Kenya Barris’ #blackAF Is Art Imitating Art Imitating Life

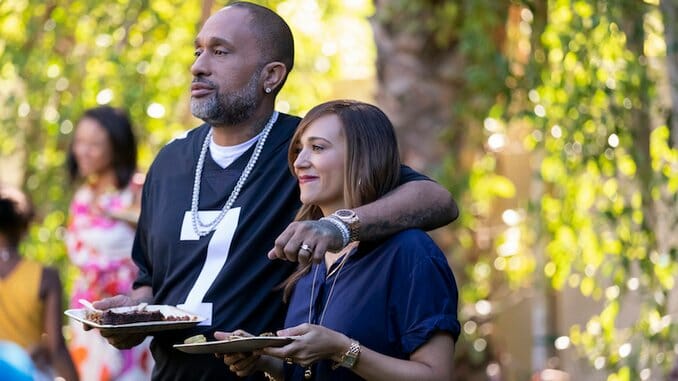

Photo Courtesy of Netflix

If you’re at all familiar with ABC’s black-ish, then watching Netflix’s #blackAF might feel like a surreal experience to you. Not just because it’s created by and starring Kenya Barris, creator and former showrunner of ABC’s black-ish, but because it’s pretty apparent throughout the eight-episode first season that this new series is essentially Barris’ undistilled, unapologetic, unperturbed by network television notes and interference version of black-ish. In fact, it’s hard not to think that this is the show Barris wanted to make all along but couldn’t under the umbrella of his Disney overlords.

Netflix describes the series as “a total reboot of the family sitcom that just so happens to be based on [Barris’] real life approach to parenting.” That’s exactly what black-ish was supposed to be, but this synopsis also comes across like a pointed reboot of that reboot of the family sitcom… which was also inspired by Barris’ real-life approach to parenting. (Tracee Ellis Ross’ character Rainbow was even based on Barris’ then-wife—name, profession, everything.) Only, in #blackAF, instead of Anthony Anderson’s Dre Johnson, it’s Kenya Barris’ Kenya Barris. This is Barris’ first acting gig—it shows, despite him being serviceable as himself—a choice admittedly inspired by Larry David’s work on Curb Your Enthusiasm. Rashida Jones—who appeared on black-ish as Rainbow’s Real Housewives sister, Santamonica—stars as Joya, Barris’ “lawyer” (she’s on an extended break) wife and mother of his six children, who is either a “boss bitch” or an aspiring Real Housewives cast member, depending on the scene. (Jones, easily the onscreen MVP of #blackAF, also executive produces and directs on the series.)

But Barris doesn’t just star as a very meta version of himself in #blackAF: He works predominantly on a set that’s been described as a “nearly exact replica” of his own real-life family home in Encino, CA. And if you’ve ever seen a black-ish scene with Dre at his place of employment, Stevens & Lido, then you’ll get a very distinct sense of deja vu once #blackAF gets to its writers’ room scenes with Barris. Both shows even share actor Nelson Franklin as part of these office debate scenes. Only, instead of Deon Cole in the office as wildcard Charlie, it has Bumper Robinson in the office as wildcard Broadway, with Angela Kinsey filling the role as the one white woman on the team, which Catherine Reitman (who guest stars in an episode of #blackAF) fills on black-ish. #blackAF also has producer/writer Jonathan Groff step out from behind the scenes, as former black-ish showrunner and Barris’ real-life collaborator, to in front of the camera as a writer character on in-show Barris’ staff.

Where #blackAF somewhat diverts from Barris’ original reboot of the family sitcom is its framing device. #blackAF is presented in documentary format, as part of the NYU film school application from Drea (Iman Benson), the second oldest of the Barris’ six children. (Rounding out the rest of the cast of Barris children, from oldest to youngest, are: Genneya Walton as Chloe, Scarlet Spencer as Izzy, Justin Claiborne as Pops, Ravi Cabot-Conyers as Cam, and Richard Gardenhire Jr. as toddler Brooklyn.) Unlike in black-ish, this allows for an in-story explanation for all the voiceover and black history lessons present.

In the pilot (“because of slavery,” which is the jumping off point for every episode title), Drea explains how her dad hired a full documentary film crew to work for her, claimed she would’ve been fine just filming on her cellphone—because, in her words, she’s “not an asshole.” The rest of the episode and season, however, suggest that she is an asshole, though. Because while Drea is introduced as the level-headed, morally-superior member of the Harris clan—supposedly too good for her family’s shenanigans and shallowness—she comes across as the biggest hypocrite, openly benefiting greatly from the privilege afforded to her by her parents (with the entire series’ premise), while complaining the entire time. The series makes the character intentionally smug, and the confessional moments when her parents verbally take her down a peg or two for that are great to see, but Drea is still the narrator of and gateway into the series. Yet, her relatability is pretty much shattered immediately because of the aforementioned hypocrisy. Which is, unfortunately, a disservice to Benson, who is good in the role and provides plenty of Jim Halpert-approved reaction shots.

Originally titled Black Excellence, #blackAF even manages to follow black-ish’s lead in terms of censoring titles that aren’t exactly good either way. (Neither show has a good title—and in the case of #blackAF, neither its current nor original title capture the spirit of what the show is—but sometimes you do want to go ahead and call them “black shit” and “black AS FUCK.”) As a show ultimately about a super-wealthy black family flaunting that wealth, now is an especially strange time to watch #blackAF, when people are struggling even more to make ends meet. And it’s not just because of the characters’ expenses when it comes to cars, meals, clothes (so many designer labels in the wardrobe), childcare—the Barris “real-life approach to parenting” apparently relies a lot on “the help” doing the parenting—but because the series looks and clearly is just as obscenely expensive as everything these characters pay for on it. The look of #blackAF is sleek, with director Ken Kwapis providing a very music video, Hype Williams’-esque style for the series, on top of the whole mockumentary thing. Take into account all the very specific needle drops for songs, clips from classic movies peppered in, and even a side-by-side, shot-for-shot remake of a scene from a Hughes brothers film in one episode, and it all reminds you just how wealthy Netflix is and how much wealthier the Netflix deal made Barris.

(Barris’ Netflix deal was for $100 million, so on the one hand, with that kind of money, it’s hard to criticize him for simply doing whatever he wanted to do with such riches and the creative freedom that Netflix allows. That’s technically all on Netflix and its model.)

Other than black-ish on a content level, the best modern comparison for #blackAF would have to come from the 2002-2003 one-season FOX series, Fastlane. Fastlane gained notoriety in its short time on TV for its obviously expensive budget and co-creator McG’s hyper-stylization. That’s truly the case for #blackAF as well, and while the series begins with a lot of discussion about black expectations and perceptions when it comes to wealth and the flaunting or presentation of that wealth, the distractingly expensive look and feel of #blackAF kind of undercuts Barris and the series’ actual message (that is, of course, all tied back to slavery, Barris’ self-proclaimed “North Star” in the series). For example, there’s definitely a message in the #blackAF episode that plays both Kanye West’s “Runaway” and “Blood on the Leaves”… but it’s hard to think about that or anything else that happened when you remember that there’s an episode that plays both Kanye West’s “Runaway” and “Blood on the Leaves.” There’s certainly style that comes with the series, but the substance is all muddled by the fact that Barris already got to many of the topics presented in these eight episodes on black-ish—only without the ability to curse freely.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-