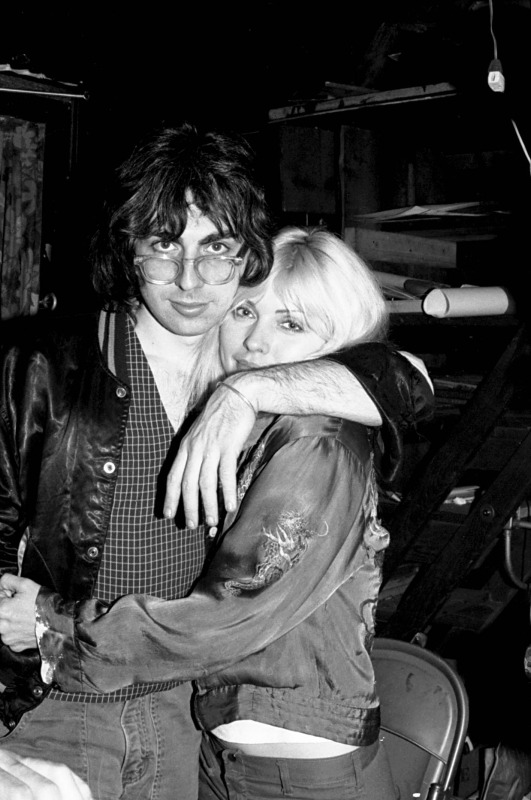

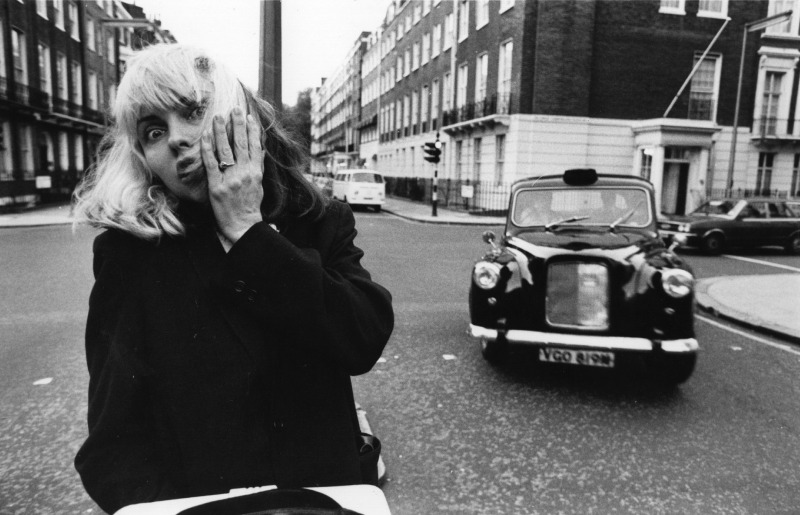

COVER STORY | Blondie Refuse to Vanish

Debbie Harry and Chris Stein speak with Paste about embracing girl-group pop's crossover into punk rock, navigating Blondie’s brand recognition in its prime, recording their first demos in a sweaty New York basement 50 years ago, the recent death of drummer Clem Burke, and the band’s new, John Congleton-produced album.

Photos by Gie Knaeps/Graham Morris/Suzan Carson/Michael Ochs Archives/Roberta Bayley/Redferns/Getty Images

Right now, Debbie Harry, who recently celebrated her 80th birthday, is dressed down, puttering around her home and “searching through a massive pile of stuff from every tour.” Since the ‘70s? Perhaps. During her spring cleaning in July, she pulls out a photograph of a man she believes to be guitarist Dave Edmunds. But after putting her glasses on, she realizes it’s Nick Lowe. A nearby Chris Stein calls her bandmate, old flame, and dear friend “a luddite” before sharing a laugh with her about it.

But before Debbie Harry was Debbie Harry, she was born Angela Trimble in Miami at the dawn of July in 1945. Three years later, gift shop owners Catherine and Richard Harry adopted her, renamed her Deborah Ann, and raised her in Jersey. She was a tomboy before her classmates at Hawthorne High School voted her “best looking” in 1963. Doo-wop music spilled into high school dances at the local firehouse, she remembers. One of the first songs she discovered on her own was Gerry Goffin and Carole King’s “Locomotion”; she bought 45s of Fats Domino and Little Richard; Percy Sledge’s “Thief in the Night” was her first favorite song. The radio taught Harry how to move, how to act. “My parents might have been on the edge of thinking, ‘This is never going to last,’” she chuckles.

After a move across the Hudson, Harry worked a number of odd jobs: BBC Radio office secretary, Union City go-go dancer, Max’s Kansas City hostess, Playboy Bunny. “That was quite an education and a real eyeful for me,” she says, referring to her time waitressing at Max’s before becoming a regular performer there. “There was a very illicit, sort of sexy vibe,” Stein notes. “That wasn’t at CBGB.” Harry adds that it’s what she had “always wanted to know about and be a part of,” that she “glorified in it” being a primary hang for New York’s art cohort. She remembers waiting on Andy Warhol (who would later become one of her greatest friends), Jefferson Airplane, and Mark Rothko. “All the artists went there because Mickey [Ruskin] would give them an open tab. At the end, when he would want to collect, he would settle for artwork, which, over time, became extremely valuable.”

Once her time at Max’s was over, Harry joined the Wind in the Willows, a band whose only album scored a modest #195 placement on the Billboard 200 57 years ago. Their producer, Artie Kornfeld, who used to sell soda pop at the Charlotte Coliseum so he could watch Elvis play, was hired as Woodstock’s promoter in 1969. By 1973, Harry had joined Elda Gentile and Amanda Jones in the Stilettos. I ask Stein, who went to the band’s first gig and became their permanent guitar player by the second, what he noticed first about Harry. Before he can get a word out, she volunteers to go into another room so he can answer honestly. Stein cracks up, before shrugging off her threat. “Debbie has this super charisma and magnetism,” he reflects. “I was there at an early moment of it, and I was very taken with her.”

Harry and Stein eventually became lovers and left the Stilettos to start their own group, alongside sisters Tish and Snooky Bellomo, called Angel and the Snake. This was 1974, and the name quickly changed to Blondie and the Banzai Babies, and then again to just Blondie—a nod to catcalls Harry got on the streets of New York after she bleached her hair. Even at the beginning, her tongue was stuck firmly in-cheek. The Bellomos were replaced by Gary Valentine, Clem Burke, and Jimmy Destri, but it was Harry’s relationship to Stein that stoked the embers at Blondie’s quarreling center. “Chris didn’t try to push anything on anybody,” Harry remembers. “He wasn’t trying to gain control or approve anything. He was there to play some music.” She turns to him, speaking directly: “It’s this completeness to your understanding of rock and roll, and pop music—and even classical music, or jazz. It was a terrific amount of feeling, and I really liked that. I loved that, actually.”

Stein, a student of the short-lived Mercer Arts Center and, as the New York Times called him, “the abstract mastermind of Blondie,” says he was “totally amused by” Harry and the Stilettos’ image and sound. “I thought they were very viable, for that moment in time.” When he first met Harry, Stein had just returned from England, where he was exposed to reggae music. He loved the deconstruction of it, where guys would break down old songs and make “new versions with new grooves.” Blondie screwed around with the bones of reggae on “Man Overboard” and “Attack of the Giant Ants” in 1976 before fully adopting it on “The Tide Is High” four years later, filling John Holt’s rocksteady original with cavities of calypso and new wave.

25 YEARS AFTER BLONDIE began playing daytime CBGB shows with crowds full of other bands and their entourages, music critics invented a rock revival in New York City to contend with the myths of mid-1970s Manhattan—lionizing the Strokes, Yeah Yeah Yeahs, the Rapture, and Interpol as the second-coming of a second-coming. But just as a post-9/11 real estate boom in Lower Manhattan and Williamsburg became a salve for a rotten music industry, out of the doldrums of Vietnam came a vibrant underground. No Wave, atonal noise, and art-rock were flavors of the month, germinating in the catalogues of Talking Heads, Patti Smith, Suicide, Teenage Jesus and the Jerks, and Lydia Lunch ten years after the arrivals of the Stooges and Velvet Underground. “It was so infectious and small,” Stein admits. “100 bands and that was it, and there were 20 A-list bands, out of all that. Everybody knew each other and went to each other’s gigs, and there was not much of a sense of the outside world or things going on elsewhere.”

I regale to Harry and Stein a story—first told to me by Bobby Baranowski of Werewolves, a short-lived, Dallas-bred, Andrew Loog Oldham-managed group that migrated to Manhattan after touring with the New York Dolls—about Nina Simone ripping up his band’s bar tab after they bowled over a Trude Heller’s crowd on a Wednesday night but drank more than they made at the door. Though most of their “celebrity encounters” came after Mike Chapman strapped a rocket to Blondie’s sound on Parallel Lines (save for Frankie Valli showing up to a gig and leaving his limo parked on the street), Stein recalls one folktale of similar uncertainty that lingered after one of the band’s sets: “There was a rumor that Jackie Onassis was at CBGBs. I can’t speak to the veracity of that, but it’s possible.” And that was the norm, Harry says, until record companies began coming to shows and a competitive bent polluted friendships. “Everybody realized, ‘Oh, my God, this could happen.’”

Maybe you’ve heard the story before, that it was “instant love at first sight” when Harry watched the New York Dolls play at the Mercer Arts Center. Stein says that they influenced “everybody on the scene,” but that David Johansen’s band “failed in America.” I ask him to elaborate. “They were too crazy,” he continues. “They had that album cover in semi-drag, and it was too much for people. It’s too raw and aggressive. Even MC5 and the Stooges—none of those acts really had the same level of success as the fucking Eagles, or whatever was going on.” Harry says that New York City, at the time, was othered by everyone living outside of it, thanks to urban decay, high unemployment rates, slashed social services, and the middle class’ “white flight.” “It was considered ‘dangerland,’” she remembers. “And, in a way, I guess it was.” Stein, Harry’s curt mouthpiece, calls the perception “lethal.”

“[Drag] wasn’t as accepted as it is today,” she argues.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-