The 100 Best Albums of 2024

Featuring Cindy Lee, Kendrick Lamar, Beyoncé, Thou, Waxahatchee, and more.

Paste’s 22nd Best Albums of the Year list, first compiled by the music team in a Google doc nearly 60 pages long, has arrived. 2024 was one for the books, and one of the best years of music of my life. Whether it was a pop record becoming so definitive that it had a whole season named after it, a two-hour album only available via YouTube and MP3 taking over the zeitgeist for a month, or some of this publication’s longtime favorite artists putting out career highlights, it’s hard to really quantify just how good these last 12 months have been, but we did it—and we’re ready to enshrine projects from Cindy Lee, Sturgill Simpson, ScHoolboy Q, Beyoncé, Thou, Kim Gordon, Bladee, Kendrick Lamar and countless others.

Combining staff picks, review scores and contributor votes, we’ve assembled a comprehensive list of our favorite full-length records released since December 1, 2023 (there will be a separate list for EPs). The genres range far and wide, touching everything from country to sludge metal to drill rap to hypnagogic pop, R&B, electronica, hardcore and big, tough, riffy rock ‘n’ roll. We aimed to leave no stone unturned and catch up on what we missed throughout the year, give more praise to the records we’ve loved since release day and showcase the vibrancy of such a diverse and talented crop of modern music. Here are the 100 best albums of 2024. Let us know in the comments which records we missed! —Matt Mitchell, Music Editor

100. Chelsea Wolfe: She Reaches Out to She Reaches Out to She

She Reaches Out to She Reaches Out to She is Chelsea Wolfe’s first solo album since her excellent 2019 LP Birth of Violence, and it’s at once a return to form and a venture towards something entirely new. The album’s title reflects its central theme: a conversation between past, present, and future selves, exploring rebirth and personal transformation. Darkwave textures and industrial rhythms are woven into a hypnotic tapestry of sound, every hushed whisper and muted croon thoroughly soaked in Wolfe’s signature gothic tonality even as she moves away from folk in favor of doom-core electronica. Even from the first track, “Whispers in the Echo Chamber” (an exemplary instance of Wolfe’s masterful command of tension and release), it’s evident that the record traffics in metamorphosis and the unknown. Ethereal vocals float above thunderous percussion and crystalline synth work as she sings, “Beyond reality, beyond the binary / Bathing in the blood of who I used to be … / Become my own fantasy / Twist the old self into poetry.” Her journey through sobriety emerges in the pulsing “House of Self-Undoing,” where vulnerability meets strength in a sublime collision of electronic and organic elements. When Wolfe ventures into trip-hop territory on “The Liminal” and “Salt,” she crafts an atmosphere both suffocating and liberating, demonstrating her ability to transmute personal transformation into sonic catharsis. The album’s closer “Dusk” serves as a perfect denouement, distilling the record’s themes of self-discovery within liminality into five minutes of transcendent dark ambience. She Reaches Out crafts an intricate dialogue between Wolfe’s past and future, pushing her sound into new territories while maintaining the dark, introspective core that has defined her work. “The unknowable mind, I feel it till it’s time,” Wolfe sings on “Unseen World.” “Grieve and redefine.” And that’s what She Reaches Out does so wonderfully, again and again and again: grieve and redefine. —Casey Epstein-Gross [Loma Vista]

She Reaches Out to She Reaches Out to She is Chelsea Wolfe’s first solo album since her excellent 2019 LP Birth of Violence, and it’s at once a return to form and a venture towards something entirely new. The album’s title reflects its central theme: a conversation between past, present, and future selves, exploring rebirth and personal transformation. Darkwave textures and industrial rhythms are woven into a hypnotic tapestry of sound, every hushed whisper and muted croon thoroughly soaked in Wolfe’s signature gothic tonality even as she moves away from folk in favor of doom-core electronica. Even from the first track, “Whispers in the Echo Chamber” (an exemplary instance of Wolfe’s masterful command of tension and release), it’s evident that the record traffics in metamorphosis and the unknown. Ethereal vocals float above thunderous percussion and crystalline synth work as she sings, “Beyond reality, beyond the binary / Bathing in the blood of who I used to be … / Become my own fantasy / Twist the old self into poetry.” Her journey through sobriety emerges in the pulsing “House of Self-Undoing,” where vulnerability meets strength in a sublime collision of electronic and organic elements. When Wolfe ventures into trip-hop territory on “The Liminal” and “Salt,” she crafts an atmosphere both suffocating and liberating, demonstrating her ability to transmute personal transformation into sonic catharsis. The album’s closer “Dusk” serves as a perfect denouement, distilling the record’s themes of self-discovery within liminality into five minutes of transcendent dark ambience. She Reaches Out crafts an intricate dialogue between Wolfe’s past and future, pushing her sound into new territories while maintaining the dark, introspective core that has defined her work. “The unknowable mind, I feel it till it’s time,” Wolfe sings on “Unseen World.” “Grieve and redefine.” And that’s what She Reaches Out does so wonderfully, again and again and again: grieve and redefine. —Casey Epstein-Gross [Loma Vista]

Read: “Chelsea Wolfe Embraces Her Inner Wisdom”

99. Doechii: Alligator Bites Never Heal

On “BOOM BAP,” the track at the center of Doechii’s latest project Alligator Bites Never Heal, the Tampa rapper yells the line “Get Top on the phone.” “Get ‘em on the phone!” she repeats, through Auto-Tune. Doechii isn’t messing around. She references Kendrick Lamar’s “untitled 02,” asserting herself as a part of the former TDE rapper’s lineage. It takes guts to align yourself as a descendant to Lamar so explicitly and confidently. But with Alligator Bites Never Heal, she pulls it off. The mixtape traverses pop-rap hits-in-waiting, house-infused struts, boom-bap, trap. You can hear Doechii’s hunger to prove herself. She’s sexy, goofy, confident, frustrated, clever, always three steps ahead. Trust her when she yells, “It’s everything / I’m everything!” On Alligator Bites Never Heal, Doechii comes into her own. There’s no one else more deserving of the TDE legacy. —Andy Steiner [TDE/Capitol Records]

On “BOOM BAP,” the track at the center of Doechii’s latest project Alligator Bites Never Heal, the Tampa rapper yells the line “Get Top on the phone.” “Get ‘em on the phone!” she repeats, through Auto-Tune. Doechii isn’t messing around. She references Kendrick Lamar’s “untitled 02,” asserting herself as a part of the former TDE rapper’s lineage. It takes guts to align yourself as a descendant to Lamar so explicitly and confidently. But with Alligator Bites Never Heal, she pulls it off. The mixtape traverses pop-rap hits-in-waiting, house-infused struts, boom-bap, trap. You can hear Doechii’s hunger to prove herself. She’s sexy, goofy, confident, frustrated, clever, always three steps ahead. Trust her when she yells, “It’s everything / I’m everything!” On Alligator Bites Never Heal, Doechii comes into her own. There’s no one else more deserving of the TDE legacy. —Andy Steiner [TDE/Capitol Records]

98. Feeling Figures: Everything Around You

Like Merlin, Montreal’s Feeling Figures are aging in reverse. Everything Around You, their excellent follow-up to last year’s sleeper underground hit Migration Music, is actually their first album—at least in terms of when it was recorded. Who knows what internal math pushed this one to the back of the line, but it was a smart call—it’s actually a stronger, deeper, and richer LP (and other comparatives, even), and one of the better underground rock records of the last few years. And you can be excused for just assuming the band’s from Australia, as they’ve been schooling the rest of the world on this kind of stuff for a couple of decades now. If you’re well-versed in the wayward permutations of unpopular music, you’ll know the score here immediately. Two guitars, bass, drums—as trad a lineup as possible—playing rock music, but not that kind of rock music; i.e., not something you would ever hear on classic rock radio, no matter how much time passes (those stations still exist, and they’re probably playing Vampire Weekend even as I type). Think White Light / White Heat, Wire’s second record, Sonic Youth, early Dinosaur Jr., and a ton of New Zealand and Australian bands, from The Clean all the way up to whatever new group Jake Robertson formed today. Feeling Figures fit squarely into that legacy, and Everything Around You is a fine addition to that canon. —Garrett Martin [K Records / Perennial Records]

Like Merlin, Montreal’s Feeling Figures are aging in reverse. Everything Around You, their excellent follow-up to last year’s sleeper underground hit Migration Music, is actually their first album—at least in terms of when it was recorded. Who knows what internal math pushed this one to the back of the line, but it was a smart call—it’s actually a stronger, deeper, and richer LP (and other comparatives, even), and one of the better underground rock records of the last few years. And you can be excused for just assuming the band’s from Australia, as they’ve been schooling the rest of the world on this kind of stuff for a couple of decades now. If you’re well-versed in the wayward permutations of unpopular music, you’ll know the score here immediately. Two guitars, bass, drums—as trad a lineup as possible—playing rock music, but not that kind of rock music; i.e., not something you would ever hear on classic rock radio, no matter how much time passes (those stations still exist, and they’re probably playing Vampire Weekend even as I type). Think White Light / White Heat, Wire’s second record, Sonic Youth, early Dinosaur Jr., and a ton of New Zealand and Australian bands, from The Clean all the way up to whatever new group Jake Robertson formed today. Feeling Figures fit squarely into that legacy, and Everything Around You is a fine addition to that canon. —Garrett Martin [K Records / Perennial Records]

97. Bladee: Cold Visions

Being a fan of Swedish rapper Bladee often feels like constantly asking yourself the question: Am I in too deep yet? Between his seven studio albums—to say nothing of three more full-length mixtapes, six collaborative records, six EPs and dozens of additional singles—constant collaborations with other Drain Gang and adjacent artists (Yung Lean, Ecco2k, Thaiboy Digital and co.), Bladee has spent the past 10 years creating a vocabulary of reference and self-reference through icy synths and laptop beeps. On Cold Visions, he gets to fully use it, calling back to snippets and lyrics of his old songs and records. It’s not just a pastiche of the Bladee lore, no, he’s got something new here. Bladee’s music has been glassy before, wrapped in bubble plastic, even, but on Cold Visions, everything shatters; we’re left falling down his hour-long fragmented rabbit hole and there’s no such thing as too deep. We’re there with him the whole way. “Only God Is Made Perfect,” arrives, announcing “drain gang” before he starts singing, “I used to sell—” and all of a sudden the beat drops out, and to replace whatever it is he was selling, the album title cuts in a cunning redaction. For all its overlaid parts, though, Cold Visions might just be Bladee’s most cohesive project to date, huddled under F1lthy’s dark, distorted production. He’s fighting through the haze of F1lthy’s manipulation, and the tension flaunts him at his most energized. That’s the thing about Cold Visions: It collapses the ironic distance that permeates most of Bladee’s music, but it doesn’t forsake the jokes. It’s always a tricky dance with him, and it’s impossible to take him any more seriously than he takes himself. But on this 2024 love letter to his Drain Gang, his persona and his mode of music-making, Bladee cements himself as a genuine artist. —Madelyn Dawson [Trash Island]

Being a fan of Swedish rapper Bladee often feels like constantly asking yourself the question: Am I in too deep yet? Between his seven studio albums—to say nothing of three more full-length mixtapes, six collaborative records, six EPs and dozens of additional singles—constant collaborations with other Drain Gang and adjacent artists (Yung Lean, Ecco2k, Thaiboy Digital and co.), Bladee has spent the past 10 years creating a vocabulary of reference and self-reference through icy synths and laptop beeps. On Cold Visions, he gets to fully use it, calling back to snippets and lyrics of his old songs and records. It’s not just a pastiche of the Bladee lore, no, he’s got something new here. Bladee’s music has been glassy before, wrapped in bubble plastic, even, but on Cold Visions, everything shatters; we’re left falling down his hour-long fragmented rabbit hole and there’s no such thing as too deep. We’re there with him the whole way. “Only God Is Made Perfect,” arrives, announcing “drain gang” before he starts singing, “I used to sell—” and all of a sudden the beat drops out, and to replace whatever it is he was selling, the album title cuts in a cunning redaction. For all its overlaid parts, though, Cold Visions might just be Bladee’s most cohesive project to date, huddled under F1lthy’s dark, distorted production. He’s fighting through the haze of F1lthy’s manipulation, and the tension flaunts him at his most energized. That’s the thing about Cold Visions: It collapses the ironic distance that permeates most of Bladee’s music, but it doesn’t forsake the jokes. It’s always a tricky dance with him, and it’s impossible to take him any more seriously than he takes himself. But on this 2024 love letter to his Drain Gang, his persona and his mode of music-making, Bladee cements himself as a genuine artist. —Madelyn Dawson [Trash Island]

96. Nia Archives: Silence Is Loud

As peak-pandemic malaise seemed to slowly leave the broader musical conversation in 2024, BRAT was hardly the only club-friendly album plumbing the depths of the soul to a heady, thumping beat. As a self-proclaimed “New Gen Junglist,” Producer and DJ Nia Archives first made critical waves by taking the U.K.’s long-storied love affair with drum and bass—as well as rave culture—and spreading the romance on a global scale with her dense, eclectic soundscapes. The 25-year-old’s first full-length Silence Is Loud layers heartbroken lyrics over breakneck production to craft one of the year’s most interesting debuts. Songs like the title track, “Unfinished Business” and “Forbidden Feelingz” are so packed with personality and hooks to spare that you might not even notice Archives spilling her guts on the dancefloor. Still, for anyone looking to scratch that bittersweet itch, Silence Is Loud stands toe-to-toe with the year’s most acclaimed dance music. —Elise Soutar [Island]

As peak-pandemic malaise seemed to slowly leave the broader musical conversation in 2024, BRAT was hardly the only club-friendly album plumbing the depths of the soul to a heady, thumping beat. As a self-proclaimed “New Gen Junglist,” Producer and DJ Nia Archives first made critical waves by taking the U.K.’s long-storied love affair with drum and bass—as well as rave culture—and spreading the romance on a global scale with her dense, eclectic soundscapes. The 25-year-old’s first full-length Silence Is Loud layers heartbroken lyrics over breakneck production to craft one of the year’s most interesting debuts. Songs like the title track, “Unfinished Business” and “Forbidden Feelingz” are so packed with personality and hooks to spare that you might not even notice Archives spilling her guts on the dancefloor. Still, for anyone looking to scratch that bittersweet itch, Silence Is Loud stands toe-to-toe with the year’s most acclaimed dance music. —Elise Soutar [Island]

95. Rosali: Bite Down

Of course, any band worth its weight benefits from songs with a strong gravitational pull, and Rosali dishes those out in heaping helpings. Like No Medium before it, Bite Down is packed wall to wall with tunes that are unsettled but unhurried, generous with melody, wandering but never lost, and reliably steady despite the never-ending twists and turns of an earthly existence. But above all, they are beautiful, broken and built around the kind of raw emotional uncertainty that will resonate with anyone who has ever lived, loved and/or lost. Bite Down’s highlights include “My Kind,” a kinetic, country-blues stomper that serves as evidence that Rosali is perfectly capable of a Waxahatchee-style arc if she chooses to pursue it, and “Hills on Fire,” a triumph of room-sound atmospherics and squirrelly guitar-isms that feels like watching a lightning storm crawl across a vast flatland, or perhaps childhood trauma streaking through an adult body. And while Bite Down has more approachable peaks, it ends with two tracks that echo both its stylistic range and its recurring themes of pain, self-reflection, healing and hope. First, “Change Is In The Form” builds a Crazy Horse-style crescendo around Rosali’s sing-song ruminations on the impermanence of life, which give way to “May It Be On Offer,” a quiet prayer for restoration and deliverance underpinned by long, droning tones. “There is hope upon me,” Rosali sings, with what sounds like fresh recognition in her voice. “There is reason to try.” Amen, indeed. That hard-won epiphany is the destination and Bite Down is the sound of the journey. We are fortunate Rosali has brought us all along for the ride. —Ben Salmon [Merge]

Of course, any band worth its weight benefits from songs with a strong gravitational pull, and Rosali dishes those out in heaping helpings. Like No Medium before it, Bite Down is packed wall to wall with tunes that are unsettled but unhurried, generous with melody, wandering but never lost, and reliably steady despite the never-ending twists and turns of an earthly existence. But above all, they are beautiful, broken and built around the kind of raw emotional uncertainty that will resonate with anyone who has ever lived, loved and/or lost. Bite Down’s highlights include “My Kind,” a kinetic, country-blues stomper that serves as evidence that Rosali is perfectly capable of a Waxahatchee-style arc if she chooses to pursue it, and “Hills on Fire,” a triumph of room-sound atmospherics and squirrelly guitar-isms that feels like watching a lightning storm crawl across a vast flatland, or perhaps childhood trauma streaking through an adult body. And while Bite Down has more approachable peaks, it ends with two tracks that echo both its stylistic range and its recurring themes of pain, self-reflection, healing and hope. First, “Change Is In The Form” builds a Crazy Horse-style crescendo around Rosali’s sing-song ruminations on the impermanence of life, which give way to “May It Be On Offer,” a quiet prayer for restoration and deliverance underpinned by long, droning tones. “There is hope upon me,” Rosali sings, with what sounds like fresh recognition in her voice. “There is reason to try.” Amen, indeed. That hard-won epiphany is the destination and Bite Down is the sound of the journey. We are fortunate Rosali has brought us all along for the ride. —Ben Salmon [Merge]

Read: “Rosali’s Vibrant, Sobering Vulnerability”

94. Young Jesus: The Fool

When John Rossiter isn’t telling a character’s story, he turns the focus on his own interior life. The songs on The Fool are honest at their core, and often quite heavy, dealing with serious topics. The record is an impressive and engaging work but not an easy listen. Its centerpiece, “Rich,” may well be Rossiter’s masterpiece, but you’ll want to take a moment after finishing it. There are a few different ideas held in the song, and while they are all distinct, they are also tangled together—but Rossiter does his best to parse them. Most strikingly, he sings bluntly about his own mental health struggles, and how mental illness and suicidality are passed down genetically. As he holds this idea in one hand, he also holds the inherited nature of generational wealth in the other—pondering how, though it can’t save people from all struggles, it affords them privilege. People who have family money are more often free to pursue careers in fields like the arts, and he acknowledges the open secret of it all. Song to song, there isn’t much sonic variation, and after the throw-everything-at-the-wall approach he took on Shepherd Head, the bare-boned arrangements here are refreshing. It’s unlikely that Rossiter will make another record like The Fool, but Young Jesus was already an unpredictable project before it, anyway. Though it can often leave you with a sense of discomfort, it’s remarkable that there isn’t a confrontational edge to The Fool. You don’t get the sense that Rossiter is trying to provoke you, necessarily, and you aren’t being asked to give him brownie points for being in touch with his own emotions. Rossiter has, instead, made something open—something that he needed to make, even if he didn’t know he ever could. —Eric Bennett [Saddle Creek]

When John Rossiter isn’t telling a character’s story, he turns the focus on his own interior life. The songs on The Fool are honest at their core, and often quite heavy, dealing with serious topics. The record is an impressive and engaging work but not an easy listen. Its centerpiece, “Rich,” may well be Rossiter’s masterpiece, but you’ll want to take a moment after finishing it. There are a few different ideas held in the song, and while they are all distinct, they are also tangled together—but Rossiter does his best to parse them. Most strikingly, he sings bluntly about his own mental health struggles, and how mental illness and suicidality are passed down genetically. As he holds this idea in one hand, he also holds the inherited nature of generational wealth in the other—pondering how, though it can’t save people from all struggles, it affords them privilege. People who have family money are more often free to pursue careers in fields like the arts, and he acknowledges the open secret of it all. Song to song, there isn’t much sonic variation, and after the throw-everything-at-the-wall approach he took on Shepherd Head, the bare-boned arrangements here are refreshing. It’s unlikely that Rossiter will make another record like The Fool, but Young Jesus was already an unpredictable project before it, anyway. Though it can often leave you with a sense of discomfort, it’s remarkable that there isn’t a confrontational edge to The Fool. You don’t get the sense that Rossiter is trying to provoke you, necessarily, and you aren’t being asked to give him brownie points for being in touch with his own emotions. Rossiter has, instead, made something open—something that he needed to make, even if he didn’t know he ever could. —Eric Bennett [Saddle Creek]

93. Empress Of: For Your Consideration

Lorely Rodriguez has often used her music project Empress Of as a shield, and on her fourth album For Your Consideration, she’s on a mission to restore confidence that love is still possible after despairing heartbreak. Though she maligns her former flame’s less-than-flattering traits (like discovering unfamiliar aromas on the sheets on “Lorelei”), she acknowledges her own flaws too; she can be too trusting and even takes on some of his flightiness post breakup. She lets voice soar, whisper, gasp, purr, and growl, distorting it to be delicate in one instance (“Cura”) to authoritative in the next (“Fácil”). It’s an album that finds pleasure in taking control but allowing oneself to achieve ecstasy in submission–even if it’s only for the night. —Jaeden Pinder [Major Arcana]

Lorely Rodriguez has often used her music project Empress Of as a shield, and on her fourth album For Your Consideration, she’s on a mission to restore confidence that love is still possible after despairing heartbreak. Though she maligns her former flame’s less-than-flattering traits (like discovering unfamiliar aromas on the sheets on “Lorelei”), she acknowledges her own flaws too; she can be too trusting and even takes on some of his flightiness post breakup. She lets voice soar, whisper, gasp, purr, and growl, distorting it to be delicate in one instance (“Cura”) to authoritative in the next (“Fácil”). It’s an album that finds pleasure in taking control but allowing oneself to achieve ecstasy in submission–even if it’s only for the night. —Jaeden Pinder [Major Arcana]

92. Hour: Ease the Work

I arrived at Hour’s Ease the Work a few months after its April release date, but the project has stuck with me (as most records on the Dear Life imprint do). A product of Michael Cormier-O’Leary’s Philly underground presence, Hour is 12 musicians focused on devotion to craft and gestures of good faith and unflinching grace. Ease the Work was recorded live across one week at the Greenwood Garden Playhouse on Peaks Island in Maine—a place you have to get to by ferry—before tourist season. Calling to mind the works of Bill Frisell, Scott Walker, the songs of Ease the Work summon reflections of everything from Led Zeppelin’s “The Rain Song” and the offerings of a minimalist Louisville chamber group called Rachel’s. The sonics are sweeping and skyscraping, as sound engineers Keith J. Nelson and Lucas Knapp capture floor-to-ceiling instrumental epics of improvisation and coalitions of punk, folk and classical music. —Matt Mitchell [Dear Life Records]

I arrived at Hour’s Ease the Work a few months after its April release date, but the project has stuck with me (as most records on the Dear Life imprint do). A product of Michael Cormier-O’Leary’s Philly underground presence, Hour is 12 musicians focused on devotion to craft and gestures of good faith and unflinching grace. Ease the Work was recorded live across one week at the Greenwood Garden Playhouse on Peaks Island in Maine—a place you have to get to by ferry—before tourist season. Calling to mind the works of Bill Frisell, Scott Walker, the songs of Ease the Work summon reflections of everything from Led Zeppelin’s “The Rain Song” and the offerings of a minimalist Louisville chamber group called Rachel’s. The sonics are sweeping and skyscraping, as sound engineers Keith J. Nelson and Lucas Knapp capture floor-to-ceiling instrumental epics of improvisation and coalitions of punk, folk and classical music. —Matt Mitchell [Dear Life Records]

91. Haley Heynderickx: Seed of a Seed

The Redwoods are just part of a big biological chorus on Seed of a Seed. You can hear the squish of the meadow beneath boots on “Foxglove,” the crashing of a wave on “Swoop” and the creeping proliferation of algae on “Mouth of a Flower.” From savoring a purple clover to tasting the sweet dew of morning, every breath of Seed is in communion with nature. It’s part of a tasting menu that also features the works of Walt Whitman and Barbara Kingsolver. The guitar work may sound uncomplicated at first blush, but that’s only because it’s so effortless. Haley Heynderickx is a true triple threat—vocalist, lyricist and guitarist—and her genius arrangements unfold upon repeat listens. Opener “Gemini” is a frantic self-takedown that features some of the most seductive strums of the album. The chords on “Jerry’s Song” pleasantly burble up over the smooth stones of bass, cello and layered vocals. And “Spit in the Sink” is a poem—about how we all try to create in spite of a tech-sick world that tells us creativity isn’t useful—that thanks to a sinewy melody proves itself as a song over and over again. There are too many other whip-smart lyrical strands to follow in one review, but one of Seed’s noteworthy themes is the miracle of a new day. Each new morning is “an offering,” as Heynderickx declares on “Sorry Fahey,” whose title is likely a nod to primitive guitar great John Fahey. Or, as she puts it on “Swoop,” “[t]here’s an artistry in the day to day.” And this kind of creativity isn’t found in a Zoom meeting or a social feed. It’s more likely in “free time” and “a hand next to mine,” both of which Heynderickx longs for on the title track. As she did on her first album I Need to Start a Garden, Heynderickx shows us that meaning can just easily be found in big existential questions and experiences as it can in the most minute details, down to a seed or a bug (her fixation on “The Bug Collector,” from her debut). The songs are as vast as canyons while also as fleeting as an ant. —Ellen Johnson [Mama Bird Recording Co.]

The Redwoods are just part of a big biological chorus on Seed of a Seed. You can hear the squish of the meadow beneath boots on “Foxglove,” the crashing of a wave on “Swoop” and the creeping proliferation of algae on “Mouth of a Flower.” From savoring a purple clover to tasting the sweet dew of morning, every breath of Seed is in communion with nature. It’s part of a tasting menu that also features the works of Walt Whitman and Barbara Kingsolver. The guitar work may sound uncomplicated at first blush, but that’s only because it’s so effortless. Haley Heynderickx is a true triple threat—vocalist, lyricist and guitarist—and her genius arrangements unfold upon repeat listens. Opener “Gemini” is a frantic self-takedown that features some of the most seductive strums of the album. The chords on “Jerry’s Song” pleasantly burble up over the smooth stones of bass, cello and layered vocals. And “Spit in the Sink” is a poem—about how we all try to create in spite of a tech-sick world that tells us creativity isn’t useful—that thanks to a sinewy melody proves itself as a song over and over again. There are too many other whip-smart lyrical strands to follow in one review, but one of Seed’s noteworthy themes is the miracle of a new day. Each new morning is “an offering,” as Heynderickx declares on “Sorry Fahey,” whose title is likely a nod to primitive guitar great John Fahey. Or, as she puts it on “Swoop,” “[t]here’s an artistry in the day to day.” And this kind of creativity isn’t found in a Zoom meeting or a social feed. It’s more likely in “free time” and “a hand next to mine,” both of which Heynderickx longs for on the title track. As she did on her first album I Need to Start a Garden, Heynderickx shows us that meaning can just easily be found in big existential questions and experiences as it can in the most minute details, down to a seed or a bug (her fixation on “The Bug Collector,” from her debut). The songs are as vast as canyons while also as fleeting as an ant. —Ellen Johnson [Mama Bird Recording Co.]

90. Parannoul: Sky Hundred

Last year, anonymous South Korean shoegazer Parannoul put out After the Magic, and it was one of the very best rock records of the year. The work encapsulates a new era in eyes-to-the-floor guitar-playing, as Parannoul infuses his shoegaze triumphs with bonkers electronica that upends any preconceptions we have about the genre in the first place. His new record, Sky Hundred, emphasizes that. “황금빛 강 (Gold River)” picks up right where After the Magic left off, fusing a backdrop of synthesizers with a banging wave of percussion and guitar melodies so damn colossal that you might just get lost in the tones. There are moments of pop perfection that skyscrape into an onslaught of blown-out, distorted sonic matrimony. It’s massive, just as the blown-out scrapes of “고통없이 (Painless)” is, capturing an aura of heartbroken hope. “No pain, no happiness,” Parannoul declares, bleaker than ever, remaining atypical but resound while stuffing tracklists with one-minute field recordings interludes (“No One Talks About It Anymore”), ceiling-shattering guitar capsules (“시계 (Backwards)”)and 14-minute scapes of punishing euphoria (“Evoke Me”). Sky Hundred is rid of context but as affecting as ever. —Matt Mitchell [POCLANOS]

Last year, anonymous South Korean shoegazer Parannoul put out After the Magic, and it was one of the very best rock records of the year. The work encapsulates a new era in eyes-to-the-floor guitar-playing, as Parannoul infuses his shoegaze triumphs with bonkers electronica that upends any preconceptions we have about the genre in the first place. His new record, Sky Hundred, emphasizes that. “황금빛 강 (Gold River)” picks up right where After the Magic left off, fusing a backdrop of synthesizers with a banging wave of percussion and guitar melodies so damn colossal that you might just get lost in the tones. There are moments of pop perfection that skyscrape into an onslaught of blown-out, distorted sonic matrimony. It’s massive, just as the blown-out scrapes of “고통없이 (Painless)” is, capturing an aura of heartbroken hope. “No pain, no happiness,” Parannoul declares, bleaker than ever, remaining atypical but resound while stuffing tracklists with one-minute field recordings interludes (“No One Talks About It Anymore”), ceiling-shattering guitar capsules (“시계 (Backwards)”)and 14-minute scapes of punishing euphoria (“Evoke Me”). Sky Hundred is rid of context but as affecting as ever. —Matt Mitchell [POCLANOS]

89. Rosie Tucker: Utopia Now!

In such a tangled web of late capitalist failures, trying to comment on the state of life on Earth in 2024 can be paralyzing; how do you talk about anything without talking about everything? LA singer-songwriter Rosie Tucker finds an effective methodology on their fifth LP, UTOPIA NOW!, where every lyric shines like a brilliant needle plucked from the rhetorical haystack and threaded effortlessly. “All I want is you—you—you—you—utopia now,” they sing on the title track, personal satisfaction and social revolution united in a perfect piece of tongue-in-cheek wordplay. In other songs, they personify U.S. imperialism as the archetypal girlboss (“White Savior Myth”) and catalog the thoughtless individual ambition that can spiral into an unsustainable force of destruction (“Paperclip Maximizer”) in perfect arrangements of syllables and indie rock melodies as permanent and irreducible as the plastic waste Tucker rails against so compellingly. Lest you question Tucker’s own place in the web, they offered this disclaimer in their Spotify bio, until recently: “I am able to give my time to music because i have a trust fund // i’m telling you because i think it is very gross the degree to which undisclosed generational wealth undergirds the whole music industry.” —Taylor Ruckle [Sentimental Records]

In such a tangled web of late capitalist failures, trying to comment on the state of life on Earth in 2024 can be paralyzing; how do you talk about anything without talking about everything? LA singer-songwriter Rosie Tucker finds an effective methodology on their fifth LP, UTOPIA NOW!, where every lyric shines like a brilliant needle plucked from the rhetorical haystack and threaded effortlessly. “All I want is you—you—you—you—utopia now,” they sing on the title track, personal satisfaction and social revolution united in a perfect piece of tongue-in-cheek wordplay. In other songs, they personify U.S. imperialism as the archetypal girlboss (“White Savior Myth”) and catalog the thoughtless individual ambition that can spiral into an unsustainable force of destruction (“Paperclip Maximizer”) in perfect arrangements of syllables and indie rock melodies as permanent and irreducible as the plastic waste Tucker rails against so compellingly. Lest you question Tucker’s own place in the web, they offered this disclaimer in their Spotify bio, until recently: “I am able to give my time to music because i have a trust fund // i’m telling you because i think it is very gross the degree to which undisclosed generational wealth undergirds the whole music industry.” —Taylor Ruckle [Sentimental Records]

88. claire rousay: sentiment

The pop that claire rousay constructs on sentiment may sound infinitely different than that which often gets labeled “pop,” but the faint outlines of song structures and deep, affective resonance tie it to pop as it’s understood today. Perhaps its closest relative might be the bedroom work of Orchid Tapes, who often utilized at-home production, found sound and experimental techniques with which to chart an emotional dialogue within fluid structures. sentiment makes perfect sense as pop in a context where the immersive compositions of Foxes In Fiction, the diaristic entries of Blithe Field and the extremities of katie dey are all understood as working with pop’s glorious and bendable toolbox. sentiment approaches such an act of exploration with warped vocals and tender-strummed guitar more than rousay’s albums typically feature, but they’re buttressed with recordings from the field that is her everyday life. There’s a cruelty to one’s self—an urge to secure fleeting moments of emotional security—that rousay narrates throughout sentiment unflinchingly. It’s uncomfortable, but her music often thrives in the uncomfortable. —Devon Chodzin [Thrill Jockey]

The pop that claire rousay constructs on sentiment may sound infinitely different than that which often gets labeled “pop,” but the faint outlines of song structures and deep, affective resonance tie it to pop as it’s understood today. Perhaps its closest relative might be the bedroom work of Orchid Tapes, who often utilized at-home production, found sound and experimental techniques with which to chart an emotional dialogue within fluid structures. sentiment makes perfect sense as pop in a context where the immersive compositions of Foxes In Fiction, the diaristic entries of Blithe Field and the extremities of katie dey are all understood as working with pop’s glorious and bendable toolbox. sentiment approaches such an act of exploration with warped vocals and tender-strummed guitar more than rousay’s albums typically feature, but they’re buttressed with recordings from the field that is her everyday life. There’s a cruelty to one’s self—an urge to secure fleeting moments of emotional security—that rousay narrates throughout sentiment unflinchingly. It’s uncomfortable, but her music often thrives in the uncomfortable. —Devon Chodzin [Thrill Jockey]

87. Rose Hotel: A Pawn Surrender

Atlanta singer-songwriter Jordan Reynolds took five years to follow up her self-released debut under the moniker Rose Hotel, and A Pawn Surrender was definitely worth the wait. At times angular and direct, she also ranges into spacey psych-folk, but either way the melodies head in unexpected directions as she lays her heart bare on these 10 tracks. The one-two punch of “Not Like That” and “King and a Pawn” in the middle of the album and closer “Illusion Anyway” should be popping up on Spotify playlists for anyone listening to indie music, but I don’t control the algorithms. This is one you’re probably going to have to queue up for yourself. —Josh Jackson [Strolling Bones]

Atlanta singer-songwriter Jordan Reynolds took five years to follow up her self-released debut under the moniker Rose Hotel, and A Pawn Surrender was definitely worth the wait. At times angular and direct, she also ranges into spacey psych-folk, but either way the melodies head in unexpected directions as she lays her heart bare on these 10 tracks. The one-two punch of “Not Like That” and “King and a Pawn” in the middle of the album and closer “Illusion Anyway” should be popping up on Spotify playlists for anyone listening to indie music, but I don’t control the algorithms. This is one you’re probably going to have to queue up for yourself. —Josh Jackson [Strolling Bones]

86. Yasmin Williams: Acadia

After listening to her parents’ Earth, Wind & Fire records and becoming entranced by the group’s song, “Kalimba Story,” Yasmin Williams tried to produce that sound on her acoustic guitar, laying it flat in her lap and learned to tap on it as if it were a piano. Eventually she obtained an actual kalimba and attached it to her guitar with Velcro so she could play both instruments during the same song. It wasn’t just that she used an unusual technique to produce an unusual sound; Williams soon demonstrated a gift for composing spellbinding instrumental melodies. That ability rises to a new level on her latest album, Acadia, with nine original compositions of greater complexity and length than ever before. She doesn’t play the kalimba on this project, but she uses her kalimba-derived tapping technique and such instruments as kora, calabash and banjo to keep the connection to Africa alive. At the same time, however, she expands the scope of her sound by inviting guests from different fields. A string quartet joins her on the seven-minute “Sisters,” while jazz stars Immanuel Wilkins and Marcus Gilmore pull her in their direction on “Malamu.” Darlingside and Aoife O’Donovan add vocals to two numbers, and two other numbers add synths. And Dom Flemons plays rhythm bones on the opening track, “Cliffwalk.” When integrated into Williams’s astonishing playing and composing, these new musical flavors make Acadia a 21st century rarity: a non-jazz, non-classical instrumental triumph. —Geoffrey Himes [Nonesuch]

After listening to her parents’ Earth, Wind & Fire records and becoming entranced by the group’s song, “Kalimba Story,” Yasmin Williams tried to produce that sound on her acoustic guitar, laying it flat in her lap and learned to tap on it as if it were a piano. Eventually she obtained an actual kalimba and attached it to her guitar with Velcro so she could play both instruments during the same song. It wasn’t just that she used an unusual technique to produce an unusual sound; Williams soon demonstrated a gift for composing spellbinding instrumental melodies. That ability rises to a new level on her latest album, Acadia, with nine original compositions of greater complexity and length than ever before. She doesn’t play the kalimba on this project, but she uses her kalimba-derived tapping technique and such instruments as kora, calabash and banjo to keep the connection to Africa alive. At the same time, however, she expands the scope of her sound by inviting guests from different fields. A string quartet joins her on the seven-minute “Sisters,” while jazz stars Immanuel Wilkins and Marcus Gilmore pull her in their direction on “Malamu.” Darlingside and Aoife O’Donovan add vocals to two numbers, and two other numbers add synths. And Dom Flemons plays rhythm bones on the opening track, “Cliffwalk.” When integrated into Williams’s astonishing playing and composing, these new musical flavors make Acadia a 21st century rarity: a non-jazz, non-classical instrumental triumph. —Geoffrey Himes [Nonesuch]

85. Shovel Dance Collective: The Shovel Dance

Shovel Dance Collective’s sonic archaeology seeks to re-contextualize centuries-old traditional performance with special attention to the marginal figures of the British Isles. As a nonet, their live performances are riveting, and their album The Shovel Dance best approximates their striking capabilities on record. The album is rich with drudgery and devastation, like on starvation song “Four Loom Weaver” or the oddly lugubrious jig “O’Sullivan’s March.” In these moments of bleakness, the sublime hits like a truck like in the rich harmonies and crescendos of “The Merry Golden Tree.” Amidst it all, there is some room for dance on the traditional Scottish song “Kissing’s Nae Sin/Newcastle/Portsmouth.” —Devon Chodzin [American Dreams]

Shovel Dance Collective’s sonic archaeology seeks to re-contextualize centuries-old traditional performance with special attention to the marginal figures of the British Isles. As a nonet, their live performances are riveting, and their album The Shovel Dance best approximates their striking capabilities on record. The album is rich with drudgery and devastation, like on starvation song “Four Loom Weaver” or the oddly lugubrious jig “O’Sullivan’s March.” In these moments of bleakness, the sublime hits like a truck like in the rich harmonies and crescendos of “The Merry Golden Tree.” Amidst it all, there is some room for dance on the traditional Scottish song “Kissing’s Nae Sin/Newcastle/Portsmouth.” —Devon Chodzin [American Dreams]

84. Rachel Chinouriri: What a Devastating Turn of Events

In a year of major pop records that make sweeping yet ultimately lackluster appeals toward confessionalism and vulnerability, the debut LP from British indie-pop newcomer Rachel Chinouriri is the year’s most emotionally and sonically striking coming-of-age concept album. Her music feels deeply personal and relatable without trying to be; its emotional impact never feels overwrought, and is always matched by a varied range of instrumental and production choices and Chinouriri’s engaging, elastic vocals. From the soaring, shoegazey meditation on imposter syndrome and leaving home (“The Hills”), to “Never Need Me,” the cinematic lead single and star-power proof-of-concept pop standout, to Chinouriri’s irreverent Cher Horowitz-inflected monologuing over the whistles and handclaps on “It Is What It Is,” to the breezy bravado on “Dumb Bitch Juice,” to the devastating diva balladry of “Robbed,” What a Devastating Turn of Events establishes Chinouriri as one of the most exciting young stars on the rise. —Grace Robins-Somerville [Parlophone]

In a year of major pop records that make sweeping yet ultimately lackluster appeals toward confessionalism and vulnerability, the debut LP from British indie-pop newcomer Rachel Chinouriri is the year’s most emotionally and sonically striking coming-of-age concept album. Her music feels deeply personal and relatable without trying to be; its emotional impact never feels overwrought, and is always matched by a varied range of instrumental and production choices and Chinouriri’s engaging, elastic vocals. From the soaring, shoegazey meditation on imposter syndrome and leaving home (“The Hills”), to “Never Need Me,” the cinematic lead single and star-power proof-of-concept pop standout, to Chinouriri’s irreverent Cher Horowitz-inflected monologuing over the whistles and handclaps on “It Is What It Is,” to the breezy bravado on “Dumb Bitch Juice,” to the devastating diva balladry of “Robbed,” What a Devastating Turn of Events establishes Chinouriri as one of the most exciting young stars on the rise. —Grace Robins-Somerville [Parlophone]

83. Ekko Astral: pink balloons

Considering the legacy of D.C.’s 40-year punk history—as groups like Bad Brains, Minor Threat, Fugazi, The Faith and Scream helped lay the hardcore foundation that’s still plugged into the city’s spirit—Ekko Astral fit right into a mold built for them to thrive in. And still, it feels like a small miracle that they’ve been able to break out like this. Born from Holzman and Hughes’ friendship after meeting each other as students at the University of Vermont, Ekko Astral embody the scene that made them—and, in an era where “scene” music is growing thinner and thinner, the release of pink balloons feels like a righteous and radical victory lap before the race has even started. And few bands have ever really achieved that sort of open-and-shut firepower. Normally it takes some groups a couple of records to get their wheels spinning; Ekko Astral and their “mascara mosh pit” sound are a beacon of joy and breaking points—through the noise of 11 tracks comes a resounding sense of urgent, non-negotiable optimism. What sticks out most about pink balloons is Ekko Astral’s commitment to singing like their generation speaks, which is how you get a barn-burning, circuit-breaking masher like “uwu type beat,” where Holzman, like a glitched-out, Kim Deal-like messenger, bemoans learning to love online and the “empty suit guys” who abuse TouchTunes at the bar. But such era-specific language and cultural references never register like they will become outdated as soon as the next wave of slang is built or the next lineage of celebrities grab hold of their 15 minutes of fame. Instead, like all good punk records we’ve been returning to for 40 years, the music of pink balloons comes across like an archive that captures a moment that will, someday, look different but sound the same. —Matt Mitchell [Topshelf]

Considering the legacy of D.C.’s 40-year punk history—as groups like Bad Brains, Minor Threat, Fugazi, The Faith and Scream helped lay the hardcore foundation that’s still plugged into the city’s spirit—Ekko Astral fit right into a mold built for them to thrive in. And still, it feels like a small miracle that they’ve been able to break out like this. Born from Holzman and Hughes’ friendship after meeting each other as students at the University of Vermont, Ekko Astral embody the scene that made them—and, in an era where “scene” music is growing thinner and thinner, the release of pink balloons feels like a righteous and radical victory lap before the race has even started. And few bands have ever really achieved that sort of open-and-shut firepower. Normally it takes some groups a couple of records to get their wheels spinning; Ekko Astral and their “mascara mosh pit” sound are a beacon of joy and breaking points—through the noise of 11 tracks comes a resounding sense of urgent, non-negotiable optimism. What sticks out most about pink balloons is Ekko Astral’s commitment to singing like their generation speaks, which is how you get a barn-burning, circuit-breaking masher like “uwu type beat,” where Holzman, like a glitched-out, Kim Deal-like messenger, bemoans learning to love online and the “empty suit guys” who abuse TouchTunes at the bar. But such era-specific language and cultural references never register like they will become outdated as soon as the next wave of slang is built or the next lineage of celebrities grab hold of their 15 minutes of fame. Instead, like all good punk records we’ve been returning to for 40 years, the music of pink balloons comes across like an archive that captures a moment that will, someday, look different but sound the same. —Matt Mitchell [Topshelf]

Read: “Ekko Astral: The Best of What’s Next”

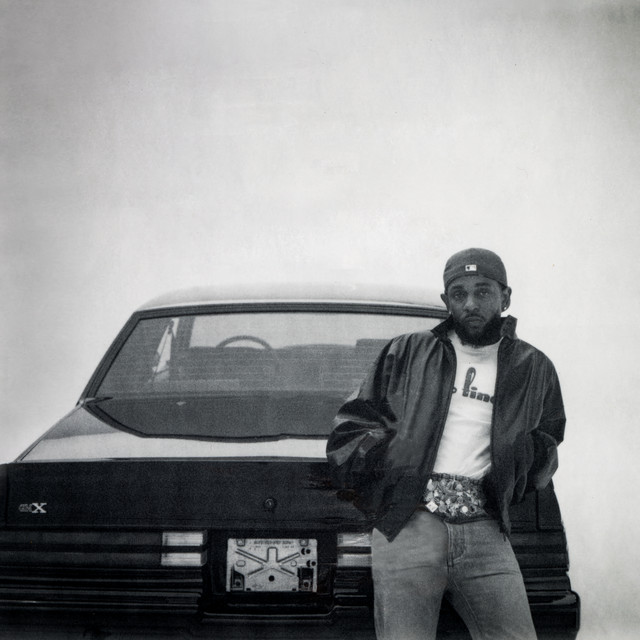

82. NxWorries: Why Lawd?

Coming into 2024, it had been nearly eight years since NxWorries last dropped a full-length project (Yes Lawd!), but Anderson .Paak and Knxwledge ended the drought in June with Why Lawd?, an R&B record that eclipses its predecessor in full. Calling upon Thundercat, H.E.R., Snoop Dogg, Charlie Wilson, Earl Sweatshirt and others, NxWorries transcend supergroup status by making a bonafide opus summoning the legacies of Monica, Black Dynamite, Motown and Miami Vice. Paak’s lyricism here is some of his best, as he presents himself as a flawed person, singing about survivor’s guilt (“MoveOn”), doomscrolling (“HereIAm”), emotional unavailablity (“FromHere”) and horniness (“Where I Go”) with a frankness that balances anger, pity and joy. Why Lawd? is a record about losing yourself, constructed with unflinching honesty and stitched together by Knxwledge’s whip-smart production and deeply present affection for gospel and Berry Gordy and all the solid gold left in-between. —Matt Mitchell [Stones Throw]

Coming into 2024, it had been nearly eight years since NxWorries last dropped a full-length project (Yes Lawd!), but Anderson .Paak and Knxwledge ended the drought in June with Why Lawd?, an R&B record that eclipses its predecessor in full. Calling upon Thundercat, H.E.R., Snoop Dogg, Charlie Wilson, Earl Sweatshirt and others, NxWorries transcend supergroup status by making a bonafide opus summoning the legacies of Monica, Black Dynamite, Motown and Miami Vice. Paak’s lyricism here is some of his best, as he presents himself as a flawed person, singing about survivor’s guilt (“MoveOn”), doomscrolling (“HereIAm”), emotional unavailablity (“FromHere”) and horniness (“Where I Go”) with a frankness that balances anger, pity and joy. Why Lawd? is a record about losing yourself, constructed with unflinching honesty and stitched together by Knxwledge’s whip-smart production and deeply present affection for gospel and Berry Gordy and all the solid gold left in-between. —Matt Mitchell [Stones Throw]

81. YATTA: PALM WINE

On PALM WINE, the Sierra Leonean-American composer, improviser, producer and vocalist YATTA leans into a folksy, jazzy-pop that is rich with electronic textures and snip-its from the world around her. Hits like “Fully Lost, Fully Found” and “Put Your Faith in God” play with ethereality and more propulsive motion, bringing forth a more inquisitive, unpredictable pop; “Too Good,” featuring fellow conceptual vocalist STEFA*, is especially groovy. PALM WINE links YATTA’s contemporary practice with that of her granduncle, S.E. Rogie, whose work popularized the West African-Portuguese synthesis genre Palm Wine. You can hear the playful, locomotive components of Palm Wine throughout YATTA’s compositions, but the way she darts between melodic and deconstructed pop, enriched by archival recordings and spoken word, makes for a well-rounded listen. —Devon Chodzin [PTP]

On PALM WINE, the Sierra Leonean-American composer, improviser, producer and vocalist YATTA leans into a folksy, jazzy-pop that is rich with electronic textures and snip-its from the world around her. Hits like “Fully Lost, Fully Found” and “Put Your Faith in God” play with ethereality and more propulsive motion, bringing forth a more inquisitive, unpredictable pop; “Too Good,” featuring fellow conceptual vocalist STEFA*, is especially groovy. PALM WINE links YATTA’s contemporary practice with that of her granduncle, S.E. Rogie, whose work popularized the West African-Portuguese synthesis genre Palm Wine. You can hear the playful, locomotive components of Palm Wine throughout YATTA’s compositions, but the way she darts between melodic and deconstructed pop, enriched by archival recordings and spoken word, makes for a well-rounded listen. —Devon Chodzin [PTP]

80. Brittany Howard: What Now

Relationship blues, healing, making sense of self-sabotaging patterns in friendships and romance are all explored through a jazzy, upbeat, audacious and vulnerable lens on What Now. The album is trimmed of subcutaneous sound, rounding out at just under 38-and-a-half minutes. Brittany Howard is here for a good time, not a long time, and bluesy earworms like “Prove It To You” and “Power To Undo” get under your skin, fizzle in your bloodstream and get your toes tapping and then, as cleanly as they began, wrap up neatly. There’s a confidence and vulnerability Howard fearlessly reveals on this album, which is more adventurous and riskier than Jaime. The Prince-inspired, funk-infused “Prove It To You,” with its brilliant, unabashed, funky soul, finds Howard contrasting the album’s soundscape by dialing back the drama, which is especially noticeable on closing track, “Every Color In Blue.” When Howard made her home in a spacious Nashville cottage just prior to the pandemic hitting, the garage became a space for collecting vintage recording gear and the ghosts of past greats, like James Brown, lurk within the buzzy guitar and buoyant bass in What Now. Contrasted with the nostalgic blues and funk of the 1970s is a glimmer of contemporary New Age elements—think bells, crystals, tarot, psychic energies and astrology. What Now addresses big themes—love, life and destruction—and, in places, it delivers a massive, eclectic sound. —Cat Woods [Island]

Relationship blues, healing, making sense of self-sabotaging patterns in friendships and romance are all explored through a jazzy, upbeat, audacious and vulnerable lens on What Now. The album is trimmed of subcutaneous sound, rounding out at just under 38-and-a-half minutes. Brittany Howard is here for a good time, not a long time, and bluesy earworms like “Prove It To You” and “Power To Undo” get under your skin, fizzle in your bloodstream and get your toes tapping and then, as cleanly as they began, wrap up neatly. There’s a confidence and vulnerability Howard fearlessly reveals on this album, which is more adventurous and riskier than Jaime. The Prince-inspired, funk-infused “Prove It To You,” with its brilliant, unabashed, funky soul, finds Howard contrasting the album’s soundscape by dialing back the drama, which is especially noticeable on closing track, “Every Color In Blue.” When Howard made her home in a spacious Nashville cottage just prior to the pandemic hitting, the garage became a space for collecting vintage recording gear and the ghosts of past greats, like James Brown, lurk within the buzzy guitar and buoyant bass in What Now. Contrasted with the nostalgic blues and funk of the 1970s is a glimmer of contemporary New Age elements—think bells, crystals, tarot, psychic energies and astrology. What Now addresses big themes—love, life and destruction—and, in places, it delivers a massive, eclectic sound. —Cat Woods [Island]

Read: “Brittany Howard’s Dreamworld”

79. Amaro Freitas: Y’Y

Y’Y, the latest composition from Brazilian jazz pianist Amaro Freitas, pays homage to the Amazon Forest and the rivers of Northern Brazil. With an ensemble of players like Jeff Parker, Shabaka Hutchings, Hamid Drake, Aniel Someillan and Brandee Younger, Freitas merges field recordings inspired by his time spent needling around in the Amazon basin with an engaging and kind response to the ongoing climate crisis. Y’Y makes good work of, as Freitas put it, recognizing nature “as our ancestor,” and chapters like “Mar de Cirandeiras” and “Gloriosa” are quietly powerful, as no piece of the band overpowers itself. Rather, it’s a living, breathing archival of the color and vibrancy just beyond us. With Freitas’s piano front-and-center, the quiet anthems of Y’Y rest on the shoulders of respect—and it’s the kind of ornate, empathetic musicality that never retreats, only surrendering itself to wonders surrounding it when chords and scales can no longer encapsulate the vividness. —Matt Mitchell [Psychic Hotline]

Y’Y, the latest composition from Brazilian jazz pianist Amaro Freitas, pays homage to the Amazon Forest and the rivers of Northern Brazil. With an ensemble of players like Jeff Parker, Shabaka Hutchings, Hamid Drake, Aniel Someillan and Brandee Younger, Freitas merges field recordings inspired by his time spent needling around in the Amazon basin with an engaging and kind response to the ongoing climate crisis. Y’Y makes good work of, as Freitas put it, recognizing nature “as our ancestor,” and chapters like “Mar de Cirandeiras” and “Gloriosa” are quietly powerful, as no piece of the band overpowers itself. Rather, it’s a living, breathing archival of the color and vibrancy just beyond us. With Freitas’s piano front-and-center, the quiet anthems of Y’Y rest on the shoulders of respect—and it’s the kind of ornate, empathetic musicality that never retreats, only surrendering itself to wonders surrounding it when chords and scales can no longer encapsulate the vividness. —Matt Mitchell [Psychic Hotline]

78. Chris Acker: Famous Lunch

The songs on Chris Acker’s Famous Lunch are gross and devastating, folk earworms that take cues from George Saunders in nastiness and Frank O’Hara in beauty. Though the title plays into the gnarly humor that often populates Acker’s songwriting, “Shit Surprise” is tender and sticky-sweet. “How we’d match our breath in the upstairs room,” he sings, “and we’d hold together ’til I smelled like you.” With Nikolai Shveitser’s pedal steel and Sam Gelband’s snare drum waltzing behind him, Acker enchants during the “but now it smells like I stepped in it, shit surprise” chorus that, when fused with the band’s backing harmonies, binds the whole song together. Acker, ever a man whose work is aglow with countless juxtapositions, fills a sentence beautifully with lines like “I feel her like a pulse in a cut on my thumb” and “I hear you brushing your tongue.” It’s a synergy hunkered down in delicious harmony. Jaw pops, bread slices and cilantro getting confused with parsley all come into focus, as Acker lets out one final thought: “I thought I’d grow up to love you by now.” The chugging melody and Acker’s curiosity on “Wouldn’t Do For You (Buddy)” makes for a striking gentleness: “These parentheses around our smiles hold that secret vague and tired,” he sings. “And I don’t ever speak of it, ‘cause nothing ever came of this. Those pomegranates I keep for you, lay them on the linen and they bleed right through.” Gelband’s snare hits rupture through the arrangement like a throbbing cut. Famous Lunch is as romantic as it is peculiar, comfortable in its own confusion and ready to love in its own light. “Stubborn Eyes” gets drunk on that sweet, sweet Ackerian earnestness, as he sings about a father and a son riffing through unorthodox, oft-toxic gestures of love. “Stole the motor off a mower at a country club, built a mini-bike and made it run,” he reckons. “No one would catch him in Evanston, except the hands of his dad that fell on him.” But all comes circling back through loud and quick talk, where feet are between lips and whims get followed “like birds carry seeds.” Caught someplace between Jerry Reed and Gram Parsons, Famous Lunch is a world ridden hard, put away wet and full of fragility, boundless, unpredictable love and one-liners that’ll make you cry, laugh and puke—in that order. —Matt Mitchell [Gar Hole Records]

The songs on Chris Acker’s Famous Lunch are gross and devastating, folk earworms that take cues from George Saunders in nastiness and Frank O’Hara in beauty. Though the title plays into the gnarly humor that often populates Acker’s songwriting, “Shit Surprise” is tender and sticky-sweet. “How we’d match our breath in the upstairs room,” he sings, “and we’d hold together ’til I smelled like you.” With Nikolai Shveitser’s pedal steel and Sam Gelband’s snare drum waltzing behind him, Acker enchants during the “but now it smells like I stepped in it, shit surprise” chorus that, when fused with the band’s backing harmonies, binds the whole song together. Acker, ever a man whose work is aglow with countless juxtapositions, fills a sentence beautifully with lines like “I feel her like a pulse in a cut on my thumb” and “I hear you brushing your tongue.” It’s a synergy hunkered down in delicious harmony. Jaw pops, bread slices and cilantro getting confused with parsley all come into focus, as Acker lets out one final thought: “I thought I’d grow up to love you by now.” The chugging melody and Acker’s curiosity on “Wouldn’t Do For You (Buddy)” makes for a striking gentleness: “These parentheses around our smiles hold that secret vague and tired,” he sings. “And I don’t ever speak of it, ‘cause nothing ever came of this. Those pomegranates I keep for you, lay them on the linen and they bleed right through.” Gelband’s snare hits rupture through the arrangement like a throbbing cut. Famous Lunch is as romantic as it is peculiar, comfortable in its own confusion and ready to love in its own light. “Stubborn Eyes” gets drunk on that sweet, sweet Ackerian earnestness, as he sings about a father and a son riffing through unorthodox, oft-toxic gestures of love. “Stole the motor off a mower at a country club, built a mini-bike and made it run,” he reckons. “No one would catch him in Evanston, except the hands of his dad that fell on him.” But all comes circling back through loud and quick talk, where feet are between lips and whims get followed “like birds carry seeds.” Caught someplace between Jerry Reed and Gram Parsons, Famous Lunch is a world ridden hard, put away wet and full of fragility, boundless, unpredictable love and one-liners that’ll make you cry, laugh and puke—in that order. —Matt Mitchell [Gar Hole Records]

77. Tex Patrello: Minotaur

In an indie landscape where so much new music can feel like a facsimile of a facsimile of a genre or scene long buried and gone, it’s rare to find something as startlingly inventive and strange as Minotaur, the debut full-length album by Dallas-based musician Tex Patrello. It’s a vulgar shotgun wedding between the sacred and profane set to swirls of surreal psychedelia—weaving bagpipes, glitchy layers of vocals and baby-voiced cheerleading chants into images of Americana, teen romance and pimps cruising outside fast-casual chain restaurants. From the limping stomp of “Long Lost Pimp” to the mechanical whirl of the outro on “Anything Goes” to the cinematic, orchestral swells of closer “De Kalb,” Patrello recounts each seedy vignette in an airy confection of a voice, conducting the chaos with so much conviction that you can’t help but be swept into her off-kilter orbit. After a while, the druggy delirium feels more like lovesickness, intoxicating in even its most sinister turns. It’s a challenging, swoon-worthy listen you’ll find yourself reaching for again and again—if only to marvel at how she got away with it in the first place. —Elise Soutar [Self-Released]

In an indie landscape where so much new music can feel like a facsimile of a facsimile of a genre or scene long buried and gone, it’s rare to find something as startlingly inventive and strange as Minotaur, the debut full-length album by Dallas-based musician Tex Patrello. It’s a vulgar shotgun wedding between the sacred and profane set to swirls of surreal psychedelia—weaving bagpipes, glitchy layers of vocals and baby-voiced cheerleading chants into images of Americana, teen romance and pimps cruising outside fast-casual chain restaurants. From the limping stomp of “Long Lost Pimp” to the mechanical whirl of the outro on “Anything Goes” to the cinematic, orchestral swells of closer “De Kalb,” Patrello recounts each seedy vignette in an airy confection of a voice, conducting the chaos with so much conviction that you can’t help but be swept into her off-kilter orbit. After a while, the druggy delirium feels more like lovesickness, intoxicating in even its most sinister turns. It’s a challenging, swoon-worthy listen you’ll find yourself reaching for again and again—if only to marvel at how she got away with it in the first place. —Elise Soutar [Self-Released]

76. Clairo: Charm

Where Sling narrowed, Charm expands; Clairo reprises her sophomore LP’s live analog instrumentation and doubles down on her hand of horns, woodwinds and synths. While Sling had a thin atmosphere—one that dispersed like smoke around a fire, sort of hiding her hyper-compressed vocals behind the orchestration—Charm finds her crisper than ever. She’s clear, upfront and conducting the show with co-producer Leon Michels of the lo-fi soul jazz outfit El Michels Affair and of Dan Auerbach’s psych-rock band the Arcs. After isolating, Clairo is even more lyrically present, finally emerging from her shell on slow waltz “Terrapin.” “We’re all afraid and shy away,” she reckons, “but now I find I guess I don’t shy.” Like Sling, most songs on Charm are still only a slight foot tap. Flutes often become harmonies. Harmonies become more harmonies, as vocals are double-tracked and layered over each other like that of Elliott Smith or Judee Sill. Now, with assistance from players in the Menahan Street Band, Charm is anchored by more psychedelic and jazzy undertones—a clear example of Michels’s influence. On “Echo,” a stuttering organ and dripping tremolo creates something like Portishead if they were a lounge band, as does the trip-hop beat—created from Clairo’s own giggle—in “Second Nature,” which swivels alongside bouncing staccato keys. “Our love is meant to be shared / While our love goes nowhere” sings Clairo in “Echo,” before the song pulses into a vamp. “Juna” similarly swings, as a twinkling piano rises and falls like a fluttering stomach. Clairo gets a mouth trumpet solo before a full band—with real trumpets—comes in and soars, letting the butterflies take flight.“I don’t get too intimate / Why would I let you in?” she hesitates. “But, I think again.” —Sam Small [Self-Released]

Where Sling narrowed, Charm expands; Clairo reprises her sophomore LP’s live analog instrumentation and doubles down on her hand of horns, woodwinds and synths. While Sling had a thin atmosphere—one that dispersed like smoke around a fire, sort of hiding her hyper-compressed vocals behind the orchestration—Charm finds her crisper than ever. She’s clear, upfront and conducting the show with co-producer Leon Michels of the lo-fi soul jazz outfit El Michels Affair and of Dan Auerbach’s psych-rock band the Arcs. After isolating, Clairo is even more lyrically present, finally emerging from her shell on slow waltz “Terrapin.” “We’re all afraid and shy away,” she reckons, “but now I find I guess I don’t shy.” Like Sling, most songs on Charm are still only a slight foot tap. Flutes often become harmonies. Harmonies become more harmonies, as vocals are double-tracked and layered over each other like that of Elliott Smith or Judee Sill. Now, with assistance from players in the Menahan Street Band, Charm is anchored by more psychedelic and jazzy undertones—a clear example of Michels’s influence. On “Echo,” a stuttering organ and dripping tremolo creates something like Portishead if they were a lounge band, as does the trip-hop beat—created from Clairo’s own giggle—in “Second Nature,” which swivels alongside bouncing staccato keys. “Our love is meant to be shared / While our love goes nowhere” sings Clairo in “Echo,” before the song pulses into a vamp. “Juna” similarly swings, as a twinkling piano rises and falls like a fluttering stomach. Clairo gets a mouth trumpet solo before a full band—with real trumpets—comes in and soars, letting the butterflies take flight.“I don’t get too intimate / Why would I let you in?” she hesitates. “But, I think again.” —Sam Small [Self-Released]

75. 1010benja: Ten Total

Years after making his grand entrance with 2017’s “Boofiness,” 1010Benja’s full-length debut arrived in the form of Ten Total. It encompasses his variegated, eclectic influences, which include everyone from Hideo Kojima to John Frusciante, in a concise, ten-track (of course!) package. He’ll go from acrobatic raps about reading Alan Moore, to gospel belts on “Twin,” to nonsensical onomatopoeia on “Penta.” As its name implies, Ten Total captures 1010’s totality. It’s not an easy task. —Grant Sharples [Three Six Zero]

Years after making his grand entrance with 2017’s “Boofiness,” 1010Benja’s full-length debut arrived in the form of Ten Total. It encompasses his variegated, eclectic influences, which include everyone from Hideo Kojima to John Frusciante, in a concise, ten-track (of course!) package. He’ll go from acrobatic raps about reading Alan Moore, to gospel belts on “Twin,” to nonsensical onomatopoeia on “Penta.” As its name implies, Ten Total captures 1010’s totality. It’s not an easy task. —Grant Sharples [Three Six Zero]

74. Trent Reznor & Atticus Ross: Challengers

I don’t usually care about tennis, but put Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross’s propulsive, throbbing soundtrack to Challengers behind anything, even paint drying, and you’ll find yourself riveted. This is Reznor and Ross’ second collaboration with director Luca Guadagnino, the first being Bones and All, but the Challengers album easily outshines that one with its kinetic, Berlin techno-inspired sound. The fun, sexy tennis movie has fun, sexy music to match: The ping-ponging beat of “Brutalizer” gets the heart racing from the get-go, and the neon pangs of synth on “Yeah x10” transform any quotidian moment into a laser-focused, all-or-nothing battle for the ages. The pair masterfully build tension across the soundtrack, allowing the heat to abate for songs like the aptly named “Lullaby” and the choral serenity of “Friday Afternoons, Op. 7: A New Year Carol.” Needless to say, Challengers is an ace of an album. —Clare Martin [Milan]

I don’t usually care about tennis, but put Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross’s propulsive, throbbing soundtrack to Challengers behind anything, even paint drying, and you’ll find yourself riveted. This is Reznor and Ross’ second collaboration with director Luca Guadagnino, the first being Bones and All, but the Challengers album easily outshines that one with its kinetic, Berlin techno-inspired sound. The fun, sexy tennis movie has fun, sexy music to match: The ping-ponging beat of “Brutalizer” gets the heart racing from the get-go, and the neon pangs of synth on “Yeah x10” transform any quotidian moment into a laser-focused, all-or-nothing battle for the ages. The pair masterfully build tension across the soundtrack, allowing the heat to abate for songs like the aptly named “Lullaby” and the choral serenity of “Friday Afternoons, Op. 7: A New Year Carol.” Needless to say, Challengers is an ace of an album. —Clare Martin [Milan]

73. Mount Eerie: Night Palace

With Night Palace, Phil Elverum builds a bridge between his past and present, creating an album that feels both like a summation and an evolution of his storied career. Mount Eerie’s 81-minute opus is a whopping 26 tracks (including a 12-minute spoken-word piece!), all in service of weaving together Elverum’s diverse musical threads—spanning the raw, elemental force of early Mount Eerie, the stark minimalism of his recent grief-centered work, and newfound sonic territories. Tracks like “Broom of Wind” shimmer with layered arrangements, easily gliding through hope and sorrow, while the jarring, noise-heavy “Swallowed Alive” feels like a return to “Samurai Sword” form (of The Glow Pt. 2), interrupting the gentleness of the songs around it and forcing the listener back to cognizance—but it, too, boasts a newness: a feature from Elverum’s young daughter, Agathe, simply because, as he put it, “I knew that I couldn’t scream as well as she could.” Night Palace treks through the varying tragedies of life and living it: spanning Alzheimer’s to colonization, individual grief to mass genocide. But the record is in constant conversation with not only the world around but the world within, and even the world that came before; self-referential tracks like “I Saw Another Bird” cheekily dismiss the meaning Elverum himself once granted to birds in his 2017 masterwork A Crow Looked at Me (“So what? I saw another raven,” the song begins, “I see them all the time”) before doubling down on the general feeling of it all, insisting that “There is another world inside this one / It shines: / These birds trying for my attention / And my wordless reply.” From the sprawling, experimental folk of The Glow, Pt. 2 (which Elverum released under the moniker of The Microphones) to the devastating quietude of A Crow Looked at Me, Elverum has always been a master of crafting intimate universes, where existential musings meet the tangible details of everyday life. Night Palace revisits these themes with a newfound sense of expansiveness and reconciliation—a willingness to embrace complexity without being consumed by it, and perhaps that makes all the difference. —Casey Epstein-Gross [P.W. Elverum & Sun]

With Night Palace, Phil Elverum builds a bridge between his past and present, creating an album that feels both like a summation and an evolution of his storied career. Mount Eerie’s 81-minute opus is a whopping 26 tracks (including a 12-minute spoken-word piece!), all in service of weaving together Elverum’s diverse musical threads—spanning the raw, elemental force of early Mount Eerie, the stark minimalism of his recent grief-centered work, and newfound sonic territories. Tracks like “Broom of Wind” shimmer with layered arrangements, easily gliding through hope and sorrow, while the jarring, noise-heavy “Swallowed Alive” feels like a return to “Samurai Sword” form (of The Glow Pt. 2), interrupting the gentleness of the songs around it and forcing the listener back to cognizance—but it, too, boasts a newness: a feature from Elverum’s young daughter, Agathe, simply because, as he put it, “I knew that I couldn’t scream as well as she could.” Night Palace treks through the varying tragedies of life and living it: spanning Alzheimer’s to colonization, individual grief to mass genocide. But the record is in constant conversation with not only the world around but the world within, and even the world that came before; self-referential tracks like “I Saw Another Bird” cheekily dismiss the meaning Elverum himself once granted to birds in his 2017 masterwork A Crow Looked at Me (“So what? I saw another raven,” the song begins, “I see them all the time”) before doubling down on the general feeling of it all, insisting that “There is another world inside this one / It shines: / These birds trying for my attention / And my wordless reply.” From the sprawling, experimental folk of The Glow, Pt. 2 (which Elverum released under the moniker of The Microphones) to the devastating quietude of A Crow Looked at Me, Elverum has always been a master of crafting intimate universes, where existential musings meet the tangible details of everyday life. Night Palace revisits these themes with a newfound sense of expansiveness and reconciliation—a willingness to embrace complexity without being consumed by it, and perhaps that makes all the difference. —Casey Epstein-Gross [P.W. Elverum & Sun]

Read: “The Rituals of Mount Eerie”

72. Still House Plants: If I don’t make it, I love u

Still House Plants have gathered some steam as a trio of artsy freaks whose experimental take on rock is impossible to ignore. With If I don’t make it, I love u, the band’s wobbly rhythms and peculiar lyrics are on full display, each element presented equally so that your consciousness bounces between Finlay Clark’s guitar, David Kennedy’s drums and Jess Hickie-Kallenbach’s vocals. That said, the way Hickie-Kallenbach can draw out one word into a true focal point really sells the music: How she hangs onto “called” in the line “I wish I was called Makita” on “M M M” is enrapturing. The way she barrels through the repeated phrase “Words of a boring angel” on “MORE BOY” feels like little fireworks in your ears. The emotion is slowly explosive, coming in bursts throughout, awkwardly and inconveniently, much more true to form. —Devon Chodzin [Bison Records]

Still House Plants have gathered some steam as a trio of artsy freaks whose experimental take on rock is impossible to ignore. With If I don’t make it, I love u, the band’s wobbly rhythms and peculiar lyrics are on full display, each element presented equally so that your consciousness bounces between Finlay Clark’s guitar, David Kennedy’s drums and Jess Hickie-Kallenbach’s vocals. That said, the way Hickie-Kallenbach can draw out one word into a true focal point really sells the music: How she hangs onto “called” in the line “I wish I was called Makita” on “M M M” is enrapturing. The way she barrels through the repeated phrase “Words of a boring angel” on “MORE BOY” feels like little fireworks in your ears. The emotion is slowly explosive, coming in bursts throughout, awkwardly and inconveniently, much more true to form. —Devon Chodzin [Bison Records]

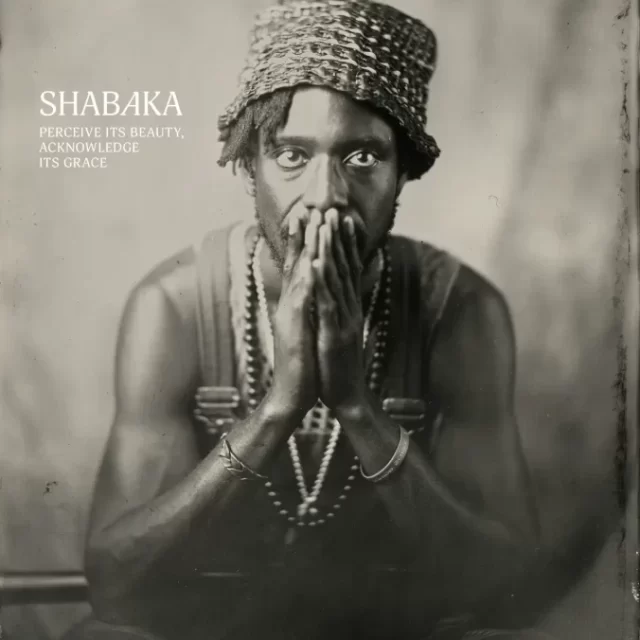

71. Vampire Weekend: Only God Was Above Us