did, too. And a lot of people don’t respect comedians—they see them as just thinking off the top of their head. And well, no they’re not. And somebody told me one time—and I did his show, but I dunno—Jay Leno, they say he had two and a half hours of material memorized, just totally memorized. He didn’t have to rethink anything, just two and a half hours, ready to go. And I think that’s pretty cool.

Paste: Looking back at Stax—and you started there at 20—were there ever jaw-dropping sessions where you thought, “Oh, my God! Who is this?” And, on the converse, were there ever any sessions where you thought, “Oh, my God! I just can’t make this guy or gal sound very good”?

Cropper: I don’t recall any. I mean, everybody wasn’t perfect. But I don’t recall any real bad sessions. There were some sessions that weren’t as good as others, when you listen back to ’em. But we still had to mix ’em as though they were Number One records. And I think some of the pop things that we got into for Hip Records and all were not near as good as some of the R&B records, obviously—they just didn’t have it. But they had us, and we put all we could put into every record. But it didn’t always turn out that way.

Paste: You said you learned to listen to each artist you were working with to figure out the perfect backing tones?

Cropper: My whole idea was always to just listen to it and go for it. Let God take over, and you just channel the notes—that’s all I can tell you. They’d say, “How do you come up with those licks?” And I’d say, “They just fall out of the ceiling—what can I tell you?” I know that real good musicians, they’re there to channel things—the notes are just sort of given to you, they just fall out of the sky, they just fall on your hands, and you go, “Wow! That’s a pretty cool lick! How’d I come up with that? I’ve got to re-learn that one!” And you don’t know at the time when something’s gonna hit and when it’s not. If I really took the time to listen, I’m sure that there’s things that we’ve cut where I thought the track was good, but yet the song or the song wasn’t all that great. You don’t think of it at the time you’re doing it. You think of it later, when you’re mixing it. And it’s usually somebody else’s song, done a certain way, in the way they want it, which is not always as commercial as the way you might do it. So it’s not the battle of the bands, but some people just have a knack for it, and others don’t. And that’s the way that we’ve treated the writers. I mean, there was something that Hayes and Porter had that nobody else had. And We Three were great writers—Homer Banks and Bettye Crutcher and Raymond Jackson. They came up with a lot of hits, and Bettye and I wrote some hits. We wrote some good songs—“Move ’Em Out,” for one, and I think that was for Delaney and Bonnie.

Paste: Looking back, you got seriously into Gospel and church music. Did you attend church?

Cropper: No, I went to a lot of concerts where church bands played. They’d have those revival meetings where they would play, and they’d have 10 or 15 church bands on a stage, and I’d just sit there with my mouth dropping open. I just couldn’t believe it, you know? And the radio—I heard a lot of those old Gospel records on the radio, and some of those things were just fabulous. And of course, I took some of that influence and put it into sessions at Stax. Absolutely. I’d be lying if I said different. And I would think, “Well, now if I change the lyrics on this—if I change this to a pop song or an R&B record from a Gospel one, is God gonna come down and shoot me or something, put me in jail? I don’t know!” And I just kept going.

Paste: The interesting thing is, when Elvis came back from the Army, he looked around at Beatlemania and the British Invasion, and instead of trying to compete, he doubled down on what he did best and made a great Gospel album, How Great Thou Art.

Cropper: Yeah. One of the best, ever. And Ray Charles did that, too he came to Nashville and cut all these old country songs.

Listen to “The Go-Getter Is Gone” from Steve Cropper’s latest release:

Paste: Given all your various formative influences over the years, I have to say, on the very opening track of your new Fire it Up album, “Bush Hog, Part1,” your guitar just starts talking. It sounds like an old neighborhood friend.

Cropper: Ha! Well, we had a lot of fun doing it. And that’s not the original title, but I went back and I’d periodically pull up this instrumental that I did that I thought was so good , and it was just one of those accidental things. I just was playing along to the bass, and we cut the track, and I didn’t even think it would ever come out. But there it is. And we split it into “Part 1” and “Part 2,” because it has to do with what record companies are forced to pay for the number of cuts on an album. I think you’re limited to 12 cuts, and if you put more than that, you have to pay extra. So when record companies would put out these double albums because the artist wanted to, if it doesn’t sell a lot, they’re gonna lose a lot of money. Because they’ve gotta pay all these writers and publishers anyway.

Paste: So there will not be a Target bonus-track edition of Fire it Up, then?

Cropper: I don’t know! But there are three finished tracks that are not on this album, and it was my co-producer Jon Tiven’s idea. He said to the record company, “What do you think about putting out maybe an EP? With two songs on one side, one on the other?” An extended play! So we don’t know what’s gonna happen with that—we have no idea. But we just wanted to give ’em the option—we can either save ’em for the next album, or get ’em to the market sooner, in the next few months. So we’ll see.

Paste: Where did you find this vocalist on the album?

Cropper: This guy, Roger C. Reale, he’s been around, and he’s an old buddy of Jon Tiven’s. And I said, “Well, we need to find a singer.” And he said, “I’ve got one!” So he had him sing a couple of things and he sent ’em to me, and I said, “Holy crap! Where’s this guy been all my life?” So we talked back and forth, and we ended up finishing the album together. And all those vocals on it were done through an iPhone—not in a studio with a microphone, but in his house in Rhode Island through an iPhone.

Paste: But I advanced you $10,000 for this recording! Where did you spend it?

Cropper: Ha! I gave it to the Penguin!

Paste: Link Wray never really sang because he had only one lung. But why haven’t you stepped up to the mic?

Cropper: Well, I have, but a lot of times I don’t take credit for it. I had two albums out on MCA, and that was back when I was learning to sing. And I thought they were terrible. And somebody had to remind me in an interview the other day—I said, “You know this is the first album that I’ve really had out since 1968.” And they said, “Well, what about those two records on MCA?” And I went, “Aw, shit—I forgot about those!” They were so bad to me that I had just blocked ’em from my mind—I didn’t even remember doing ’em. But the first one wasn’t bad—there was a song called “Playin’ My Thing,” and I thought that was a good song.

Paste: With all the modern recording technology that’s available, have you got your own computerized home studio now?

Cropper: Well, I should. But I have never had a home studio, for one reason only—I don’t bring my work home. And I don’t wake up in the middle of the night with an idea and call the musicians and get everybody in at three o’clock in the morning. Nope. I don’t do that. If we don’t get in the studio in today’s session, we’ll just get it tomorrow, or maybe the next day. So I can go home, get some rest, eat a good meal, go out and hang and have some fun. That’s just the way I am! But going out? Eating a good meal and having fun? Oh yeah, right—that was the good old days.