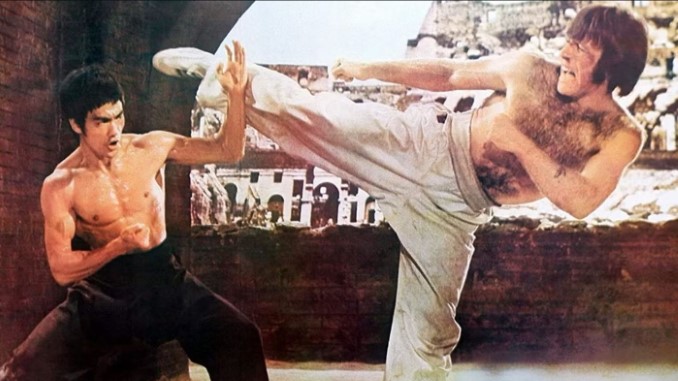

Fight Night: Bruce Lee vs. Chuck Norris in The Way of the Dragon

The Colosseum fight was a swan song for Lee in the States, and Norris’ debut

Conflict is the most basic building block of story, and a fight is the most simple conflict there is: Two people come to blows, and one must triumph over the other. Fight Night is a regular column in which Ken Lowe revisits some of cinema history’s most momentous, spectacular, and inventive fight scenes, from the brutally simple to the devilishly intricate. Check back here for more entries.

Be formless. Shapeless. Like water. You put water in a cup, it becomes the cup, you put water into a bottle, it becomes the bottle, you put it into a teapot, it becomes the teapot. Now, water can flow, or it can crash. Be water, my friend. — Bruce Lee, on the Pierre Berton Show in 1971

When Chuck Norris falls in water, Chuck Norris doesn’t get wet. Water gets Chuck Norris. — Oft-repeated “Chuck Norris joke,” ca. 2004.

I’ve written about how Bruce Lee’s cultural legacy—and specifically the palpable agony people still feel over his premature death more than 50 years ago—looms large over Hollywood and Hong Kong. It is difficult to imagine martial arts movies, television, or even entire broad genres of videogames, without Lee’s influence. In Fight Night, I hope to dig into the movie fight scenes that truly define the art form. In the case of the showstopper at the end of Lee’s directorial debut—and the last of his films released while he was still alive—the fight scene in question goes beyond just cinema.

Part of the reason why is Lee’s opponent—a tall, ruggedly handsome (if profoundly hirsute) fellow competitive martial artist named Carlos Ray “Chuck” Norris. Norris, already an accomplished competitive fighter in Karate, met Lee, then a co-star of The Green Hornet, and the two developed a friendship as they worked and trained together. Lee is a kung fu demigod in Hong Kong cinema history, and the subject of dorm room posters for the past half a century. Norris has largely stepped back from film and TV roles as he’s grown older, but his acting career came after learning Tang Soo Do in the military, opening a martial arts studio, and multiple Karate tournament championships.

Norris is no Lee, and never was, of course. There is a reason he’s the subject of Chuck Norris Facts—a bizarrely resilient class of internet joke from those wild and crazy ’00s: Even as he’s always being completely earnest and even as it’s apparent that he could easily kick you apart, he’s also a wooden actor who has starred in mostly low-to-mid-budget, guilty pleasure sort of stuff. It is therefore plainly funny to come up with exaggerated claims about the guy’s power. Lee, by contrast, is a Platonic ideal whose every pose, every strike, every line reading, seems calculated to flood the viewer’s brain with adrenaline. The guy needs no promoters.

Put Norris in a fight with Lee and you have something very special: Two fighters with the raw strength and instinct of martial arts tournament champions and the technical expertise of Hollywood stuntmen. These are two fellows who know how to move. It’s the recipe for the kind of spectacle that could only feel at home in the Colosseum.

The Film

Lee’s death mere weeks before the release of Enter the Dragon turned him into a star back in his native United States and set off a kind of retroactive frenzy, kicking off the dubious subgenre of “Bruceploitation” martial arts movies. But it also gave Americans a hankering for all martial arts flicks, something the 1972 movie The Way of the Dragon reinforced when it was redubbed and rereleased in America as Return of the Dragon in 1974.

The way to watch the movie, though, is to get your hands on the remastered edition (available most notably in Criterion’s collection of all of Lee’s films). With the original dialogue (and thus preserving, you know, Lee’s actual performance), The Way of the Dragon reads more clearly as Lee’s first shot at embodying his all-inclusive philosophy, with the control that comes from sitting in the director’s chair.

Like all Bruce Lee flicks, it’s a simple enough setup: A Chinese restaurant in Rome is being shaken down by the local mafia, and they send for aid in the form of Tang Lung (Lee). More fascinating than any of the fights are early scenes in which Lee’s character arrives in Rome feeling completely adrift and judged by glaring white people—another manifestation of the theme of oppression and discrimination that runs through all of Lee’s work.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-