Fight Night: They Live’s Endless Fistfight Is a Slapstick Masterpiece

Conflict is the most basic building block of story, and a fight is the most simple conflict there is: Two people come to blows, and one must triumph over the other. Fight Night is a regular column in which Ken Lowe revisits some of cinema history’s most momentous, spectacular, and inventive fight scenes, from the brutally simple to the devilishly intricate. Check back here for more entries.

Fight Night has been about technical proficiency, about next-level showmanship, or about the introduction of larger-than-life martial arts stars in genre-defining works. These are the fights that push cinema forward and rewrite the rules—the fascinating bouts that epitomize action movies.

And then you have fights that are just unique, out-there … maybe even silly. And I will be honest: Those are among my favorite. So of course, I am interested in one of the longest and most absurd of fights.

John Carpenter’s They Live is all sorts of things—a rant about a country slipping into greed and consumerism, an indictment of police complicity with capital, a screed that seems uncomfortably close to how some of the most odious conspiracists now view the world. It may or not be the movie with the longest fight scene—some attribute this to the John Wayne flick The Quiet Man. As it turns out, Carpenter specifically set out to eclipse that scene, according to one of the onscreen combatants, WWE wrestler and actor “Rowdy” Roddy Piper. Something like the length of a fight scene is debatable—when are you starting the clock? We talkin’ one-on-one only, or does most of the back half of The Two Towers count?

They Live may or may not have what is technically the longest fight scene. But it definitely has the fight scene which feels the longest, in the best and most gonzo kind of way. In a movie that’s already a memorable highlight in Carpenter’s filmography, it’s a completely random mark of distinction. Carpenter is truly incapable of delivering a boring experience.

The Film

It is a dark and fallen post-apocalyptic time in the United States—by which I mean it is the 1980s. A drifter (Roddy Piper) enters a rainswept L.A. and trudges to the unemployment office, where he is rejected. The movie declines ever to name Piper’s character—he is simply “Nada” in the credits. Nada falls in at a construction site with coworker Frank (Keith David) and takes up at a homeless encampment alongside an A.M.E. church. Nada and Frank are living on the margins—Frank is working cross-country from him family, and Nada’s dispossession comes after he was laid off elsewhere.

But something about the world, and the church, is off. Guerilla broadcasts are interrupting the news to shout at people to wake up and throw off their oppressors. Nada discovers that these broadcasts are coming from inside the church, which is just a front for an underground revolution. Just as he discovers this and makes off with a big blocky pair of shades that were packed up in boxes inside the church, the cops come by to slaughter or arrest absolutely everyone in the encampment. Nada escapes, and then dons the shades. These glasses defeat some kind of interference signal being sent out by the real bad guys: Gross-looking aliens masquerading as humans.

The real world is thick with their subliminal messaging. Billboards contain messages like OBEY and CONSUME, and dollar bills have THIS IS YOUR GOD printed on them. Nada loses his mind and starts striking back at these aliens, eventually seeking out other members of the underground resistance and taking the fight to Them.

It is going to sound like some kind of backhanded praise when I say that Roddy Piper’s professional wrestling career prepared him so ably for this role, but I mean it in earnest. This is the kind of movie that benefits immensely from having a lead who knows how to play to the cheap seats. He sells every stunt, every face he pulls, and every single one-liner he delivers. And on this latter point, They Live is a treasure trove: “I have come here to chew bubblegum and kick ass, and I’m all out of bubblegum.” “Life’s a bitch, and she’s back in heat.” “You know, you look like your head fell in the cheese dip back in 1957.”

But, he’s also the perfect guy for the part because if there’s one thing a pro wrestler knows, it’s how to plan and then sell a fight. All of the fights in Fight Night so far have been the climax of their respective films. Just as with its length, this fight is another exception: It happens right in the middle of the movie, as a sort of end to the second act.

The Fight

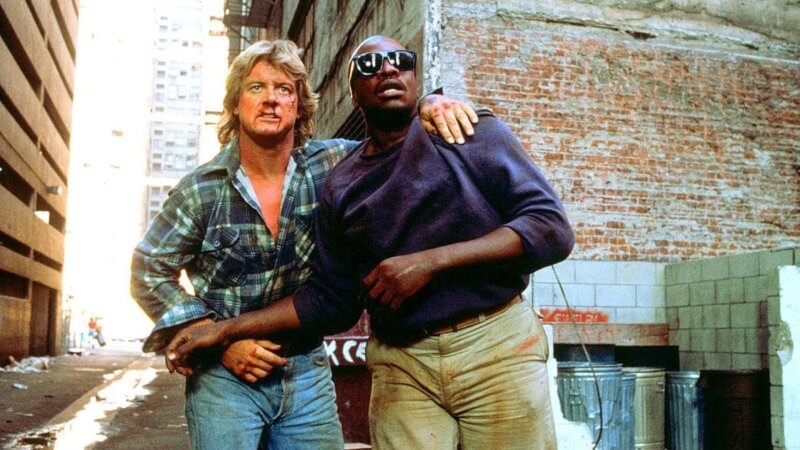

Nada and Frank encounter one another in a back alley. Nada has just finished digging another pair of the sunglasses out of the trash, and he’s determined to ensure Frank puts them on and sees the truth about Them. But Frank won’t do it. The two men have reached an impasse that can only be settled by a fistfight. Most affairs like this are a quick exchange—they rumble each other’s skulls a couple times, one of them comes out on top, and then the film moves on. “They had a disagreement and fought,” is what the bullet point might read in a summary of the script.

That is definitely what happens here. It starts happening, seems to have come to its conclusion … and then just keeps happening, for several beats too long. Nada has been convincingly laid out. Frank reaches down, appearing to help him up—only to pound him into the ground again. He then goes to continue beating down on Nada, who tries for a nut shot: “You dirty m***********!” is Frank’s response to this, a line delivery from David that gets me each and every time.

I have resisted describing fights in this column blow for blow, but here I feel like it needs to be emphasized just how many exchanges Piper and David have, and how much sillier they start to feel: Nada knocks Frank over, hauls him to his feet, and again demands he put the sunglasses on. Frank goes to crush them, and Nada starts pounding on him again to stop him, leading the two men into another extended bout. It takes them to the ground, where they wrestle and strangle and kick each other some more. Nada grabs a length of wood and starts swinging it around, bashing in the window of a car by accident—this freaks Nada out and has him apologizing…until Frank shatters the bottle he’s just grabbed. But the bottle shatters so completely he can’t use it as a weapon anymore. Keith David drops one of the all-time F-bombs of his career, and Piper just cracks up at this before the two start wailing on each other anew, during which David just lifts Piper up off the ground and throws him down.

It keeps going after this for about two more minutes. There is absolutely no reason for it. It is insane.

Eventually, Nada comes out on top, and Frank wears the glasses. A moment that could have lasted 15 seconds has dragged out to six minutes, and rather than leaving the viewer bored, by the end it leaves them laughing at the absurdity of the situation.

In a 2012 interview, Roddy Piper had much praise for his opponent in the movie, calling Keith David a “220-pound dancer” and “like Mike Tyson and [he] doesn’t know it.”

The fight ultimately lasts between 6 and 7 minutes, give or take, and is actually shorter by half than what the actors shot. Piper put his wrestling experience to use, helping Carpenter design the fight choreography and giving Keith David a crash course in stage combat. They rehearsed in Carpenter’s back yard at one point.

The Fallout

“There was a great deal of obsession with greed and making a lot of money, and some of the values I had grown up with had been pushed aside. So, I decided to scream out into the middle of the night and make a statement about that, and They Live is partially a political statement and partially a statement on the world we live in today. Right now, it’s even more true than it was then,” Carpenter said in one interview.

They Live tidily overperformed its modest budget at the box office and wormed its way into the brains of many other enfants terrible besides. The creators of painfully ’90s video game protagonist Duke Nukem gave their ripped, blond muscle man a bunch of cold one-liners that are yanked straight from They Live and the Evil Dead series—Duke also wears big blocky shades. At one point, South Park staged a beat-for-beat homage/parody of the long fight, choosing for their combatants two characters with physical disabilities, Jimmy and Timmy. In an interview, Piper said this actually didn’t sit well with him, but softened some years later while he was out signing autographs and a kid in a wheelchair approached, “laughing his off” with excitement about having Piper sign something precisely because he was a fan of the South Park and by extension the They Live fight.

It’s impossible not to talk about the uncomfortable aspects of the story. Conspiracism in the United States is as bad as it has ever been, and any time you wander into the comments section of a video clip of this movie, you’ll have people quoting The Matrix or otherwise showing their asses. The fine and upstanding citizens who regard every person with a skin tone darker than paste as invaders, or who see secret pedophilia operations in the basement of random pizza parlors, probably see themselves as a great deal like Nada.

I don’t think this was intentional on Carpenter’s part, though, because he’s pointing it specifically at Reagan-era America’s worst excesses—simply put, the side of the political spectrum peopled with most of America’s conspiracist cranks. This is a movie that is hard to misinterpret. The rich are so rich that they may as well be aliens, and their wealth allows them to control everything. In a time when the presidency just got bought by some South African trillionaire dope who has utterly reordered the entire federal apparatus, it is hard to dispute Carpenter’s premise.

And it really puts that fight into context. Nada just needs Frank to accept who the enemy is, to awaken—to enter a state of wakefulness. To become “woke,” if you will. And Frank, a working man who just wants to make his dime and look the other way, won’t do it. Will, in fact, fight tooth and nail for six onscreen minutes not to do it. The fact this movie’s perspective sounds like that of a ranting crank with the lowest possible opinion of humanity—exactly the sort of person ready to believe Q-Anon craziness, 9/11 trutherism, or vile antisemitic garbage—is unavoidable.

But it’s also how I feel when I am over here trying to explain to people that my trans daughter just wants to graduate college and play video games without ending up in the second act of V for Vendetta. This is all I’m saying, folks.

Kenneth Lowe is a regular contributor to Paste Magazine. You can follow him on Bluesky @illusiveken.bsky.social. To support his fiction, join his Patreon.