Dijon Is R&B’s Past, Present, and Future on Baby

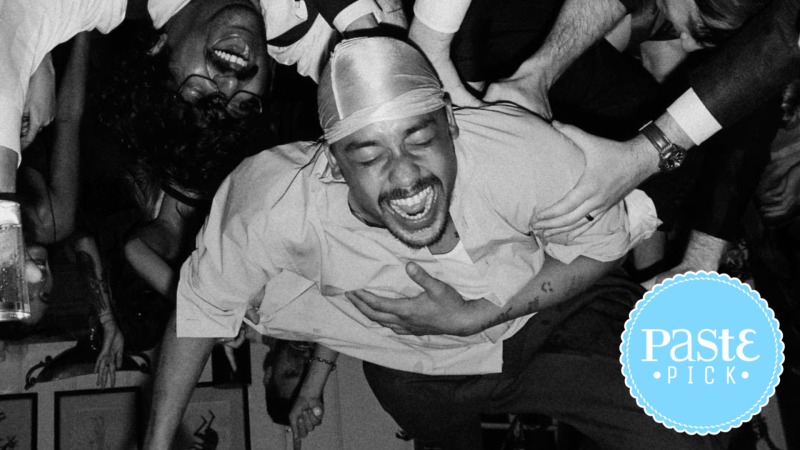

Paste Pick: The singer-producer’s second album isn’t a breakthrough or a comeback, but meteoric proof that his debut was star-making and his sound will command the genre’s next destiny without leaving any of its ancestry behind.

Showing up on a great Bon Iver song, co-writing part of Justin Bieber’s best solo album, and landing a part in the next Paul Thomas Anderson movie is a good resumé—great, even. But what if you did all of that and made a revelatory R&B record, too? Dijon, the 33-year-old, Baltimore-bred singer and producer, has taken the slow road to stardom. In 2017, he sang on Brockhampton’s “Summer.” During COVID, he and Charli XCX wrote “Pink Diamond” together. He’s worked with Kanye West, Jim-E Stack, Matt Champion, and Miso Extra. His taste is affectionate and deep-pocketed; not only has he cited Little Feat, Chaka Khan, The Band, and Lucinda Williams as influences, but he even managed to get John C. Reilly, Tobias Jesso Jr., and Becky and the Birds on a cypher together five years ago. His best friend, Mk.gee, exploded last year, nabbing year-end accolades and a Saturday Night Live performance for his troubles. Now, it’s Dijon’s time to detonate, and Baby is his nuclear missile.

But Baby isn’t a breakthrough or a comeback, it’s a confirmation. Dijon skyrocketed into view with the audacious Absolutely, a debut album with not only a kinetic, kitchen-table personality that AI could never replicate, but the dirtiest, most-emotional and immersive experience since James Blake’s first record 14 years ago. “Many Times,” to me, made Dijon a star, thanks to his splendid delivery of sensual, mewling frustration and a laundry list of sensory pressure points (“Strawberry, raspberry, candlelight, satellite, television, X-ray vision, ah! What’s it gonna take for you to listen?”), and an infectious, “I don’t really wanna talk about it, so many times you hurt me so much” chorus turned into proverb by hypnotic conviction left me wanting more.

But to listen to Dijon is to make yourself present. His body of work, albeit small, begs listeners to not only step into the world where he makes it, but to step into it repeatedly. He crafts songs like he’s singing them live, in front of hundreds, if not thousands (see: Absolutely’s companion film), and a standalone single two years ago, “coogie,” affirmed this, in its balance of smoke-covered vocal rasp and smoke-covered instrumental rapture you could practically touch. If Absolutely’s homespun production and randomness (he chose his collaborators for “The Stranger” by putting names in a hat, after all) felt theatrical, gimmicky, or kitschy four years ago, Baby casts Dijon’s idiosyncrasies in a proper, perfect light. The album was made at his home, with the help of Andrew Sarlo, Henry Kwapis, and Mk.gee, and the isolation is certain, felt as songs spill through doorways and in Dijon’s vocal mix, which often sounds like it’s coming from another, far emptier room.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-