Music critics fall in love with certain adjectives (I should know; it happens all the time to me), and one of their favorites is “swampy.” It’s an irresistible adjective, for it sums up in one short word a sound that’s as real and as addictive as it is hard to pin down.

Tony Joe White, the grandmaster of “swampy” music, died on Wednesday of an apparent heart attack in Nashville at age 75. The songs that’s he’s best known for—”Polk Salad Annie” (a U.S. hit for him and a U.K. hit for Elvis Presley), “Rainy Night in Georgia” (a hit for Brook Benton), “Willie and Laura Mae Jones” (a hit for Dusty Springfield) and “Steamy Windows” (a hit for Tina Turner)—all had that thing, that combination of languid groove, Southern storytelling and Gulf Coast humidity best described as “swampy.”

It’s a word rooted in geography, in the floodplain along the Mississippi River south of Memphis and in the marshes and swamps along the Gulf Coast. These wetlands, where the ground is spongy underfoot and the air overhead pregnant with moisture, do not encourage sudden bursts of energy. They encourage deliberate, measured movements and a patience well suited for fishing and drinking, leisurely storytelling and unhurried sex. That’s what “swampy” music sounds like.

That was White’s music. He grew up in the northeast corner of Louisiana, across the Mississippi River from Yazoo City. He didn’t invent the genre, but he absorbed it from older bluesmen such as Houston’s Lightnin’ Hopkins, Baton Rouge’s Slim Harpo and Mississippi’s Jimmy Reed and translated it into baby-boomer songs for a baby-boomer audience. The spare, stinging guitar figures and just-behind-the-beat accents were still there, but the lyrics were actual narratives now rather than collected aphorisms.

“We lived on a little cotton farm down by the river in a place called Goodwill,” White told journalist Holly George-Warren in 2005. “My dad had forty acres of cotton and seven kids. They all played guitar and piano and sang all the time, but I wasn’t really into it till I was about 15. My brother brought home an album by Lightnin’ Hopkins, and I heard that old man play and, man, from then on I got my dad’s guitar and locked myself in the bedroom. The song I remember most was ‘Baby, Please Don’t Go’—just him and his guitar and a Coca-Cola box under his foot. It done something to me inside. My dad showed me a couple of chords and that was it.”

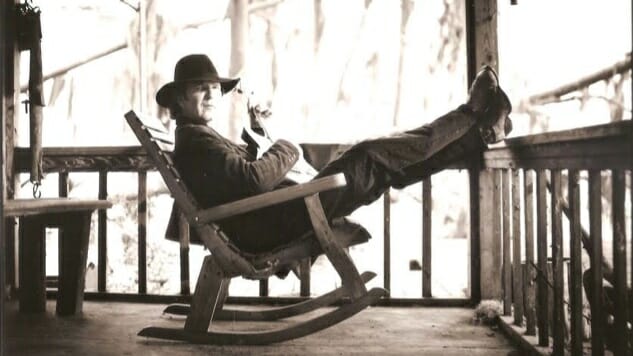

Watch Tony Joe White perform live at Paste Studio last month:

White heard Reed and taught himself the harmonica; he heard John Lee Hooker and taught himself that swamp boogie lick. Before long, he was playing house parties with his own Coke box underfoot, a guitar strapped across his shoulders, and a harmonica rack around his neck. That was all he needed to get people dancing.

The swamp sound is built around a seeming paradox: relaxed funk. In cooler and drier climates, dance music usually has a frantic urgency, but along the Gulf Coast and lower Mississippi music is slowed down so the listener still wants to dance but with the indolent sensuality of a sauna. You’re being urged to get up and move, but you’re being urged to not move too fast. It’s neither frenetic nor sedentary but a delicious limbo in between.

“I’ve seen them in nightclubs get down on their bellies like an alligator and move around,” White told George-Warren. “It’s primitive and it makes people want to have contact with someone. Swamp rock moves and sweats and steams.”

He spent his late teens and early 20s in Corpus Christi, where he started writing his own songs to fit this sound. He was there in 1967 when he heard Bobbie Gentry’s “Ode to Billie Joe” and thought, “I’ve been to that bridge; I’m going to write about something I really know about.” One thing he knew about was polk salad, a dish made by poor whites and poor blacks down South from pokeweed, a wild plant that tastes a bit like spinach and asparagus if you pick it early enough and boil it enough times.

A second thing he knew about was the kind of young Louisiana woman who could whip up a meal of cornbread and polk salad with no money to speak of and then dare you to eat one forkful less than all of it, if you know what I mean. A third thing White knew was the kind of repeating, hypnotic guitar riff that John Lee Hooker made a career off, a lick as percussive as it was melodic, that sounded like an alligator crawling from a bayou up on the bank or a young woman yanking pokeweed from the swamp.

White put it all together into a song called “Polk Salad Annie” that began with a spoken explanation for audiences unacquainted with the Southern swamp and worked the guitar figure into a feverish chorus that declared, “Polk Salad Annie, gator got your granny; everybody says it was a shame.” He wrote a mess of other songs almost as good and headed for Nashville at the end of 1967.

“A little guitar will keep going through my head,” White told journalist Chris Bourke in 1993, by way of explaining his songwriting process. “I’ll sit down with it and say, hey, ‘I’m here. Show me what you’ve got.’ And once they get started, I’ll put in hard hours with them. I’ll build a little campfire outside my house, get me an acoustic guitar and sit out there with a few beers at night and work with it. But until that happens, I don’t mess with it.”

In Nashville, he quickly signed as a writer with Combine Music and then as an artist with Monument Records. The 1968, Billy Swan-produced debut album, Black and White, stumbled out of the gate with four singles that flopped in the U.S. The fourth one, “Soul Francisco,” though, became a big hit in France and the fifth one, “Polk Salad Annie,” became a big hit in Texas. Slowly but surely the latter song rose to #8 on the Billboard charts, the only top-10 single White ever had in the U.S.

That was enough to make the music industry recognize what an original writer he was. White’s remarkably, subtle song about his black neighbors as a child, “Willie and Laura Mae Jones,” found a place on Dusty Springfield’s legendary Dusty in Memphis album. Brook Benton turned the gorgeous ballad “Rainy Night in Georgia” into a #1 R&B single and a #4 pop single in 1970. That same year Elvis Presley included “Polk Salad Annie” on his On Stage album, and it remained a staple of his live show until he died. Presley also recorded White’s “I’ve Got a Thing About You Baby” for the 1973 album, Good Times.

“Elvis’ producer called me,” White told Offbeat writer John Wirt earlier this year. “He said, ‘We’re flying a jet down to pick you and your wife up. We want you to come to Las Vegas and watch Elvis record ‘Polk Salad Annie’ for six nights, every night he does it on stage.’ Every night in Las Vegas was so wild. Elvis was putting out. He said, ‘You know, I feel like I wrote ‘Polk Salad Annie.’ I can sing it.’ I said, ‘That’s for sure.’ We went back to the dressing room after the show each night. He had an acoustic guitar back there. He’d say, ‘Break me out a blues lick, man. Show me two or three licks I can do.’ And I did him a John Lee or a Lightnin’ thing.”

White took to calling himself the Swamp Fox, and producer Jerry Wexler touted “swamp music” as “the emergent thing” in a 1969 manifesto for Billboard Magazine. It didn’t become as big a thing as he might have hoped, but it did influence a generation of singer/songwriter/guitarists. It soon became obvious that you didn’t have to actually grow up in a swamp to play the music. Outsiders such as California’s John Fogerty, Ontario’s Robbie Robertson, Oklahoma’s J.J. Cale and London’s Eric Clapton and Mark Knopfler all mastered the style.

Cale, Clapton and Knopfler all repaid their debt to White by guesting on his 2006 Uncovered album, joined by Waylon Jennings and Michael McDonald. Jessi Colter, Shelby Lynne, Emmylou Harris and Lucinda Williams paid similar homage on White’s 2004 album, Heroines. In 1989, White played guitar on Tina Turner’s Foreign Affairs album and wrote four of the songs, including the title track and the hit single “Steamy Windows.”

“You want to talk about heroes,” White told journalist Simon Sweetman last year, “it don’t get much better than writing a song and producing music for Tina Turner…. She’s one of the great singers of all time, she is rock’n’roll and blues and soul, so to have her singing so many of my songs and, ah, especially ‘Steamy Windows,’ yeah, that’s pretty special. Still.”

Kenny Chesney covered “Steamy Windows,” and Willie Nelson titled his 2017 album God’s Problem Child after a song that White co-wrote with Jamey Johnson. All these tributes raised White’s profile again, and he was able to put out a record every few years and to tour regularly—almost always with just himself and a drummer, and, believe me, that was more than enough.

His last album, Bad Mouthin’, released just a few weeks ago, is his own tribute to his blues influences: Hopkins (“Awful Dreams”), Reed (“Big Boss Man”) and Hooker (“Boom Boom”). But he never could quite recapture the songwriting powers of his peak moment, 1968 to 1972, when he released the five albums that introduced most of the songs he’s best remembered for today.

Fogerty’s Creedence Clearwater Revival hired White’s band as the opening act for a 1971 tour of Europe and America. White had a crackerjack band anchored by bassist Donald “Duck” Dunn of Booker T. & the MGs, and they battled Creedence for the swamp-music crown every night. A tape of one of those nights, later released as the album That on the Road Look “Live,” documents that showdown.

“Creedence tried to burn us down,” White wrote in the liner notes, “and we tried to burn them down, because they were going around ‘Swamp this and swamp that,’ and ol’ Duck … told them, ‘You know, Fogerty, there ain’t no alligators in Berkeley.’ From then on, it was war every night on stage.”

On the recording, White sings five songs alone with acoustic guitar and/or harmonica, one R&B ballad and six stomping, sinuous swamp-rockers. The album climaxes in a 10-minute version of “Polk Salad Annie” that’s all about excruciating tension and exhilarating release. It’s one of the greatest rock ’n’ roll live albums of all time.