Online Project Segregation By Design Highlights The Historic Racism of Urban Renewal and Its Continued Influence

Images via Segregation By Design/HOLC

For NYC-based architect Adam Paul Susaneck, urban renewal has always been a particularly nefarious example of double speak.

In America, the term refers to the mid-20th century policy in America to clean out “blighted areas” in major cities, making way for upper-class housing and automobile-based transportation projects. Meant to solve several problems in post-war urban life, including overcrowding and dipping land values, the program enabled cities to seize and clear entire neighborhoods. By the late 1950s, cities were displacing tens of thousands of families each year, with families of color displaced at rates far higher than their share of the population. In their place, highways, large scale infrastructure and high-rise apartment buildings rose up, all generating five to ten times the tax revenue than the “slums” they replaced.

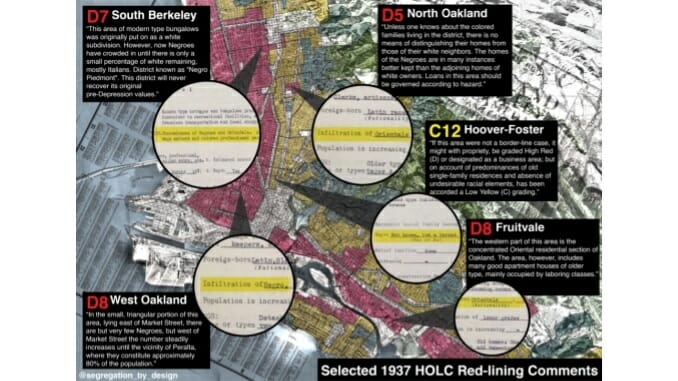

Unless you’re an architecture student, historian or generally curious about how cities were planned in America, there’s a good chance you’ve never heard about urban renewal or redlining. To that end, Segregation by Design – Susaneck’s self-funded project that uses historic aerial photography to document the destruction of communities of color in roughly 180 downtowns due to redlining, urban renewal, and freeway construction – is built on the mission of showcasing that history in hopes it can serve as a stark lesson. Even though the policies have changed, their legacy is still alive and well. Just this week, Houston officials went ahead with plans to demolish apartments to widen the I-45 through the city.

The aim, Susaneck said, is to amplify the voices of those who lived through it using the network the project has developed through its social media presence, mostly on Instagram, which has approximately 68,000 followers. In January of 2021, Susaneck posted his first missive on the site alongside maps of Rochester, NY overlaying “redlining” maps with freeway routes before and after construction. Since then Susaneck has covered major cities like Atlanta, Washington, DC, Boston, Providence, Houston, Oakland and Philadelphia.

Susaneck started the project mid-pandemic in 2021 after being inspired by Richard Rothstein’s book The Color of Law. In Rothstein’s award-winning book, the former Fellow at the Thurgood Marshall Institute of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund documents the evidence that governments not only ignored discriminatory practices in the residential sphere but promoted them. While Susaneck learned a lot from the book, he thought the lack of pictures was a missed opportunity.

“As an architect, I’m visually minded and what he’s describing was so visual, I just thought there could be a lot of value in providing that context and those images,” Susaneck told Paste. “I thought the skills I gained in school could be useful and the history was something I had been interested in for a long time.”

A fan of public transportation and more specifically trains from youth, Susaneck said he was also spurred to find out more as he found out that entire mass transit systems (see Houston) had been dismantled in favor of cheap housing and extended highways. Sharing the stories of forgotten neighborhoods, Susaneck said utilizing social media seemed like a natural way to disseminate the information while breaking it down into bite-sized posts. Susaneck said he was also inspired by a particular anecdote from The Sum of Us by Heather McGhee. In the book, McGhee describes “Drained Pool Politics’’ to illustrate one effect of urban renewal.

“In the 1930s during the New Deal, the federal government financed the building of grand, beaux-arts public swimming pools in cities across the nation. These pools were officially whites-only. Two decades later, when the Supreme Court ordered municipalities to racially integrate these pools, to avoid doing so many cities drained them and demolished them. Subsequently, there was a boom in the construction of backyard swimming pools in the single-family homes of racially-restricted suburbs across the nation.”