The Masochistic Acrobatics of Taylor Swift

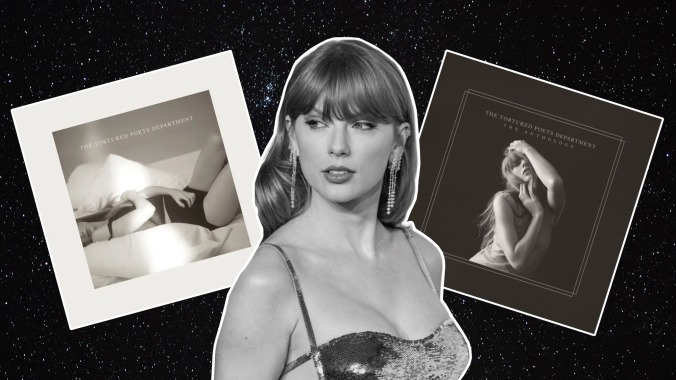

In the wake of The Tortured Poets Department's release, fans, haters, and ambivalent listeners alike are now reckoning with the pop star's new “greige” era.

Photo by Image Press Agency/NurPhoto/Shutterstock

I am not a skeptic nor an apologist. I understand Taylor Swift is omnipresent, like air or water. She is an element of the music landscape that some who write about the industry seem ashamed of despite her enormous influence. Every era of my life has been soundtracked by Taylor Swift. I can recall where I’ve been before every major drop. I pre-ordered Fearless after hearing “Teardrops On My Guitar” on Radio Disney and I put the poster up in my room of a decked out princess. When Speak Now came out it took me a while to get into it, but when high school ended I found myself driving around Indianapolis with the CD in my car crying to songs like “Dear John” and “Last Kiss” and their lush, evocative poetry. Red was instant, just like the color itself. I went to Nashville with my family when the album came out; I remember putting “Treacherous” as a Facebook status and getting bewildered comments.

All of that changed in college. I lost the privacy of my music taste. Suddenly “Shake It Off” and “Blank Space” were everywhere. Between lattes and Grey’s Anatomy reruns, everyone was listening to the princess of pop. Somehow she’d outplayed even Lady Gaga with her sheer relatability. She was no longer mine, but a phenomenon—or so I finally came to realize. Gone were the days of watching her YouTube diaries. I went to a stadium and watched her carefully calculated performance perfectly executed. She reminded me of Blair Waldorf in Gossip Girl, a girl who was trying so hard to execute every last step with precision. That, I would come to realize, was the same kind of girl I was—trying so hard and wanting it to look effortless. A few months later, I briefly dated someone who charmed me by saying they learned “Mine” on guitar. “You are the best thing that’s ever been mine,” I thought, as we waded in a lake in Bloomington, Indiana. Someone got it.

I got my first job after college around the time “Look What You Made Me Do” came out. The backlash was immediate. I said I liked the song and everyone else was confused. I liked Sade, Blondie, Mitski—how the hell could I like Taylor Swift? Wasn’t that what the music the Upper East Side kids we served cake and ice cream liked? The truth was: My feet were in both worlds, a desire for the delicious transgression of a repressed girlhood and the longing for cool, something I was always worried I was decidedly not. Still, I loved Reputation even after reading the damning New Yorker review. I listened to the album on planes and felt the slick sexiness of her new songs. Her cursing, even. “Only bought this dress so you could take it off,” I intoned as I made my way to the Met for a first date, hoping my chosen location would obscure the fact I was barely making enough to pay my rent.

Vindication was sweet. Lover inaugurated the girlboss’ comeback. She talked openly about Kanye West, snakes, her feuds and her new boyfriend. She had a new life. The hazy pink hues gave signs of renewed life. Every few years were a reset—maybe for all of us, too. Reputation was inspired by Game of Thrones, a take on violence and love. She released a documentary and talked about her fears over talking about politics publicly. Her father tried to shut her down. Couldn’t we relate? Miss Americana and the Heartbreak Prince?

All of this you know. There’s no way to avoid it. Laura Snapes of The Guardian has a dedicated newsletter. There is a Taylor Swift “beat.” I am feeding the beast now; the stakes have never been higher. Folklore and Evermore were both critically-acclaimed for their turn towards characters, lyrical songwriting and indie collaborations with the Dessner brothers and Bon Iver. They’re lush albums with cutting edges—“This is Me Trying,” “Mirrorball,” “Invisible String,” “Cowboy Like Me” and “Closure” offered some of her best musical moments. When those albums came out, she seemed far from over. Unlike artists like Madonna or Gaga, her reinventions were slight but effective. She’d keenly attuned to her image. “I’ll show you every version of yourself tonight,” she croons, like an Adult Contemporary artist.

Midnights, then, struggled under the weight of expectations. Further dogged by the many album re-recordings she’s done to earn back her masters (another highly publicized and discussed event). More like 1989 than any previous album, the bubbling electropop of songs like “Maroon” and “Lavender Haze” sounded almost like impersonations of Lorde or Lana Del Rey. Yet, paradoxically, she has never been more Taylor Swift ™. The Eras Tour movie was a hit, even if skeptics may have been even more wary of her omnipresence. (The Guardian noted the US leg of the tour was larger than the GDP of 35 countries.) She’s even collaborated with endless artists: Phoebe Bridgers, Hayley Williams, Ice Spice, Fall Out Boy, Lana Del Rey, Ed Sheeran, Bon Iver, Kendrick Lamar. Yet her ubiquity has caused issues. Niko Stratis has described the hate mail she received after her review of Midnights came out. Herein lies the problem—to declare oneself a fan one must align with the fandom, now known for its often vicious attacks on critics and writers, we must love things enough to take them apart.

She is a lightning rod for the Right, who see her as a cudgel of normality. Even if she wants to put space between herself and the “Sarahs and Hannahs in their Sunday Best,” she has struggled to not be crowned an Aryan princess. B. D. McClay has covered this beat extensively on Substack (and appeared on Know Your Enemy to talk about Taylor Swift Derangement Syndrome.) She gets under everyone’s skin. The Right decry her boyfriends as not fertile enough, the Left wants her to do more than ask people to vote—and somehow, she is sort of just down the middle. She’ll decry Marsha Blackburn but refuses to endorse Biden. Oddly, that second sin makes both the Left and Right happy. “The bigger reason that I find all this a bit pathetic is that Taylor is… normal. That’s her whole thing. Her brand is that she’s a sweet blond lady who loves her cats, her family, baking, and making music,” McClay wrote.

Taylor Swift is a woman who turns delicacy into a sparkly weapon. She’s coordinated enough good press the past few years to inspire a new wave of backlash over her participation in a new Miss Americana dream: dating a football player. Award shows are opportunities for new album announcements and chimera-like reinvention. Now, she’s a musical theater kid again: tortured, journaling bad poetry and speaking with a melodramatic flourish. Unlike the horrible, cheery kitsch of songs like “ME!,” she’s self-serious now. Her new album has not one but four bonus track versions only available through buying the full album on her online shop. Gone are the days she was compared to Joni Mitchell—she’s a Madonna without the humor; she wants to be graceful, a masochistic acrobat showing us her wounds. When she strikes gold, she can deliver pop polemics like “All Too Well,” but when she gets lost in the electro-ooze of a project like Midnights, she can sound just like every other Lana Del Rey wannabe. Too often Swift assimilates her competition through features rather than fully evolving. Still, we listen anyway, hopeful the American Dream holds something different.

And when she sounds different, we’re stunned. “Anytime now he’s gonna say it’s love / You never called it what it was,” she chants on the 10-minute version of “All Too Well”—perhaps when all is said and done her best diatribe, her most honed critique of patriarchy and emotional depth. Screaming along in the car is cathartic. She is for the girls driving in the suburbs high on rage over boys or men or painful friendships. She is a poet for the wounded. “So casually cruel in the name of being honest” understands the misogyny inherent in the everyday language of men. Even words like honesty become code words, bombs. Yet can’t women use knives too? That’s vigilante shit.

Swift is more comfortable singing about misogyny now. “The Man” was a big step, but developed into something more nuanced on Midnights. “1950s shit they want from me… the only kind of girl they see is a one night or a wife.” The problem is when a break-up’s horror stretches beyond the framework of misogyny to include the dire straits of class. Her new album has already struggled under the weight of Swiftian over-saturation. Pitchfork, Paste and The Washington Post have all penned pans.

The Tortured Poets Department is the vision of a high schooler—down to the track entitled “So High School” and her use of the word “greige” as an actual color. It’s high concept without depth—the illusion of sex without texture. A sprawling, light electro beat where one track flows into the next without much differentiation. Jack Antonoff never uses too much percussion, preferring instead for songs to meander—as evident on Lana Del Rey’s more recent output—and for his muses to sing lullabies of AI where poetry sounds like “vipers in empath’s clothing.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-