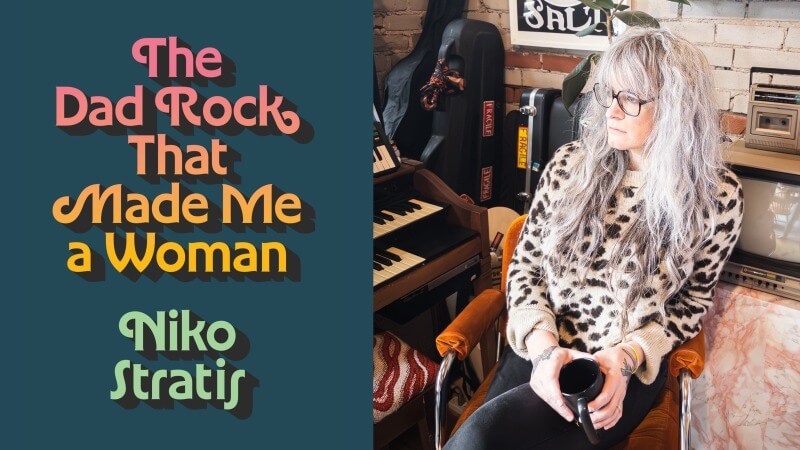

In her new book The Dad Rock That Made Me a Woman, Niko Stratis uses 20 songs to map the long, winding process of transformation. With staples like Bruce Springsteen, Fleetwood Mac, and Wilco alongside more left-field choices like HAIM, Radiohead, and Sheryl Crow, Stratis builds a canon of Dad Rock that feels personal, expansive, and quietly subversive—a Dad Rock that isn’t bound by gender or genre. The book reads as part memoir, part playlist, part musical history; a reflection on how music can hold memories even when they begin to fade.

Growing up isolated in the Yukon, Stratis turned to music as a way to access parts of herself that didn’t have a name. Writing the book meant returning to the albums that got her through, questioning the stories she’d told herself, and tracing how her evolution mirrors those of the artists she sought comfort in. What emerges is an intricate look at gender, identity, and growing up, shaped by what gets lost to time just as much as what remains. We caught up with Niko in the weeks following her book release to discuss imperfect memory, how song meanings change over time, and connecting to past versions of yourself. You can also read some of her very good Paste columns here, here, and here. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Paste Magazine: Pretty early on in the book, you write, “I’ll never remember everything perfectly as it was. It no longer matters how perfect the memory, it’s the impact.” Was that a realization that you had to come to? How did you make peace with that?

Niko Stratis: Ultimately, I’m never going to fully know the past. I’m in my forties now, so some of those years are so far in the rearview that it’s hard to see them perfectly anymore, and that has to be okay. But part of the reason why I use music so often is that it is this conduit through which I can still access former lives. There were a lot of moments that I wanted to put in the book, and I wasn’t sure I could draw them clearly enough, or that I could trust the memory of them. So I had to choose which memories belong to me and which I think are real, but I no longer trust. And that is a hard reckoning as you get older, of “What are the stories I’ve told myself are true, and what are the stories I actually believe are true?”

Did you keep a journal growing up? Or did you start the book from scratch?

I wish there had been a journal of some kind. I outlined the book when I first pitched it, so I had this rough guide. It allowed me to challenge my perception of the past in this really interesting way that was sometimes good, sometimes bad. And if there’s ever been a case for journaling more in your youth, it’s trying to write a book about yourself in your forties and being like, “So, what happened?”

I really enjoyed the way that you wrote about the Yukon and how it changed from your home to where you’re from. Did your view on it change at all while working on the book?

When I tell people that I’m from the Yukon, they have a very specific mental image. They think of a cartoon lumberjack guy with a big beard and a hat. I knew a lot of guys like that. And before I transitioned, I looked kind of like a guy like that at times. But it’s so much more than that, in good and bad ways. I had a lot of intense and formative moments there, and I’m very protective of those things. In a way that I’m protective of the box that an old TV came in. I’m like, “No, no, no, you can’t throw that out. That still means something to me.” I was hurt by growing up there in a lot of ways, but I think I was also built up in ways I didn’t see until I started working on the book. So much of the book has been me being able to find some grace for the past that I can’t change anymore.

I was thinking about this while reading the Fleetwood Mac chapter, how they existed in so many variants before they became what people know them to be now, to the point where people forget where they started. And then thinking about that idea of transformation and evolution in terms of you reaching a certain point in your gender and being like, “Okay, this is me. Everything else was me figuring it out.” I don’t know if that was something you thought of, or if it’s trite to think of it like that.

Not trite at all to think of it like that. To be honest, until you said that, I’m not sure I was ever fully consciously thinking of it that way. Because you’re right, I think a lot of people think of them as a band that started with Rumours, when it’s their [11th] record. When I was in my thirties, I thought, “I’m too old to tell people who I really am. The time to declare ‘This is who I am’ is over.” And it wasn’t until I had nothing left to lose that I decided to do that. It’s this idea of, maybe it isn’t too late to declare this is who I want to be, and this is the voice I want to have, and this is how I want to exist and be seen and be perceived. And in this era, Fleetwood Mac is becoming the band that will define them more than their past. They’re being defined by them loudly declaring, “This is who we want to be and who we want to be is messy and imperfect and fucked up, but also beautiful in its own way.”

The Replacements chapter was especially moving, seeing a coworker who abused their power over you recommending their music. Then you’re like, “Oh, but I found this song [‘Androgynous’] where they’re exploring things you’ve made it clear you’re against.” It felt very incompatible, and it was interesting to me, especially when you get into ideas of hiding things within ourselves.

There’s tension in a lot of that. It does feel a bit fraught at times. That’s part of looking back. There’s so much visible danger there that you don’t see until you’re looking at it from a distance. But so much of the stuff that was hidden away is ultimately the stuff that saved my life. And the Replacements are a band that I had a rocky start with. It took me finding them again on my own terms that they started to mean something to me. There are multiple ways you can like the Replacements. You can love the disaster of them, or you can love that something like “Androgynous,” which is from the ‘80s, is talking about something we’re still talking about now: Kids are going to approach gender and sexuality in a different way. I think Paul Westerberg and Bob and Tommy Stinson were trying to think of these outlandish and out-there ideas to challenge themselves, while also pretending to be these broke-down, drunk punks. And it’s where I was, too: pretending you’re this other person, so people don’t see the heart that’s there. But sometimes it gets through regardless.

I wanted to talk about Michael Stipe and Kurt Cobain’s influence on you. There’s also, I don’t know how what corner of the internet you’re on, but that whole “Kurt Cobain was trans—”

Oh yeah, I’ve seen that.

Yeah. I’m interested to hear about your affinity for Kurt, and how that brought you to R.E.M.

I was such a perfect age to be a Cobain fan. I was such a Nirvana-head. I used to have this column in Catapult called “Everyone is Gay,” which is a nod to Nirvana, too. And I wrote about Kurt in this way of it’s less important to me whether he was secretly trans or not, because that’s an unanswerable question. It’s more the idea of what he represented. Here was grunge, which was hot on the scene—this new, aggressive, masculine thing that’s coming out of hair metal and this glammy but misogynistic idea. And here’s this person who’s doing things that were present in glam: He’s painting his nails, wearing silk shirts, dressing in women’s clothes on stage. But he’s not doing it in a way that feels like mocking or feels misogynistic. It feels like he’s trying to open doors and windows and let the air in and see what might change if we let it. It’s a challenge to both himself and to the audience and listeners to rethink their perceptions of gender, masculinity, aggression.

And he was obviously a massive R.E.M. supporter himself.

I didn’t have cable or any good radio, so I would just steal copies of Spin and Rolling Stone and read every Cobain interview. And I knew he really liked R.E.M., and because he really liked R.E.M., I really liked R.E.M. Through R.E.M., I would try to be like, “Well, why were they so important to him?” And then I’d start looking into it and reading about it. And the more I learned about Michael Stipe—he’s such a beautiful, fascinating person. He’s fighting for HIV and AIDS awareness. When I was younger, everybody was like, “Well, he’s gay.” And in my heart I would be like, “Fucking cool, score.”

I’m still mourning the Stipe/Cobain collab we never got. Thinking about today’s masculinity, the Andrew Tates and the podcasters and all of that, where do you think you would’ve found solace if you were a teen in the 2010s?

So hard to know. In a lot of ways, I’m very fortunate to have grown up before the internet was really usable. It was just before the Bush era, and most popular media were leaning towards a punk rock political way. When you live in an isolated, remote place, all you get is popular media. You don’t get underground shit. Now, I hope that I’d be able to avoid a lot of that weird, alt-right shit. There’s an economy of rage now where it’s so easy to fan these fearful flames that thrive in people’s hearts. But I was always drawn to stuff that felt more left-leaning. I think, because I also had very progressive parents who were the classic “If you’re drinking or doing drugs, just let us know, so we know that you’re being safe,” they were there to help guide me without ever trying to force me to be any specific person. That helped, too. That’s an interesting question. I’ll be thinking about that a lot at night. Luckily, I sort of knew that I wasn’t supposed to be a man from a very young age, so I always liked masculinity if it was hinting at something else.

Yeah, like subverting a little bit. I liked the chapter about the National, where you qualify them as Dad Rock in terms of the emotional weight, and what it means to not be young anymore. I’m curious how you internalize aging and time passing, in terms of both the evolution you went through while fully coming into your gender, but also, at the same time, just going through the natural progression of life.

So of all of the essays, I was the youngest I would be writing the whole book while writing that one. And it’s interesting to reevaluate your relationship to so many of these things as you get older. I appreciate that a lot more bands that I like are growing up, but they’re challenging this idea of who they are as they grow up. When I was young, I thought I would be into punk rock forever, and now sometimes I’m like, “I’m just going to listen to jazz today,” or funk from ‘70s Japan. I used to listen to the National all the time, and I listened to High Violet, which is my favorite record of theirs, on a walk with my dog recently. It was rainy and cold and I was like, “Man, at night, when it’s shitty outside, there’s fucking nothing better than listening to a real sad National record.” And I’m glad that I can still feel that as I get older. I don’t want to lose myself.

I’m always thinking about how closely songs can be linked to memories. The immediate transportation that can happen is really interesting to me, just how powerful that is.

Now I want to ask you a question: Do you have a song that you’ve listened to recently that has brought you back to this younger age? Do you have something in regular rotation that allows you to access a younger version of yourself?

I listened to Ctrl by SZA for the first time in a while, and that came out when I graduated high school. I was just like, “Oh, I feel like a teenager now.” Kind of like how when you go back home, you revert to your teenage self. It felt very much like that.

Do you feel free even just listening to SZA? Like, “Okay, for this brief period, I can allow myself to access a younger version of my feelings that aren’t real or the same anymore.”

Yeah, it’s comforting to be like, “Wow, I had all these different things going on in my head at that time.” It’s nice to be able to zoom out to the point of “She was stressing out for no reason, or the things she was crying about didn’t actually matter.” But the music still matters.

You can be proud of that. You can be proud of the young version of yourself for getting here. A big part of it is accessing younger versions of yourself through music, through art. Part of it, too, is that a lot of it felt hard for me when I was younger. It felt hard and shitty and challenging and I wanted to die more often than I didn’t, but I still made it. But I’m able to be proud of the young version of myself for getting through, even if it was just because I chose to go home instead of going out drinking all night. I would go home and put these songs on and drain another pack of AA batteries in my bedroom. [These songs are] important to me because they’re important to the young version of myself. It’s all this weird, long journey that takes you places you’ll never expect. And accessing those old memories is just such a nice way to put the past to bed in a way where you’ve made peace with yourself.

Order your copy of The Dad Rock That Made Me a Woman from the University of Texas Press here.