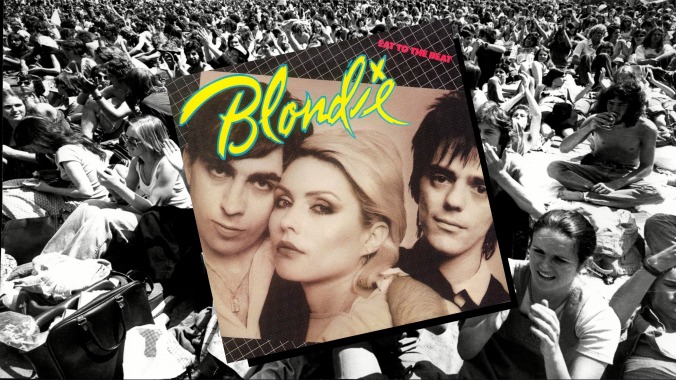

Time Capsule: Blondie, Eat to the Beat

Subscriber Exclusive

Every Saturday, Paste will be revisiting albums that came out before the magazine was founded in July 2002 and assessing its current cultural relevance. This week, we’re looking at Blondie’s follow-up to their magnum opus, a gutsy project that explored every genre from disco to reggae in a confection of sweet, poppy delight.

To this day, I fight with people over whether Blondie is a band or just Debbie Harry. It’s a hilarious argument that I can permanently shut down by playing “Atomic”—a song that would be incomplete without the slick seduction of Frank Infante and Chris Stein’s guitars, the relentless percussion from “Lord of the Fills” Clem Burke, the rhythmic lows of Nigel Harrison and, of course, the finesse of the song’s co-writer and band’s keyboardist, Jimmy Destri. As a fellow blonde myself, I tend to place all my attention on Harry and her magnetic presence, but Eat to the Beat would have never caught fire without the five other members of Blondie crafting the foundation for her to put an enchanting spell on.

Critics and fans are constantly pitting Blondie’s albums against each other. Both Plastic Letters and Eat to the Beat are vilified as failed recreations of their lauded predecessors (Blondie and Parallel Lines, respectively), yet Eat to the Beat refined the pop-rock sound the band introduced on Parallel Lines while also ambitiously mapping every genre from disco to reggae in a confection of sweet, poppy delight. It had the guts to explore outside the prominent genres of the time, including a lullaby and reggae amongst their beloved new wave pop rock. Eat to the Beat is bold and maybe a little ludicrous, but that kind of fearlessness is what I love most about Blondie.

I picture the record as the subdued, voguish older sister of Parallel Lines who, for all its brazen firepower, can never quite replicate the quiet cool of Eat to the Beat. That’s not to say I am discounting Parallel Lines as Blondie’s masterpiece; I’m just saying they occupy different booths in the same club. Eat to the Beat is leaning against a wall, smoking a cigarette, decked out in leather and wearing sunglasses inside the dimly lit club for no reason other than mystery; Parallel Lines is tearing up the stage with gutsy confidence in a shimmering mini dress with the tallest platform boots she could find. You need both to fill the whole thing out.

Eat to the Beat was the second installment in the Mike Chapman—an Australian pop record producer known best for his work with Blondie, the Sweet, Suzi Quatro and Mud—era of Blondie. Though Harry was initially skeptical about Chapman’s inclusion—even going as far as to state plainly, “[Blondie] were New York. [He] was L.A.”—he brought an urgency to that mimicked the snappy energy Blondie was trying to siphon from their favorite city and weave into their fourth record. He honed in on what made Parallel Lines so adored and upped the dramatics for Eat to the Beat.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-