Every John Carpenter Movie, Ranked

Of all the superlatives one can lay at the feet of director John Carpenter, the thing that always sticks in my mind is the fact that Carpenter managed to end up with a phrase as broad as “the master of horror” indelibly associated with him. That is a really general statement, and yet horror film geeks know exactly who you’re talking about when the phrase “the master of horror” is mentioned in a ranking or conversation. And it’s not George Romero, or Mario Bava. It’s not Tobe Hooper, or Wes Craven, or even the likes of James Wan. No, it’s John Carpenter—it’s even the guy’s Twitter handle! Talk about effective marketing, right?

And it’s funny, looking back at Carpenter’s generous feature film career, because although there’s obviously plenty of classic horror cinema represented, the director’s talents have actually been spread through quite a few genres over the years. Carpenter started his career in satirical science fiction comedy, in fact, before branching out into everything from crime dramas, to love stories, to martial arts action spectaculars. The horror genre may be the “home base” of Carpenter’s career, as we’re reminded with each of the endless string of modern Halloween sequels, but even the “master of horror” had a career far more eclectic than many realize.

It’s been 12 years since the master’s most recent feature film, and the last decade has seen the 74-year-old Carpenter increasingly focused on everything from musical composition and production to videogame fandom. But you always have to wonder if Carpenter believes he has one more feature left in him, and if with the closure of the original Halloween timeline in Halloween Ends, he might feel compelled to bless audiences with his cynical vision one last time. He keeps mentioning that prospective Dead Space movie, after all …

In honor of the master of horror, we recently rewatched every single theatrically released John Carpenter feature film, to assemble the following ranking. Consider it a guided tour of one of the most unique careers in Hollywood history.

Here’s every John Carpenter movie, ranked:

18. Ghosts of Mars (2001)

The absolute nadir of Carpenter’s career, this dreary amalgam of science fiction, horror and action tropes is sold by its fans—what few exist—as some kind of genre satire, but unlike Escape from L.A., it’s difficult to believe while watching that the director intended any kind of knowing parody. And even if he did, it wouldn’t excuse the film’s myriad failings, horrendous casting and depressingly shoddy production, which results in a visual style that suggests not an auteur making a subtle satire, but a tired director running out of both style and steam. It doesn’t matter how you approach Ghosts of Mars—as camp, as comedy, whatever—it’s still a slog to get through, even if it definitely will elicit the occasional guffaw of disbelief. How else could one react to a film told as one long flashback (for no narrative reason), while simultaneously containing multiple levels of flashbacks-within-flashbacks? Inception this ain’t.

Seemingly inspired by both westerns and classic zombie films, the latter of which inform many of the director’s films, Ghosts of Mars is extremely lazy and unambitious for what sounds like it would be a grand sci-fi spectacle. Almost all of the action takes place in a remote, squalid “mining outpost,” which is simply an excuse to use the same exceedingly unimpressive, generic sci-fi sets over and over again. Everything is grating, from the absurd costumes, to the crunching and out-of-place rock soundtrack, to the jaw-droppingly bad CGI action, to the committedly skeevy characterization of Jason Statham’s Sergeant Jericho. Opposing the ragtag band of Mars soldiers, meanwhile, we have a “villain” who speaks entirely in gibberish, and is never even given the courtesy of a name. In the end credits, he is dubbed “Big Daddy Mars.” Sounds like a compelling antagonist!

All of the worst traits and fascinations of late-career Carpenter are at their most deleterious in Ghosts of Mars, from the constant barrage of sexist characters, to his utter fixation on fades and schizophrenic editing, which first became a major problem in Vampires before reaching its zenith here. At one point, a character needs to walk from one end of a room to the other, a distance of maybe 15 feet, and Carpenter uses a fade to have them travel the distance rather than just showing it or cutting to them on the opposite side of the room. It’s sort of amazing that this was a film made at the end of Carpenter’s career, because it feels like something he might have shot when he was 13. Truly terrible, it needs to be seen only by film fans committed to critiquing every feature in the man’s career. Everyone else can safely ignore Ghosts of Mars.

17. Vampires (1998)

Vampires is considerably more technically proficient than Ghosts of Mars, but it suffers mightily in the department of characterization, while sadly also the most regressive and painfully misogynistic of all Carpenter’s features. The film makes up a little ground through some attractive cinematography, especially in its western landscapes and establishing shots, but after finishing Vampires it’s the atrocious action, embarrassing one-liners and reprehensible attitude toward women that will stick in the viewer’s mind.

In its opening moments, though, Vampires does seem to promise an action-horror allure that splits the difference between gritty and flashy. The initial sequence of vampire hunter Jack Crow (James Woods) and his crew of mercs clearing out an old farmhouse full of vampires by hooking them like fish and pulling them screaming out into the sunlight to be vaporized has a thrilling callousness to it, an attitude of almost bureaucratic professionalism applied to the battle between good and evil. The film immediately chooses to dynamite that dynamic, though, eliminating Crow’s entire crew in a motel massacre sequence that is frankly stunning in its almost total lack of coherent choreography and editing. This is the moment that Vampires sheds whatever bits might have been compelling, stranding us with both heroes and villains impossible to accept at face value. Make no mistake, this villain can speak, but in every other respect he’s just about as generic and uninteresting as “Big Daddy Mars.”

The far bigger problem, though, are characters such as Daniel Baldwin’s relentlessly pathetic and chauvinistic Tony Montoya, and Woods’ portrayal of grizzled vampire slayer Crow. In the 12 years that passed between Big Trouble in Little China and Vampires, it’s as if Carpenter is now unironically writing the very epitomes of the male jock hero he was once lampooning. Where we’re meant to understand that Big Trouble’s Jack Burton is a fool, blundering goodnaturedly into an adventure he doesn’t really understand, it feels like we’re supposed to find the character of Jack Crow cool as hell, as if Woods’ tight jeans (black tank top tucked into them) and abhorrent one-liners represent the peak of male bravura. Worse, it’s not just the characters who are constantly objectifying the few women in the film—Twin Peaks icon Sheryl Lee is done a grave disservice by the camera itself, which invites the audience eyeballs to graze on her body as she lies naked, tied to a bed by our protagonists. As a fan of Carpenter, it’s a tough film to watch, and I’m glad Vampires stands out as more of an outlier than a persistent theme in the man’s career.

16. Dark Star (1974)

Carpenter’s first feature film, Dark Star is an uneven, messy, but cinematically curious bit of ephemera, one that feels like a student art film primarily because that’s exactly how it began its life. Carpenter co-wrote with Dan O’Bannon, the writer of Alien and eventual writer-director of the immortal Return of the Living Dead, and some of O’Bannon’s wry humor can be felt in this tale of lazy, mentally addled long-haul space pilots as they suffer their way through an endless mission of destroying unnecessary or “unstable” planets. We can also palpably feel the crew’s debilitating boredom as they drift through space on a pointless quest, growing old as they listen to elevator music. It’s a slow, slow way to die.

Dark Star is at its best while exploring the philosophical confines of what feels like an experimental short film, as encapsulated by the redundancies and illogical nature of a system where the space pilots must debate with their own, A.I.-empowered and sentient bombs in order to convince the bombs to do their jobs. These strange discussions allow for rambling pontificating on the nature of free will and identity, contributing what are ultimately the signature sequences of Dark Star—men arguing with bombs about whether they should or shouldn’t explode. It’s as strange to see on screen as it sounds on the page.

Unfortunately, though, the film bogs down interminably in the second act, during a sequence involving a beachball-shaped alien creature on the loose in the ship, feeling for all intents and purposes like extra footage that was crammed into a short film to help it reach “feature length.” The end result is a film that feels stretched well past its breaking point, occasionally blessed with moments of imagination and a kooky sense of humor, but nowhere near ready to fill even 83 minutes of screentime. It absolutely feels like a first feature, albeit an admirable one.

15. The Ward (2010)

The Ward is Carpenter’s most recent feature film to date, and represented his Hollywood comeback after almost a decade, following the disaster that was Ghosts of Mars. And as a comeback, The Ward really isn’t bad—it proved he could still quite competently put a movie together, but it ultimately aspires to very little else, unless you want to give it a huge amount of credit for what turns out to be a deeply illogical twist in the final moments. It feels like a very “safe” attempt to get back on his feet, and honestly that’s fine. It’a also easy to appreciate that Carpenter thankfully dismisses the more problematic, misogynist elements of some of his later works, which is significant here given the film’s cast of young, attractive Hollywood starlets. With the One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest psych ward setting, The Ward easily could have descended into full-on “women in prison”-style exploitation, but this time around the director displays some welcome restraint in objectifying his cast.

As for the script, The Ward is for the most part a classic ghost story, fused with abusive psychological escape drama. It’s not particularly visually striking, but the worst excesses of Ghosts of Mars and its obsession with fades are toned down a bit here, and it does feature a character lineup of enjoyably kooky residents, each with their own tics, evocative of something like the mental hospital residents of A Nightmare on Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors. Getting on board with the protagonist played by Amber Heard, on the other hand, is a bit more difficult—we’re meant to empathize with her due to the mistreatment she perceives, but she’s simultaneously resistant to all genuine attempts to help her situation. How can one really be in the camp of a character delivering the line “there is no emotional trauma!” while she’s simultaneously weeping and flashing back to her memory loss from the day before? Even when she meets those genuinely attempting to help her, she shows little interest in self preservation.

And as for the big reveal … well, it’s some classic cheese, with implications that immediately introduce half a dozen paradoxes in the events we’ve already seen. At the end of the day, The Ward feels like a competent, low-budget potboiler, rather than the passionate return of an industry legend to the spotlight.

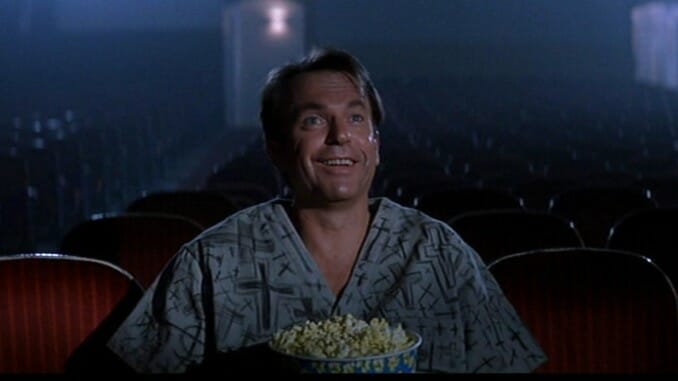

14. Memoirs of an Invisible Man (1992)

In the 1980s, John Carpenter had produced an extremely impressive string of genre classics, though not all (such as The Thing) had been received as successes at the time. The 1990s, on the other hand, saw Carpenter initially trying to expand and seemingly shed his image as exclusively a horror filmmaker, resulting in one of the strangest projects of his career: 1992’s Memoirs of an Invisible Man.

This is a film uniquely adrift in terms of its tone, constantly at odds with itself over what exactly it’s supposed to be. In the 2000 book Which Lie Did I Tell? by screenwriter William Goldman, he writes that Memoirs of an Invisible Man had originally been developed as a vehicle for Ghostbusters director Ivan Reitman, before Reitman bailed due to disagreements with notoriously difficult star Chevy Chase. It’s easy to imagine how this version of the film would have been a far more natural fit, combining some of the same smart aleck humor of Peter Venkman with a similar fusion of science fiction, comedy and even light horror. In the hands of John Carpenter, however, it feels like Memoirs of an Invisible Man is constantly being pulled in multiple ways at once. While Carpenter resists the imperative for the film to be scary or science fiction-driven, seemingly seeing it as more of a combination of drama, noir and romance, star Chevy Chase seems dead set against committing to any of the material in the script that was likely intended to be more overtly comedic.

This seeming clash between script, director and star leaves Memoirs of an Invisible Man in a strange, moribund place, stranded between distinct takes on the same material that probably could have been pulled off more effectively. The reliance on parodic, noir-style narration is an odd touch, and Chase’s Nick Halloway never quite manages to materialize into a relatable figure. The one person who does come off surprisingly well is Sam Neill as effectively dangerous-looking CIA agent David Jenkins, a performance that must have impressed Carpenter, given that he went on to cast Neill as his lead in In the Mouth of Madness two years later. Memoirs, on the other hand, has the distinction of feeling like perhaps the “least Carpenter” of any movie in the director’s filmography.

13. Escape from L.A. (1996)

It’s rare to find a film sequel that is simultaneously so similar, and so opposite its predecessor, but Escape from L.A. is that movie. Where Carpenter’s 1981 original is a brooding, moody piece of dystopian satire, one that gets by on tone and the undeniable star presence of Kurt Russell more than it does on actual action or setpieces, Escape from L.A. runs wild with every conceivable idea that passes through the head of its writer-director. Snake Plissken hasn’t changed, but the world around him has gotten orders of magnitude more absurd. What this yields is a relentlessly zany adventure, featuring a protagonist embodying the utter zenith of the badass cinematic antihero—he’s every Han Solo trope, except stretched well beyond the boundaries of any kind of reality. That character is turned loose in the least subtle social satire imaginable, and yet Escape from L.A. defies its crummy reputation by simultaneously being deliriously entertaining from start to finish. By this metric, at least, Escape from L.A. is a better film than it’s often portrayed.

As for the story, it’s literally Escape from New York all over again, as captured outlaw/legendary soldier Snake Plissken is given another suicide mission by the U.S. government, to infiltrate the penal colony of L.A. in a dystopian 2013, where all the undesirables are housed in a United States that has been overthrown by the religious far right. Kurt Russell is again the film’s biggest asset, as he oozes true movie star charisma. The fact that he manages to do that while dressed in a leather catsuit, looking like he’s holding out for the release of The Matrix in three years, is all the more impressive. There’s something gloriously stupid about the challenges he’s made to take on in this film, especially when he’s forced to dribble and shoot basketballs to save his life in the film’s crowning sequence.

Escape from L.A. is so aggressively absurd, in fact, that its proponents often claim the entire film is very much intended as parody of both American machismo and action cinema cliches. I can’t say for certain whether this is true—it certainly feels like Carpenter truly believes Snake is the coolest dude around—but whether or not the director intends it, the audience is still able to enjoy the film as parody, and it functions much better this way. The atrocious CGI, childish costuming and characters with names like “Cuervo Jones” only add to this effect, as does the absolutely breathless pace, which often sees elaborately detailed sets used for a single three minute scene before being immediately discarded. Never has it felt like Carpenter had more money to burn, and it makes perfect sense when you see that Escape from L.A. possessed the biggest budget of his career. Of all the movies in his filmography, this one feels the most deserving of the title “guilty pleasure.”

12. Village of the Damned (1995)

Although one typically thinks of John Carpenter in the context of original screenplays and story concepts, it’s not as if the guy was opposed to making a story that had been told before—The Thing is effectively a remake, after all, of Christian Nyby’s classic The Thing From Another World. But where The Thing is a clear Carpenter passion project, his 1995 remake of 1960 British horror flick Village of the Damned feels much more like cinematic mercenary work, with Carpenter basically shrugging his shoulders at subpar casting and a thoroughly conventional script, and electing to simply get the project done without investing his heart in it. Perhaps he was still disappointed at the time at the box office failure of In the Mouth of Madness a year earlier.

Regardless, this is a workmanlike effort all the way, and is arguably Carpenter’s most competently forgettable film. It benefits from the strength of its basic premise, which is as powerful and inexplicable as ever—the entire population of a town collapses one day, only to find that a handful of town women have suddenly become pregnant. When born, the silver-haired children are emotionally cold but hyper-intelligent, seeming to act as a hive organism before they start using their innate psychic powers to torture anyone who would stand in the way of their mysterious plans. The child casting is actually one of the film’s stronger aspects, and there’s some effective cinematography and imagery of the group of kids marching in lockstep, highlighting the budding humanity and individualism of David, the only one of the children without a “partner.”

Unfortunately, the film is let down by much of its starring cast, particularly Christopher Reeve as the primary protagonist. He’s still operating in full-on Superman mode, and his moralizing feels stiff, wooden and unrealistic throughout. Mark Hamill is wasted as the wild-eyed town preacher, a character that could have been utilized more heavily to illustrate the human side of evil. Likewise, the “horror” sequences of the kids using their powers to force townsfolk to destroy themselves have a tendency to come off as silly rather than scary. All in all, Village of the Damned just feels short, tidy and perfunctory—it’s perfectly watchable, but has no particular interest in exploring any ethically gray territory. Carpenter punched in, got the job done, and punched out.

11. Christine (1983)

Christine certainly doesn’t feel like one of John Carpenter’s bigger or more ambitious films, but it’s a more than competent Stephen King adaptation all the same. Tidy and self-assured, it has all the King hallmarks one expects—the psychotic high school bullies, the classic rock ‘n roll music—punched up with some fantastic (but sparingly used) practical effects and a few flourishes of classic Carpenter electronic musical scoring. It’s not quite as likely to leave a lasting impression as some of the director’s other works of the era, but it’s a very easy watch.

Our characters in Christine are essentially a menagerie of greasy, surly high school weirdos, with the nebbish Arnie as our unlikely leading man. To the very last person, everyone on screen in Christine is terminally horny—even the old man who sells them the car—and their conversational patter abounds with what can only be described as raunchy “locker room talk.” Perhaps it’s this overall attitude that is to blame for everyone seemingly not noticing when Arnie acquires the junker of a car and begins to undergo radical personality changes.

What follows is a story about temptation and empowerment, and Arnie does become effectively creepy as Christine comes to dominate his psyche. There are some excellent conversational scenes featuring Arnie and his friends, cruising the interstate late at night, which illustrate the dangerous fatalism he’s acquired from his prized possession Christine. In the end, it’s a sick little love story, but not between man and woman.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-