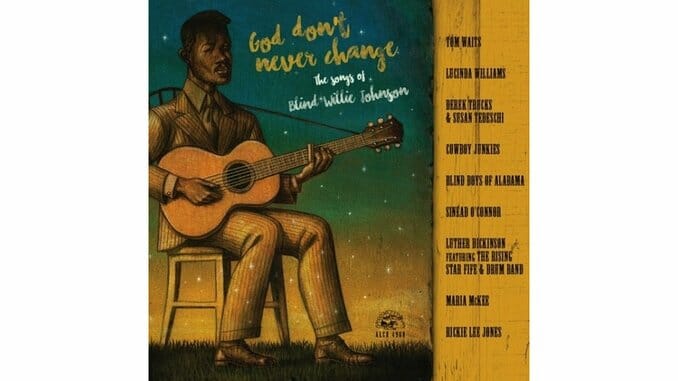

Various Artists: God Don’t Never Change: The Songs of Blind Willie Johnson

Music Reviews Various Artists

We got the blues all wrong. We trod all over what it was about. We took it and made it whatever we wanted it to be, rendering its real joys hopelessly obscure. The rockers came in and made the bluesman a tough-as-nails whiskey-slugging mystic. The folkies came in and made the bluesman a patronizing shorthand for the “old weird America.” The movies and the album art designers made the bluesman into pure iconography, the hard-living hard-luck black man standing alone on a road somewhere in the South, catching the midnight train to another town. And Columbia, well, they made the bluesman Robert Johnson.

And they tended to make the blues into somber music, which it usually wasn’t. The blues was fun music. People danced to the blues. Bluesmen played at country dances and they played at bars on Saturday night. It was entertainment; it was showbiz. It’s important to keep that in mind because very few of the old bluesmen are left to speak for themselves anymore. They’re mostly gone. It’s up to the curators to tell us the truth, and the curators would rather tell us about Robert Johnson again and again.

Robert Johnson, you understand, has a sales history.

But Blind Willie Johnson never sold anything. All of his CD reissues combined only add up to 86,000 copies. That superficially damns him as another scratchy old museum artifact for the hobbyists. And if you know his work, it’s enough to make you scream. He’s not just a shibboleth of the elite blues fan. He’s one of those artists who lifts you out of your room and takes you somewhere else. He makes you forget where and when you are.

It helps that his subject was eternity. He was a mean slide guitarist, but it’s his commitment to gospel that means you can enjoy Blind Willie Johnson and never listen to any other blues performer. His songs are songs of faith from the bottom of a man’s soul and the top of his conviction. He sang about God with a muscle, fire and grit that is unrivaled and impossible to replicate. Songs that will never grow old. It’s blood-and-guts religion, pure hard gospel, from a man who meant it and believed it.

He gets to you. So it’s easy to understand why someone would pour the better part of a decade into a tribute album for him, as producer Jeffrey Gaskill did with God Don’t Never Change: The Songs of Blind Willie Johnson. You hear one Blind Willie Johnson song and it’s just there with you forever. You want other people to hear it. You want other people to feel what you felt. But it’s hard to tell people to just listen to songs from nearly a century ago. You have to prove you care. You have to explain why it matters and find your own way of explaining why it’s worth your time. A tribute album to Blind Willie Johnson must be, above all else, an advertisement for Blind Willie Johnson.

And God Don’t Never Change is one hell of an ad campaign. It’s stacked from top to bottom with roots music icons who are actually called icons outside their press kits, like Tom Waits, Lucinda Williams, Cowboy Junkies and Lone Justice’s Maria McKee.

The big trap an album like this could fall into is the one the rockers and the folkies and the marketers so easily fall into: mythologizing the performer. And Blind Willie Johnson is easy to mythologize. He was born to unrelenting tragedy. His mother died young. His stepmother blinded him. He was desperately poor and sang in the street. His house burned down and he had no choice but to live in the ruins, and he died there. He didn’t even make it to 50.

That’s enough to make you weep—and a perfect breeding ground for the myth of the noble primitive that stalks the blues. “Oh, look at this poor magical being” instead of “wow, that man overcame more adversity than we can even conceive and he still became a world-class craftsman,” which Johnson was. Johnson did incredible things that took a lot of practice and determination and no magic whatsoever. “Let Your Light Shine On Me” is a soaring testament to the joy of faith, a work of monumental beauty that probably required a whole lot of road testing. “Dark Was The Night, Cold Was The Ground” infers all the pain and suffering of Christ at the Garden of Gethsemane without a single word of the original hymn spoken, which requires deep emotional intelligence and grasp of the material. You don’t get eternal without practice.

Thrillingly, this album avoids that trap. And there were a million opportunities to fall in.

What Blind Willie Johnson knew, and what this album knows, is that this songbook is meant to glorify God. Gospel music cannot be great, it cannot mean what it is supposed to mean and do what it is supposed to do, without a performer singing to the absolute top of their ability for God. God comes first. Not Blind Willie Johnson.

At this, God Don’t Never Change succeeds brilliantly on 10 of its 11 tracks. Tom Waits contributes two songs, “The Soul of a Man” and “John The Revelator,” and sings them with his usual power and credibility. He sounds a whole lot like a pre-war bluesman at this point, but he’s not doing an imitation of one. He just finally sounds like that. Waits could spend the whole rest of his career playing gospel traditionals just like this without a shred of self-consciousness and that would be just fine. This is his home.

Lucinda Williams also contributes two songs, “It’s Nobody’s Fault But Mine” and the title track, and we learn something her albums rarely tell us: she can kill a blues song dead. Her performances cut about as hard as they can cut, all fire scorch and whiskey roar.

Cowboy Junkies deliver the album’s most creative arrangement with a downright terrifying read of “Jesus Is Coming Soon,” a slice of apocalyptic Christianity about the Spanish flu of 1918. It is a death march, fittingly wracked with doom, since that flu killed about five percent of all the people on earth. On the chorus, Margo Timmins harmonizes with a sample of Johnson’s original, a trick that would be tasteless if it wasn’t done exactly right, and it is here. The full-band workout is a pleasant surprise, since loyalty to Blind Willie Johnson’s arrangements would be mere historical reenactment.

The Blind Boys of Alabama, meanwhile, contribute a lush and spirited version of the traditional “Motherless Children” (here called “Mother’s Children Have A Hard Time,” in keeping with Columbia’s historically unreliable labeling of blues song titles) with unaffected production and slide guitar from Jason Isbell.

The album’s biggest surprise is Sinéad O’Connor, who sings “Trouble Will Soon Be Over” with a passion and intensity that will bring you to your knees. It is one of her best performances, sanctified and holy and confrontational. Awesome in the Biblical sense.

But the best track belongs to Maria McKee, who performs Johnson’s iconic “Let Your Light Shine On Me.” She blows it out of the water. It calls back immediately to her days singing “This World Is Not My Home” with Lone Justice, and may be the finest vocal performance of her career. It conjures all the joy it conjured when Blind Willie Johnson sang it. McKee does her level best to remind us that it’s the message that makes this music work, not the performer, and succeeds beyond all expectations.

God Don’t Never Change falters in exactly one place: the last track, “Dark Was The Night, Cold Was The Ground.” When Blind Willie Johnson performed it as an instrumental, he had created something so pure and ethereal it exists outside of space and time. Rickie Lee Jones could never hope to replicate that, and she doesn’t try. But her vocals are fried, her phrasing is mangled; she’s doing theater. She’s not inhabiting the material like all the other performers were. She’s acting broken down when she isn’t. It sounds affected and false and it doesn’t wash. (Happily, it’s not the only vocal performance of the song that’s available. The late gospel singer Marion Williams did a beautiful version that didn’t fake anything at all.)

But it’s also the easiest Blind Willie Johnson song to mess up. It has the most baggage. Ry Cooder used it as the basis for the Paris, Texas soundtrack. It anchored Pasolini’s The Gospel According to St. Matthew. Hell, it’s on the Voyager probe in the middle of interstellar space. It has an intimidating legacy. It’s not like covering a normal song. It’s like trying to cover an ocean or a rock formation. It’s part of the earth. It might not be possible. So this misstep is forgivable on balance.

And it doesn’t change the fact that this is the best Americana album of the year. It reminds us all the way out here in 2016 that Blind Willie Johnson’s songs are still alive, and there is no better way to pay tribute to one of the finest American artists who ever lived.