It Doesn’t Matter Who Democrats Nominate If They Don’t Win the Senate

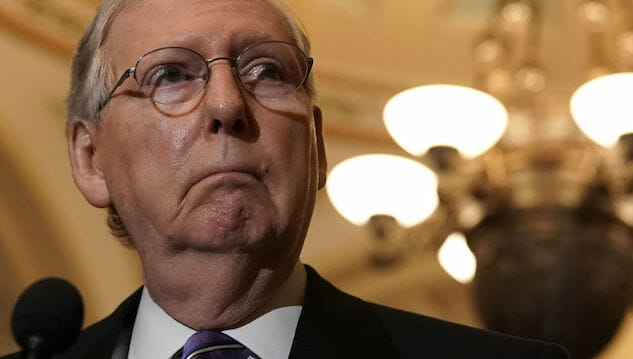

Photo courtesy of Getty

This will be a short column about a specific but obvious point going largely unnoticed in our conversations about the 2020 Democratic primaries: If Democrats don’t take the Senate in 2020, it doesn’t matter who they elect, or what their policy proposals and progressive credentials are. A GOP Senate will either block any progressive legislative agenda or water it down to the point it becomes meaningless and doomed to fail in the long term. In a sense, the intra-party debates we’re seeing today are not only unnecessarily vicious, they also put the cart before the horse: Winning the Senate—and holding the House—should be the top priority.

The fact that we’re not talking about this is shortsighted and self-defeating, but given we’ve combined our celebrity “main event” brand of political discourse—which is really nothing new—with our gradual acclimation to the market saturation of an authoritarian executive branch, it’s also understandable. We perceive, rightly or wrongly, that the presidency matters more than ever. In some sense this is accurate, because over the last two years Donald Trump has basically put on a clinic for this topic. At the same time, however, we’ve lost the lessons Mitch McConnell taught us during the Obama presidency: Our system is so at odds with itself that without total control of Congress, any Democratic president’s legislative agenda will fail.

This is frustrating. Today we have in many regards a dream scenario for vaulting progressive policies to the front of national politics: An intellectual vacuum in the Republican executive branch; a Republican legislative branch obsequious and extreme to the point of total dysfunction; and, thanks in no small part to these failings, a general population more open than ever to progressive solutions to the many urgent problems we need our government to resolve. To that last point, for instance, recent polls have reliably shown that seventy percent of Americans—not Democrats; Americans—support universal healthcare.

But also note that about that same number—around 65% of Americans—were in favor of a single-payer system in 2009. For a more acute example, an even larger number of Americans—between 82% and 90%—supported universal background checks for gun sales during President Obama’s last term. McConnell, however, led an infamously and probably unprecedented obstructionist movement that all but neutered Democratic action for the last six years of Obama’s presidency. Republicans then swept the 2016 election.

In other words, public will is one thing; political will another. Our politicians, especially in these hyper-partisan times, won’t necessarily reflect our will or advocate policies that even an overwhelming majority of Americans support. One reason is that it’s much easier, rhetorically, to talk someone out of doing something new. Alternatives abound, and the GOP has become frighteningly adept at appealing to conservative fears about risk and opportunity costs. In other words, not all people who support certain policies when polled will commit all-or-nothing to those policies. Regrettably, relatively few of them will. This means Democrats need to secure not just public support for progressive policies, we also need to secure the legislative mechanisms that are the only way those policies become reality. That is, they have to win the Senate.

Imagine, for instance, a Bernie Sanders presidency. Over the course of these next two years, he’s shaped the Democratic party to fit his vision, and on January 21, 2021, he comes out swinging with progressive legislation ready to go: Medicare for All; Green New Deal; assault weapons ban; tuition-free college; voting rights expansion; tax and wealth reform; hell, even the groundwork for UBI. Rad, right?

Now imagine a GOP Senate passing any of it.

In real terms, it doesn’t matter who Democrats put at the top of the ticket. No one will be able to override the checks and balances provided the Senate in the Constitution.

The nuclear option

One alternative, of course, is extending the authoritarian rails Trump has laid. For instance, when Trump failed to repeal Obamacare (despite complete control of Congress) he turned to executive order to choke it out. When he failed to build the wall (despite complete control of Congress) he declared a national emergency. Examples abound. And though I would argue climate change is an existential threat that would, beyond doubt, justify a national emergency (irrespective of however far Trump’s declaration lowered the bar for that definition), I’m not so sure whether we can apply that same calculation to some of the other serious crises we face, such as healthcare or gun control. Same goes for the Supreme Court nuclear arms race that led from removing the filibuster to obstructing Merrick Garland to appointing unnecessarily a justice who in all likelihood has a history of serial sexual, gambling, and alcohol abuse. Should a Democratic government pack the court? (Even if you argue they should, that still presumes Democrats win the Senate.)

That’s all to say that if Democrats lose the House or Senate in 2020, we can’t in good faith support an agenda enacted entirely by one person. That would affirm and accelerate a national trend that’s careening, subtly or not, towards authoritarian rule.

Consider that the first people to sound the alarm about Trump’s national emergency weren’t Democrats, but Republicans who feared Trump would open the door for a Democratic president to circumvent Congress by declaring emergencies for climate change and gun control. Democrats, obviously, welcomed this idea, but until then, I’d never heard—I don’t think—any serious Democratic politician make a serious argument that a president should declare climate change a national emergency. Trump, in that one act, re-framed the way Democrats see presidential power and democracy generally.

True, Americans have always seen presidents as more powerful than they really are, and Trump isn’t, by any stretch, the first president to extend or abuse his executive power. But until this moment the public has always pushed back against such overreach, from Obama’s signature drone strikes and immigration executive orders to Bush’s torture and surveillance programs, all the way back to the Gulf of Tonkin, which contributed to the 1976 National Emergencies Act designed to curb this executive abuse in the first place. Trump, however, has done everything in and outside his power to expand presidential authority, and if Democrats embrace this strategy, any future American governments—even progressive ones—will crack and crumble under the pressure of national partisan backlash. We must get serious about correcting this trend, and that means we must get serious about the Senate.

But can Democrats win the Senate?

We elect Senators every six years, and those elections are staggered. This means that unlike with the House (every two years) each election year for the Senate has a slightly different map. In short, 2020 looks better for the Dems than 2018 did, where they faced a notoriously difficult election map and ended up losing two seats.

In 2020, Democrats must capture four currently Republican-held seats to regain control. (Three if they win the presidency, because the vice president casts tie-breaking votes in the Senate.) The map looks promising. Of the 34 seats that will be on the ballot, Republicans currently hold 22. However, because most of those GOP seats are in solidly Republican states, Democrats will have to do a lot of legwork. Here are the best bets, per Nate Silver’s 538 blog.

The best odds are with two Republican Senators from blue states: Cory Gardner (Colorado), and Susan Collins (Maine). Gardner has a 39% approval rating. Though Collins has an approval rating of 53%, 538 notes that an Emerson poll taken after the Kavanaugh confirmation found that 47% of likely voters were less likely to vote for her as a result of her choice to confirm him.

Then we have Thom Tillis (North Carolina) and Joni Ernst (Iowa). Arizona is also in play. Though 538 notes that Arizona is “nine points more Republican-leaning than the nation as a whole (and 4 points more Republican-leaning than Iowa or North Carolina),” Democrats just won a Senate seat there by about two points.

Democrats will also have to retain their own seats on the ballot, which includes two openings in red states. One of them, troublingly, is Doug Jones’s seat in Alabama.

And though 538 doesn’t go there, I’d put John Cornyn’s Texas seat on this list. Though the state (where I live) leans Republican by about 17 points, Beto O’Rourke showed us last November that, depending on the nominee, the state is very much in play for 2020. To that end, considering the argument I’ve been making, it might have been better in the big picture for Beto to run for that seat instead of ruling it out early in favor of considering a shot at the presidency.

But take heart: The public will is there. Democrats just need to tap into it. They can’t afford to put all our focus—or even the majority of it—on the marquee event of the presidential race, and they certainly shouldn’t encourage toxic intra-party bickering about progressive purity at the top of the ticket. The much bigger concern of an obstructionist Senate obviates even the most pristine progressive credentials. If they don’t refocus, they might condemn themselves to four more years that look exactly like the last nine years—or worse—no matter who gets elected.