His lips were a lifeless blue. Foam bubbled from his mouth. Having unknowingly shot up a large dose of fentanyl-laced heroin, James was overdosing hard, screaming towards death.

But being a seasoned addict, James pulled through.

“I carried myself through one of the hardest overdoses I’ve ever had,” says James, a recovering opioid addict in Salinas, California.

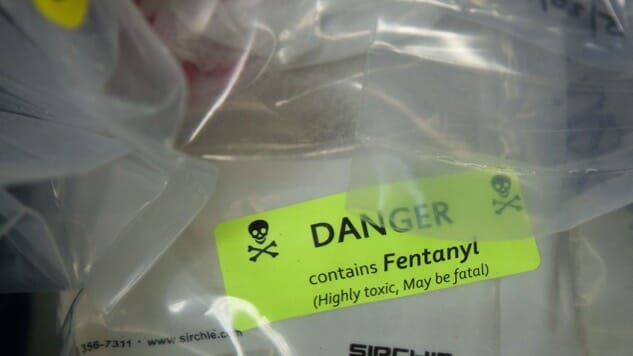

Most people aren’t so lucky, the waves of fentanyl-related deaths across the U.S. in 2016 are a grim testament to its lethality. While overdose deaths from painkillers decreased, heroin picked up the slack. The arrival of fentanyl in mass quantities is the third act to this ongoing American tragedy. In some areas and states, such as Long Island, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire, fentanyl now outpaces heroin as the leading cause of overdose deaths. And with President Trump antagonizing China—the chief fentanyl supplier —as well as remaining adamant about repealing Obamacare—which gives many opioid dependent people access to treatment—overdose deaths from fentanyl look to surge in 2017.

“It’s kind of like the perfect storm,” says Russell Baer, DEA spokesperson.

James’ path to fentanyl parallels that of many American opiate addicts. James began taking Oxycontins orally. He started shooting them soon after, his body having built up a tolerance to the dosage. But Oxycontins are expensive. It can be a $200-a-day habit for heavy users. It was only a matter of time before James, like millions of other opioid dependent Americans, turned to heroin; the black tar and powder heroin from Mexico is strong and much cheaper than Oxycontin.

Fentanyl was also a logical progression for organized crime. Not only could fentanyl be cut with heroin—extending traffickers’ heroin supply—but it could also be pressed into counterfeit painkillers disguised as Oxycontin—thus tapping into the prescription pill market at a time when supply was low.

“There are far more prescription pill users than heroin users,” says Dr. Joji Suzuki, a psychologist who works on opioid addiction at Harvard Medical School. “So people figured you could target the prescription pill user market by making counterfeit Oxycontin with fentanyl.”

Like James, many users believe they’re taking an Oxycontin or shooting heroin when in fact they’re getting a dose of fentanyl.

“A lot of my patients, when we test their urine, are shocked that there’s only fentanyl in their sample,” says Suzuki.

But it doesn’t take much to cause a wave of fentanyl-overdose deaths; a few grains of fentanyl can kill. Unevenly mixing heroin and fentanyl or putting a little too much in a batch of counterfeit pills can have grave consequences. The 72.5% increase in synthetic opioid deaths (9,580 in total) between 2014 and 2015, much of which was fentanyl-related, testifies to this trend.

But reliable numbers are hard to come by. Many states, such as New York and California, don’t have specific data related to fentanyl overdoses. And according to Dan Bigg, cofounder and director of the Chicago Recovery Alliance, the high variability in medical examiners makes it difficult to correctly determine the cause of death in all cases. Furthermore, the specific drug related to the overdose isn’t reported in 20% of the cases, according to Courtney Lenard, Health Communications Specialist at the Center for Disease Control (CDC). The number of fentanyl-related deaths is probably much higher than current numbers suggest.

“I don’t think we know the extent of the fentanyl distribution because we’re not comprehensively testing for fentanyl in all places,” says Suzuki. “Within the last year we started testing for fentanyl, but we can only test for regular fentanyl. There’s a large chunk of fentanyl out there that isn’t regular fentanyl.”

Most fentanyl emanates from China. The country’s vast chemical production industry churns out copious quantities of the substance, according Tun Nay Soe, regional coordinator for issues regarding drugs and precursors at the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) East Asian office. And through various loopholes in Chinese law, it’s legal for Chinese companies to export certain fentanyl compounds to countries where they’re prohibited.

Chinese authorities have been working conjointly with the DEA—who recently opened an office in Beijing—to classify and prohibit the production and export of certain fentanyl analogues. But laboratories in China, in a kind of underground chemical arms race, are rapidly outpacing the efforts of law enforcement both there and in the U.S.

“New fentanyl analogues are developed rapidly by slight alterations in the chemical structure and enter the market as soon as the previous ones are banned,” says Nay Soe.

The 300% increase in furanyl fentanyl – a fentanyl analogue – identifications in the U.S. in 2016 exemplifies this trend.

With an uninterrupted procession of packages and shipments surging into the U.S. from China, slowing the flow of fentanyl has been difficult, according to Baer. But fentanyl and its precursors aren’t just flowing into the U.S.; they’re also flowing into Canada and Mexico. And organized crime groups in both countries, like any business worth its salt, have all too happily stepped in to feed America’s raging opioid appetite.

Supply-side efforts may seem nothing less than Sisyphean in this light, but this fight has long been the cornerstone of U.S. drug policy.

“The policy has long been, we’re going to go after the supply and we’re going to go after the user,” says Dr. Robert Newman, who long headed the Chemical Dependency Institute of Beth Israel Medical Center in New York City. “We know that doesn’t work. If any policy has proven not to work it’s go after the supply and ignore the demand.”

Since its discovery in the 1960s, methadone has been the most effective treatment for opioid addiction. But given the strength of Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and the vociferousness of moral conservatives across the U.S., abstinence-based programs became the norm in treating addiction, according to Newman. But as Dr. Alice Gleghorn, the current Director of Alcohol, Drugs and Mental Health Services for Santa Barbara County Gleghorn, points out, abstinence-based programs are wholly ineffective in the treatment of opioid addiction.

It turns out, ironically, that medication-assisted treatment (MAT), such as methadone and buprenorphine, might be the most effective tool in reducing both the demand and supply of fentanyl over the long term.

“For people using heroin [or fentanyl] one dose of methadone is three doses of heroin [or fentanyl] that aren’t purchased in Chicago,” says Bigg, who has long worked to promote methadone treatment in Chicago. “In a sense, you’re taking over the drug use appetites from the illicit gangs and you put it in the hands of medical practitioners.”

One study showed that for every life lost, methadone maintenance programs saved two others.

But the implementation of a comprehensive demand-oriented treatment policy seems like a pipe dream; especially with a president who openly praises the repressive regime of Duterte and installs law and order men like Jeff Sessions as Attorney General. And as Trump pushes Chinese-American relations to the breaking point, he is, amazingly, scuttling supply-side measures as well.

U.S.-Chinese drug enforcement efforts have been perennially shaky, typified by ups and downs. Trump’s friendliness to Taiwan, economic wrangling with China, and planned “takeover” of the South China Sea might very well spell another down.

“Should the overall relationship deteriorate, China’s willingness to cooperate in secondary areas [such as law enforcement] will diminish,” says Dr. Robert Ross, an associate of the Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies at Harvard University.

Such a situation would make it that much harder to cut the flow of fentanyl into the U.S.

Demand-side efforts look similarly bleak. There are still an estimated 1.2 million people suffering from opioid use disorder that don’t receive treatment in the U.S. Though Congress passed the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act (CARA) in 2016, a lack of funding in the provision still leaves 420,000 people without access to treatment for financial reasons. Spatial inequalities also hamstring access to treatment for countless others. Most counties in the U.S. don’t offer any kind of maintenance programs and only 3% of primary care physicians were authorized to prescribe opioid antagonists, like buprenorphine.

With President Trump’s repealing of Obamacare imminent, what little treatment is available may become even more restrictive. If Congress doesn’t earmark significant funding to CARA, rescinding the Affordable Care Act (ACA) would deprive another 222,000 opioid addicts of insurance.

“When I lived in Rhode Island, when there wasn’t universal health care…people would be financially detoxed off methadone,” says Dr. Wakeman, Medical Director of Massachusetts General Hospital’s Substance Use Disorder Initiative. “I worry that if we move back to a system like that, we’re going to make evidence-based treatment even harder to get. It’s only going to fuel the crisis.”

In the meantime, fentanyl continues to pump into the hubs and hinterlands of America.

“There’s been an increase in all forms of fentanyl in 2016, powder, pills, and precursors,” says FBI Supervisory Special Agent Vincent Chambers. According to the National Forensic Laboratory Information System (NFLIS), fentanyl and fentanyl analogues have now been found in every state in the U.S.

And as long as medically assisted treatment eludes hundreds of thousands of opioid addicts across the U.S., overdose deaths from fentanyl will continue unremittingly onwards.

As James says: “Most people follow this to the grave.”