Trump’s Order to Stop Separating Families Is Useless and Likely Illegal

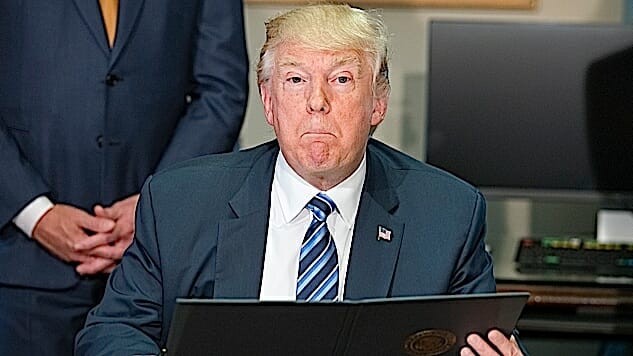

Photo courtesy of Getty

Yesterday, President Trump, under the duress of bipartisan outrage and less than a week after he said he couldn’t, signed an executive order that, per him, was “going to keep the families together” and solve the problem he created. The order was drafted by the Secretary of the Department of Homeland Security, Kirstjen Nielsen, who also said earlier she couldn’t do anything to change the policy.

But the name of the order — “Affording Congress an Opportunity to Address Family Separation” — suggests the order itself doesn’t completely solve the problem of family separation. It also suggests that Trump doesn’t want to sign the order, and doesn’t want to take credit for keeping families together.

Good, because the order doesn’t solve the problem, and Trump doesn’t deserve credit. Or: He’s an arsonist who showed up at the home he set on fire, blamed someone else, and, using a hose that sputters water, doesn’t put out the fire but soaks the ground around the burning house so other things don’t catch fire, and demands to be called a hero.

The house still burns.

Because like everything else about this story, the executive order is confusing and and contradictory, here’s an explainer.

Bottom line: It’s currently impossible and, weirdly, illegal.

Does the order reunite families we already split up?

This is the biggest and most immediate problem. The answer: Unclear, but unlikely.

First, there’s no language in the order that demands we reunite kids already taken from their parents. At first, officials actually said that these children would not be immediately reunited while their parents are in federal custody awaiting criminal proceedings. Kenneth Wolfe, spokesman for the Administration for Children and Families, a division of the Department of Health and Human Services, said that “There will not be a grandfathering of existing cases.” He then blamed the White House.

But his boss, senior director of communications Brian Marriott, said Wolfe “misspoke.” Marriott clarified that they actually have no idea whether they’ll try to reunite families already affected: “It is still very early, and we are awaiting further guidance on the matter.” That means it’s possible that the children already in detention might be united with other family members or guardians already living in the United States, and not necessarily the parent(s) they crossed with. This is our current policy for what we do with unaccompanied minors. Problem: Those minors crossed alone.

Another problem is sheer numbers: Over the last couple of months, the U.S. government has taken more than 2,300 children from their parents at the Mexico border. That’s an enormous amount of kids, but from a bureaucratic perspective it’s also an enormous amount of paperwork.

First, border authorities have track down the parents to reunite the families. A DHS official told reporters, “The biggest problem, as far as I can tell, is where the kids’ records don’t have information on the parents.” It’s unclear how DHS can work that out, especially with these numbers.

It’s also unclear how long it will take them. Gene Hamilton, speaking to reporters on behalf of Sessions, said something about a vague “implementation phase,” without detailing how long it might take.

Another hurdle: Because the policy filled children’s shelters at the border to capacity, DHS has been flying kids to shelters across the country. They’re scattered all over the country, and there’s literally no plan on how to reunite them, because the administration clearly planned on never reversing this policy.

Does the order stop us from separating families, PART I

When Trump signed the order he said, “I didn’t like the sight or the feeling of families being separated.” But will it stop that?

The correct question, though, is can it stop the policy.

Here’s the actual language that addresses the main problem of separation:

a) The Secretary of Homeland Security (Secretary), shall, to the extent permitted by law and subject to the availability of appropriations, maintain custody of alien families during the pendency of any criminal improper entry or immigration proceedings involving their members.

This means that instead of breaking families apart, we’ll now detain them together. Sounds like it solves the problem, but it’s more complicated. The language in the bill leaves open the possibility that, should the DOJ be able to defend it in court, kids can now be detained indefinitely with their parents in DHS detention centers. (Not shelters.) In other words: Family jail time.

But it’s not clear whether this is defensible in court. If not, this gives Trump two choices: Release families after 20 days, or release children after 20 days and hold their parents.

In other words, back to breaking up families, except instead of immediately, it’s after 20 days.

And if Trump can’t process all parents within 20 days of arrest, a monumental task, he’s actually breaking the law. Because…

Does the order stop us from separating families, PART II: It might be illegal.

The administration has consistently said that it was forced to separate families because of a “Democrat law,” which is actually a 1997 Supreme Court decision known as the Flores Settlement. That decision, clearly not a Democrat law, limited the time the government could keep unaccompanied minors in detention centers, and few years later another federal court ruled that the detainment limit can’t be longer than 20 days.

Flores told border authorities to transfer all unaccompanied minors to “the least restrictive” setting possible. Today that means taking them out of the detention centers (cages) and transferring custody from DHS to the Department of Health and Human Services, which places them in non-profit shelters where they wait to be reunited with parents, family, or guardians here in the U.S. After six months, these kids can be adopted.

But the law doesn’t require Trump to separate families. That’s the result of a discretionary policy Sessions enacted this April.

That new “zero-tolerance” policy essentially created a new pool of “unaccompanied” minors, because it criminally prosecuted their parents for crossing unlawfully, a federal misdemeanor. This the most extreme extent of the law, like throwing you in jail for months and taking your kids away for reckless driving, and no president took it this far before. We can’t put kids in prison with their parents, so because of existing laws we had to separate them at the border.

First thing: The order doesn’t eliminate the “zero-tolerance” policy that criminally prosecutes parents. “It continues to be a zero tolerance,” Mr. Trump said. “We have zero tolerance for people that enter our country illegally.” This means Trump’s order to keep families together, once technically legal, is now weirdly illegal: You can’t criminally prosecute parents while detaining kids with them in jail, and per Flores, you can’t detain families together for longer than 20 days without releasing them.

The order tries to get around Flores by ordering Sessions to fix everything. Here’s that language:

The Attorney General shall promptly file a request with the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California to modify the Settlement Agreement in Flores v. Sessions, CV 85-4544 (“Flores settlement”), in a manner that would permit the Secretary, under present resource constraints, to detain alien families together throughout the pendency of criminal proceedings for improper entry or any removal or other immigration proceedings….

The Attorney General shall, to the extent practicable, prioritize the adjudication of cases involving detained families.

So first problem: Sessions must fix Flores so Trump can keep families together, thereby detaining kids for longer than 20 days. Until that happens, what the order demands contradicts Flores.

Second: To address the above problem, the order says Sessions must now prioritize the criminal prosecution of family cases. It’s unclear whether that’s physically possible, given the current backlog. Once a family hits 21 days, expect a major lawsuit.

Bottom line: The order might be impossible. It’s unclear how long it will take for Sessions to get a court to change this, or even if he’ll be able to. A federal judge could reject the order as violating the 20 days rule. Bad news: That will probably happen. The courts have already ruled against it.

Also, a federal court ruled in 2015 that it’s unconstitutional to detain women and children as a deterrent to future immigration. Several members of the administration are on record calling this a deterrent, and Sessions’ 2017 order that begat this one actually says “deterrent.”

Does the order stop us from separating families, PART III

The order has specific language that doesn’t ensure families will be kept together. It says authorities will detain families together where legally appropriate and, more troubling, “subject to the availability of appropriations,” i.e., if there are available centers and funding.

There is in fact a reason for the “where appropriate” language. Some kids are brought into the country by parents who pose a criminal threat, and who might be trafficking them. We clearly shouldn’t keep them together. But that language also provides room for discretion. What’s appropriate? What’s a criminal threat? Unclear.

As for available resources, shelters and detention centers will soon all be at capacity, if they aren’t already. However, DHS can’t use the shelters for minors to house the families, which is the responsibility of HHS. Instead, DHS has to keep families in one of the three existing family detention centers: Two in Texas and one in, weirdly enough, Pennsylvania. Reports say the Texas facilities can hold a total of a little more than 3,000 people, and the Pennsylvania facility can hold only 96. The largest facility is nearly at capacity — currently about 2,000 people, according to ICE — and the others are over half capacity.

The administration acknowledges this in the order, however. What’s the fix?

Have the military build shelters. Nielsen passed responsibility from herself to the Department of Defense. No joke:

The Secretary of Defense shall take all legally available measures to provide to the Secretary, upon request, any existing facilities available for the housing and care of alien families, and shall construct such facilities if necessary and consistent with law. The Secretary, to the extent permitted by law, shall be responsible for reimbursement for the use of these facilities.

“Secretary” in this sense references the Secretary of Homeland Security, not the Secretary of Defense. So payment means another bureaucratic hurdle.

The end has no end

When asked for comment, the Department of Homeland Security did not immediately respond about how it plans to carry out the executive order. It can’t be more obvious, or repulsive, that Trump’s executive order, for reasons both substantive and superficial, was nothing more than a photo op. The administration created its own Catch 22, and now it’s realized it can’t wiggle out of it. There’s no solution. Expect a lawsuit within the next 20 days, if not immediately.

However, when that lawsuit does come up, it will in an inverted, doublethink way prove Trump right: He couldn’t do anything practical about his policy. Trump, however, will say he couldn’t do anything about the law, and that Democrats are the ones setting this whole thing up. When that happens, remember the facts: The law doesn’t require Trump to enforce his impossible and likely illegal zero-tolerance policy. It’s his cross to bear, and it will drag him down. No way he reaches the hilltop. He’s got bone spurs.