We’ve Got So Far to Come: Stevie Wonder’s Fulfillingness’ First Finale at 50

Five decades later, some of us are still learning about Stevie Wonder.

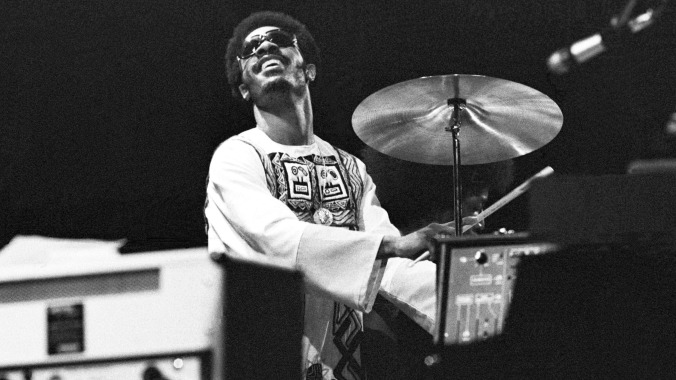

Photo by Ian Dickson/Redferns

By the time Stevie Wonder released Music of My Mind in 1972, he had already recorded 13 albums. Signed to Motown at age 11 in 1961, Stevie spent the first five years of his career as “Little Stevie Wonder” under the direction of Motown CEO Berry Gordy and songwriter-producer Clarence Paul, many of whose decisions regarding Stevie’s creative direction are laughable in hindsight. It’s hard to square an artist with one of the most undeniable legacies in modern music with the teenaged Stevie of the mid-60s, whose repertoire included Paul’s hokey arrangements of Bob Dylan hits and standards like “Teach Me Tonight” (the latter a decidedly unhinged choice for a 16-year-old to sing).

Despite Little Stevie’s general standing as a beloved child star, there wasn’t much to differentiate him from other novelty acts of the day. It wasn’t really until 1967 (after Motown almost dropped him) that Stevie Wonder the creative force began to take shape, but he wouldn’t be able to break out of his restrictive contract until he was 21.

In 1971, a month before his 21st birthday, Stevie released the album Where I’m Coming From, co-written with Syreeta Wright, his wife at the time, and fully self-produced. From today’s vantage point, it’s a bit unbalanced, and it seems somewhat overwrought—at least compared to the winking clavinet bounce of the Stevie that would soon come to be. But it’s also Stevie Wonder on a glittering precipice, experimenting with synthesizers for the first time, his preternatural gift for melody on full display.

It was Where I’m Coming From, not “My Cherie Amour” or “Signed, Sealed, Delivered (I’m Yours),” that launched him into the synth-bass haze of Music of My Mind, his first release back with Motown under a new, 120-page contract. Just over six months later came the funk-fueled Talking Book, and then the blazing Innervisions. In 1974, Fulfillingness’ First Finale arrived and, in 1976, Stevie’s storied run concluded with the titanic double-album Songs in the Key of Life.

It’s difficult to think of another artist whose discography is discussed in the same way as Stevie’s. There are, of course, other musicians with impressive runs of successive albums that not only dominated commercially, but are almost universally agreed upon critically—take OutKast 20 years ago, for example, or Beyoncé, who is on a streak of her own that shows no sign of ending soon. But you’d be hard pressed to name anyone else who did it in a mere four years, especially with a near-death experience smack dab in the middle of it.

On August 6, 1973, three days after the release of Innervisions, Stevie was in a car accident with his cousin while both men were on their way to a show. A logging truck slammed on the brakes in front of them, and allegedly, one of the logs crashed through the windshield and into Stevie’s forehead. Seriously injured, he was in a coma for four days. I say “allegedly” because there doesn’t seem to be a clear consensus about the details of the event, which has been recounted differently by Stevie’s mother, the truck driver, his bandmates in the cars behind him and the numerous media outlets that covered the incident.

The fourth record in the marathon-like run, Fulfillingness’ First Finale, was released on July 22nd, 1974, less than a year after the accident. Much like the accident itself, Stevie Wonder’s classic period is surrounded by a sense of mythos that is surprisingly opaque, given that Stevie is alive and well, and someone could presumably just ask him. But the question I’ve asked myself repeatedly since embarking upon what can only be described as an obsessive spiral of research is: Do we really want clarity anyway?

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-