Fontaines D.C. Learn, Rise and Return

In our latest Digital Cover Story, Grian Chatten and Carlos O’Connell talk sartorial and musical transformations, finding comfort in expression, and the Dublin quintet’s fourth LP, Romance.

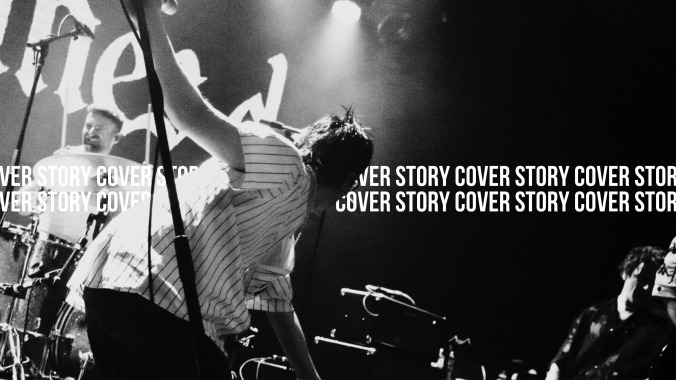

Photo by Deanie Chen

There’s a moment in an antsy, overheated crowd waiting for Fontaines D.C.’s one-off performance in the former Polish National Home in North Brooklyn on a May night where a small chorus of voices breaks the temperature and everyone’s backs straighten. As we shift from foot to foot for the millionth time in the last hour or so, Sinéad O’Connor’s “Troy” starts playing over Warsaw’s PA system. I feel my lips almost unconsciously start to move with its hushed opening verse. As the song begins to build in the second verse, my jaw opens wider, my chin lifts and my voice gets louder to sing “I swear I didn’t mean those things I said” along with her. The movement forces me to look up to watch a few people around me, mostly older women, drop their jaws to sing that first line of a voice raised too—crying out for Sinéad’s Dublin drowning in rain while we melt in the grimy onset of a New York summer. Shared home city between the artist we heard and the band we were about to hear aside, I had a feeling it would be the last song to play before Fontaines D.C. finally took the stage.

Maybe I had that feeling because I’d heard frontman Grian Chatten speak about “Troy” before. Just last year, he deemed the track “the most inspiring kind of art that you can surround yourself with.” Still, that night I heard “Troy” and thought about Romance, the band’s then-recently-announced fourth album Romance, and how the two artists in question handle that title phrase. There is so much O’Connor understood before the rest of us did and was ballsy enough to say in real time. Even if you just focus on the songwriting, she knew that in our current world—often a terrifying, bloodless place—there are no more pure love songs and no true expressions of despair. There is now only art that captures us in flux, ricocheting between the two chaotic states.

True to my prediction, once Sinéad O’Connor’s voice crescendos halfway through the song and fades, the lights dim for the opening notes of “Romance,” the record’s title track and effective prelude, propped up over a lumbering, ominous guitar line and its tinny toy piano counterpart. As soon as the song thunders to a close, guitarists Carlos O’Connell and Conor Curley, bassist Conor Deegan III, drummer Tom Coll and Chatten finally arrive, opening with “Nabakov,” the closer from 2022’s Skinty Fia. Two new songs slot perfectly against raucous favorites from the band’s 2019 debut Dogrel, and once a pit opens up in the center of the crowd, everyone moves—either to dance or to migrate towards the ornate walls on either side of the hall to avoid getting jostled.

Amid the restless crowd, a girl I don’t know standing behind me has her hand clawing at the very top of my spine, trying to keep her balance. “Life ain’t always empty,” she shrieks directly into my ear along with the band as they launch into the title track of 2020’s A Hero’s Death, the hand on my back now feeling more like an offering of rhapsodic physical reassurance than a safety precaution, “Life ain’t always empty.”

Two days earlier, a much calmer Grian Chatten and I sit on the terraced patio in front of the band’s hotel, a short walk from the venue in Brooklyn’s Williamsburg neighborhood. It’s one of the first noticeably warm days of the year, long before the seemingly never-ending heatwave the city finds itself in come August, when Romance will finally be released. Chatten is wearing the same silver wraparound sunglasses he will also don on the following night’s Tonight Show performance and at the Warsaw show the night after that. As we reach the end of our allotted interview time, I jokingly ask if I get an extra few minutes to speak with him, as he walked in for our time slot a few minutes late, but he stops me with a warm “Yeah, go for it,” before looking at me sheepishly. “Walking in late with my fucking L.A. shades and iced coffee…” he mutters, as if to scold himself, looking back down at the still-full beverage in question.

Even for their relatively casual press day, the band are decked out in the flashy, ‘90s-inspired duds which have demarcated the beginning of a new band era in performances and pictures and turned fans’ heads in the process. Carlos O’Connell is the first to meet me in the hotel lobby earlier that afternoon, walking down in search of coffee wearing baggy, black lace pants and with his dyed pink hair twisted to frame his face. Where he holds the crowd’s rapture with the swing of his arm on a stage, the professionals with espressos intently tapping at laptops around us don’t even flinch, having no interest in rock stars—which Fontaines D.C surely are at this point, if the term can still be used. It’s difficult to think of more than a handful of guitar bands who have ascended to similar heights in the last decade or so, marking them as an anomaly—a fact which they seem acutely aware of.

The thing is, the transformation—whether sartorial or musical—feels earned. When the band first emerged in an incessant wave of post-punk bands from the other side of the Atlantic, they were fairly easy to lump in with their fellow critically-acclaimed peers if you were just skimming the surface of what they presented. Yet, with each subsequent release, it felt increasingly reductive to call the band “guitar music.” Where those who would once be considered contemporaries may have struggled to evolve, few things have struck me in my time writing about music like hearing and dissecting the run of Skinty Fia singles in real time as they arrived, when the weighty, atmospheric crush of those songs wiped any reservations I still held clean off the map. There are plenty of bands nowadays, but fewer and fewer bands successfully make the jump to building an entire new world around you with each release. With Romance, Fontaines D.C. make it sound effortless.

O’Connell argues that, to a certain extent, the process has to be effortless to work at all. “I think if you anticipate creativity, you’re going against it,” he says of the album’s origins once we’ve settled on the opposite side of the patio. “The most important part is making sure that you’re constantly listening, open. If you do that, then you continue to evolve, just because you’re allowing yourself to be malleable rather than set on something. Some people live like that because it gives them a sense of safety, maybe. It’d give me a sense of despair, living like that.” He remains straight-faced and speaks evenly, almost meditative, as he leans back in his chair: “I think creativity must be unhinged.”

“Every six months, we’ll almost always have a collection of songs that could be made into an album, but it’s about whether or not there’s a heart to it—like a theme, or something that ties the whole thing together and makes it feel tangibly like one beast,” Chatten notes of Romance’s writing and recording period following the band’s stateside tour opening for Arctic Monkeys last fall. “The idea of Romance as a title was exciting to me, because it evokes the idea of a place. That was an interesting way to ground the writing process: to kind of deck the walls of this place, Romance, with these songs.”

Maybe because Skinty Fia dealt with the heft of physical location (specifically the band’s relationship with Ireland as they collectively migrated to London), Romance, by comparison, feels ephemeral—airy in even its darkest crevices, resulting in what is easily the most lush, expansive work Fontaines D.C. have produced to date. Coming to grips with what Robert Smith called “living at the edge of the world,” Romance speaks in apocalyptic terms, choosing panic as the first emotion it aims to weaponize.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-