“Beware of Colombians with knives,” a friend in Atlanta warned me. “They can cut out your heart and hold it up for you to see while it’s still beating.”

This friend, like many in the months before I moved, meant his advice in the best possible way. I carried a litany of tender warnings when I stepped out of the plane in Bogotá last January. “Don’t drink the water.” “Never take a taxi on the street.”

Beware of Colombians with knives.

Little did I dream that a year later I would pay a Colombian to cut me. My surgeon repaired an injured cubital nerve, a thing in the elbow that tingles when you bump it the wrong way. The funny bone, it turns out, is no laughing matter.

I lifted a bag just the wrong way. Somewhere under New York City, hurriedly passing through a subway turnstile on an international trip, I hoisted a carry-on behind my back. Imagine a classic Frank Sinatra pose, the singer’s jacket thrown over one shoulder. That was me—only with my jacket in a bag with 30 pounds of other clothing and books. (Always books.)

Foolishly hoisting a bag that way irritated my cubital nerve. In return, my nerevs spent the next two months irritating me, a devilish vengeance that eventually woke me four or five times a night with pain and that prevented me from doing many things that required my right arm. I lost feeling in the pinkie and ring fingers of my right hand.

Writers need the right pinkie and ring finger. Without feeling in those two digits, they can’t be sure if they hit the ‘p’ or hyphen keys. (Try typing poo-poo without ‘p’ or ‘-’ … and oooo you’ll see exactly what I mean.)

Male and invincible and all, I refused for too long to go to a doctor. It was probably a mistake, but in its 61 years, my body has nearly always repaired itself. It’s been a good friend that way.

I did run into an inguinal hernia once that didn’t self-heal, and a doctor had to patch that up. All my friends and all the literature referred to that procedure as ‘minor surgery.’

I am here to tell you that one old cliché is absolutely true: When it’s your own, no surgery is minor.

After examining my injured arm, a Colombian surgeon told me that an out-patient procedure on my nerve to relieve pain and restore feeling would be … wait for it now … minor surgery, too.

I nearly ran out of his office when I heard those words.

Reader, you may be reaching the point in this travel essay where you’re wondering what an injured elbow has to do with travel to exciting and colorful far places. Okay, here’s the punch line:

Let’s say you’re a gringo in a strange land, a novice in the language and the lore … not to mention the medical standards and practices.

What happens if you need a small repair?

My story will likely be different from yours. I had the foresight to fall in love with a beautiful and good-hearted Colombian ophthalmologist, a skilled surgeon who specializes in restoring eyesight to the blind … or virtually blind. Dra. Castro removes cataracts and reshapes lenses so that people who can’t count fingers in front of their faces leave her care admiring every leaf on every tree and sailing through dark nights like bats.

Adela knows her medical community. Colombia happens to be blessed with a high standard of care, and not judged just by Latin American standards. A physician in Bogotá (Spanish ophthalmologist Jose Barraquer) invented Lasik surgery, for example, and the country gets a fair share of medical tourism—foreigners who fly in for a procedure at good prices and with excellent care, who then convalesce as they tour this fantastically beautiful part of the world.

I liked and trusted my surgeon, but I faced a decision. My insurance covers procedures in the United States, not Colombia. I had two options: I could fly back to the U.S., get in line to see a doctor, wait on an operation, pay out-of-pocket fees, recover for the week or so until the post-op exam, then fly home to Colombia again. Estimated cost? Two thousand dollars, or maybe $3,000, depending on how much fried chicken I ate. Or, my doctor in Bogotá could do the job for 2,600,000 pesos cash … the equivalent of just under $900 U.S. I could stroll to the clinic, have the surgery, and walk back to my apartment two hours later.

I have a trusting nature. I generally believe the best of people. Surgery here in my newly adopted country seemed to be a no-brainer.

This story has a happy ending … I hope.

I went under early on the morning of December 21, the winter solstice. In years past, I ritually climbed to the top of Stone Mountain on this shortest day of the year to watch the setting sun burn Atlanta yet again.

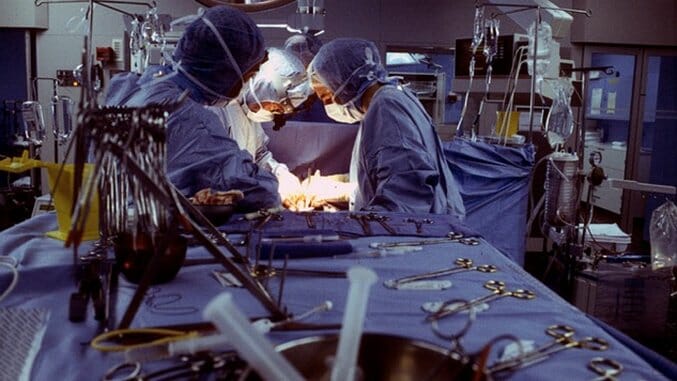

This year, I climbed onto a steel table with a blazing surgical light overhead. The doctor and his team were seriously professional. Only the anesthesiologist made small talk, telling some joke in Spanish as I counted backward from diez.

Two hours after the 20-minute surgery, I ambled with Adela a mile up Calle 19, a busy divided thoroughfare with broad brick sidewalks, bike lanes, shops and cafes. Salsa poured out the windows of passing cars. A c_affe con leche_ tasted delicious and brought me back to life. I held the cup left-handed, my right in a sling for a while. An old Civil War tune, “When Johnny Comes Marching Home,” jauntily played in my head.

It’s been a month now, give or take. The pain in the elbow passed, then came back, then faded. Then came back. I foolishly aggravate the nerve, I think, lifting things I shouldn’t, trying to be normal again. Trying to be a man.

I still have no sensation in my two fingers. My keyboard skills still suck, but I also can’t yet play guitar … or easily grasp objects I drop … or feel the warmth of Adela’s skin. My pinkie and ring fingers tingle exactly the way a foot does when it ‘goes to sleep.’ At a touch, I feel needles and pins under the skin.

The doctor tells me all is well, not to worry, nerves take an extra-long time to heal. He says the cubital nerve regenerates feeling at a rate of one millimeter per day. How many millimeters lie between my elbow and fingertips?

So, good reader, now you know a gringo surgery story. Against the advice of my friends in the good old USA, I made a choice to voluntarily lie down for a knife-wielding Colombian.

Time will tell if I should have run for my life.

Photo: dominique cappronnier, CC-BY

Charles McNair is Paste’s Books Editor emeritus. He served the magazine as writer, critic and editor from 2005-2015.