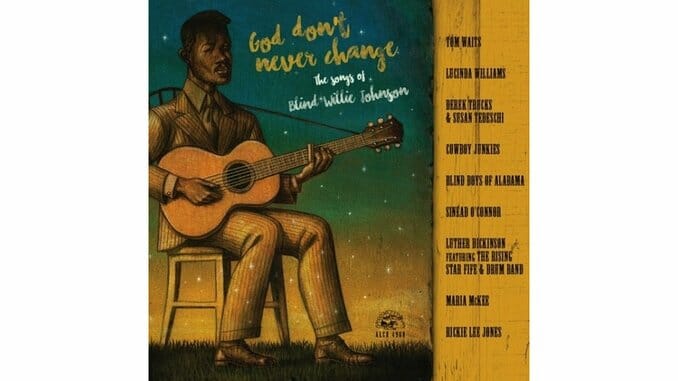

Various Artists: God Don’t Never Change: The Songs of Blind Willie Johnson

We got the blues all wrong. We trod all over what it was about. We took it and made it whatever we wanted it to be, rendering its real joys hopelessly obscure. The rockers came in and made the bluesman a tough-as-nails whiskey-slugging mystic. The folkies came in and made the bluesman a patronizing shorthand for the “old weird America.” The movies and the album art designers made the bluesman into pure iconography, the hard-living hard-luck black man standing alone on a road somewhere in the South, catching the midnight train to another town. And Columbia, well, they made the bluesman Robert Johnson.

And they tended to make the blues into somber music, which it usually wasn’t. The blues was fun music. People danced to the blues. Bluesmen played at country dances and they played at bars on Saturday night. It was entertainment; it was showbiz. It’s important to keep that in mind because very few of the old bluesmen are left to speak for themselves anymore. They’re mostly gone. It’s up to the curators to tell us the truth, and the curators would rather tell us about Robert Johnson again and again.

Robert Johnson, you understand, has a sales history.

But Blind Willie Johnson never sold anything. All of his CD reissues combined only add up to 86,000 copies. That superficially damns him as another scratchy old museum artifact for the hobbyists. And if you know his work, it’s enough to make you scream. He’s not just a shibboleth of the elite blues fan. He’s one of those artists who lifts you out of your room and takes you somewhere else. He makes you forget where and when you are.

It helps that his subject was eternity. He was a mean slide guitarist, but it’s his commitment to gospel that means you can enjoy Blind Willie Johnson and never listen to any other blues performer. His songs are songs of faith from the bottom of a man’s soul and the top of his conviction. He sang about God with a muscle, fire and grit that is unrivaled and impossible to replicate. Songs that will never grow old. It’s blood-and-guts religion, pure hard gospel, from a man who meant it and believed it.

He gets to you. So it’s easy to understand why someone would pour the better part of a decade into a tribute album for him, as producer Jeffrey Gaskill did with God Don’t Never Change: The Songs of Blind Willie Johnson. You hear one Blind Willie Johnson song and it’s just there with you forever. You want other people to hear it. You want other people to feel what you felt. But it’s hard to tell people to just listen to songs from nearly a century ago. You have to prove you care. You have to explain why it matters and find your own way of explaining why it’s worth your time. A tribute album to Blind Willie Johnson must be, above all else, an advertisement for Blind Willie Johnson.

And God Don’t Never Change is one hell of an ad campaign. It’s stacked from top to bottom with roots music icons who are actually called icons outside their press kits, like Tom Waits, Lucinda Williams, Cowboy Junkies and Lone Justice’s Maria McKee.

The big trap an album like this could fall into is the one the rockers and the folkies and the marketers so easily fall into: mythologizing the performer. And Blind Willie Johnson is easy to mythologize. He was born to unrelenting tragedy. His mother died young. His stepmother blinded him. He was desperately poor and sang in the street. His house burned down and he had no choice but to live in the ruins, and he died there. He didn’t even make it to 50.

That’s enough to make you weep—and a perfect breeding ground for the myth of the noble primitive that stalks the blues. “Oh, look at this poor magical being” instead of “wow, that man overcame more adversity than we can even conceive and he still became a world-class craftsman,” which Johnson was. Johnson did incredible things that took a lot of practice and determination and no magic whatsoever. “Let Your Light Shine On Me” is a soaring testament to the joy of faith, a work of monumental beauty that probably required a whole lot of road testing. “Dark Was The Night, Cold Was The Ground” infers all the pain and suffering of Christ at the Garden of Gethsemane without a single word of the original hymn spoken, which requires deep emotional intelligence and grasp of the material. You don’t get eternal without practice.

Thrillingly, this album avoids that trap. And there were a million opportunities to fall in.

What Blind Willie Johnson knew, and what this album knows, is that this songbook is meant to glorify God. Gospel music cannot be great, it cannot mean what it is supposed to mean and do what it is supposed to do, without a performer singing to the absolute top of their ability for God. God comes first. Not Blind Willie Johnson.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-